I went to the windowpane and pressed the paper against it. I had to focus, but then I began to see them: translucent white lines, surfacing like ghosts between the inked ones.

There was another letter, hidden within the letter.

I squinted. “I can’t make it out. The words are too faded.”

“The special ink he used is activated by lemon juice,” Cecil explained. “It’s a familiar ploy, and I’m ashamed to admit it took me a while to figure it out. Clearly this is not the work of a trained spy. At first, I thought someone was playing a trick on me, in rather poor taste, sending me reports of seemingly innocuous events at court. But as they kept arriving, I started to get suspicious. Fortunately, Lady Mildred always keeps on hand the juice of preserved lemons from our orchard.” He met my stare. “I have transcribed everything for you here, on this paper. What that invisible letter says is that unofficially, the Spanish delegation brought Charles V’s secret offer of marriage to his son, Prince Philip.”

“Philip?” I started. “As in, the prince of Spain?”

“The same. And the emperor is more than a fellow sovereign: He is the queen’s first cousin, whom she’s always treated as a family confidant. She relies on his advice. Should she accept his offer of marriage to his son, one of the terms of the betrothal will be returning England to the Catholic faith. Charles V will tolerate nothing less. It also goes without saying that a rapprochement with Rome would be calamitous for every Protestant in this realm, and most of all for Elizabeth.”

He picked up the page on which he’d transcribed the invisible words from the reports. “See here. ‘Her Majesty heeds exclusively the imperial ambassador, Simon Renard, who deems Elizabeth a bastard and heretic, and menace to the queen.’” He glanced up at me. “They’re all in this vein: two or three secret lines per report, yet taken together they present an undeniable picture.”

My heart started to pound. Cecil might be a liar, but when it came to Elizabeth he was nothing if not thorough. She meant everything to him; she was the reason he persisted, the beacon that guided him through the shoals of his disgrace, as the fall of Northumberland had been his fall as well, for Queen Mary had exiled him from court.

“Her Majesty doesn’t strike me as someone who is easily swayed by others,” I said.

“Yes, she is like her father that way; she makes up her own mind. But she is also the daughter of Catherine of Aragon, a princess of Spain, and Simon Renard represents Spanish interests. He has served the Hapsburg emperor Charles V for many years, and she takes his advice seriously. If Renard is advising that Elizabeth poses a threat to her faith and her desire for a Hapsburg marriage, nothing could be more calculated to rouse her suspicions. After all, religion is the queen’s lodestone. She believes God himself guided her through her vicissitudes to the throne. Elizabeth is a Protestant; she stands in direct opposition to everything Mary hopes to achieve, including returning England to the Catholic fold.”

Alarm went through me. “Are you saying this man Renard seeks the princess’s arrest?”

“And her death,” replied Cecil. “It can mean nothing else. With Elizabeth out of the way, the succession is to Prince Philip and Mary’s future child. An heir of Hapsburg blood to rule England and unite us with the empire, thereby encircling the French-it is Charles V’s dream. Renard is a career civil servant; he knows whoever delivers that dream stands to gain a great deal.”

I stared at him, aghast. “But the queen would not harm her. Elizabeth is her sister and…” My protest faded as I took in Cecil’s expression. “Dear God, do you think he has any proof against her?”

“Besides accusations whispered in the queen’s ear? No, not yet. But that doesn’t mean he shan’t be long in obtaining it. Make no mistake: Simon Renard is a tenacious opponent. When he sets his mind to something, he will not stop until he achieves it.”

I clearly heard the soughing of the evening wind rising outside. I took a moment to collect my thoughts before I said quietly, “What is it you want from me?”

He smiled. “What else? I want you to go to court and stop Renard. You earned Queen Mary’s trust when you risked yourself to help her escape Northumberland’s coup. She would welcome you. Gain a post in her service and you can beat Renard at his own game.”

I let out a terse laugh. “Just like that? I return to court and the queen grants me hearth and board, and a post to boot?” My mirth faded. “Do you think me a complete fool?”

“On the contrary, I think you have a flair for this work, as previous events have shown.” He glanced at the pile of books by his side, now overlaid by his reports. “I do not believe this rural life can satisfy you for long, not with so much important work yet to do.”

His unexpected insight stung me, more than I cared to admit. I didn’t relish his knowing things he had no right to. I didn’t want him inside my head.

“The last time I accepted an assignment from you,” I said, “I almost perished.”

“Yes.” Cecil met my regard. “A spy does run that risk. But you prevailed, and rather well, I might add, all things considered. This time, at least you’ll be prepared and know who your foe is. You will also return to court under the alias I gave you when you first met Mary. You will be Daniel Beecham, and his return is unlikely to arouse much interest.”

He rose from the window seat, leaving the reports on my books. “You needn’t answer me now. Read the reports and consider whether you can afford to ignore them.”

I didn’t want to read his reports. I didn’t want to care. Nonetheless, he had already lured me to his bait. He stirred something in me that I could not evade-a restlessness that had plagued me ever since I had left court for this safe haven.

Cecil knew it. He knew this terrible craving in me because he also felt it.

“I still must talk to Kate about this-” I started to say. I stopped, noting his impatient frown. “She already knows, doesn’t she? She knows you want to send me back to court.”

“She’s no fool, and she cares for you-rather deeply, it would seem. But she also understands that in matters such as these, time is often the one commodity we lack.”

I clenched my jaw. I thought of Kate’s enthusiastic cajoling of me to master the sword, her determination for me to excel. She must have suspected a day would come when I’d be compelled to return to court in defense of Elizabeth.

“I should wash up before supper,” said Cecil. “I assume you’ll have more questions after you read these. I can stay the night, but tomorrow I must return to my manor.”

“I haven’t said I agree to anything.”

“No, not yet,” he replied. “But you will.”

Chapter Two

Outside the window the gray sky leached into the colorless winter landscape, blurring the demarcation between air and land. Gazing toward the forest, where bare trees swayed in the snow-flecked wind, I felt this haven, this place of refuge for me, begin to fade away inexorably, like a brief, idyllic dream.

We can guide her to her destiny-you and I. But first, we must keep her alive …

I turned to the window seat and took up the reports. There were six total, and though I pressed each one to the glass, in the ebbing afternoon light it was difficult-impossible, in some cases-to decipher everything written between the inked lines. Cecil’s concise transcription, however, confirmed what he’d told me: It appeared the Spanish ambassador Simon Renard had sowed fear in the queen regarding Elizabeth’s ultimate loyalty to her, using the princess’s Protestant faith to tarnish her reputation and implicate her in something dangerous enough to warrant her arrest. What that something was, the informant did not say, probably because he didn’t know. There were various mentions of one Edward Courtenay, Earl of Devon, a nobleman who apparently had befriended the princess. I made a mental note to ask Cecil about this Courtenay.

I didn’t realize how long I’d been sitting there, reading, until I heard Kate’s footsteps on the creaking floor. I looked up to find the gallery submerged in dusk. She stood before me in a sedate blue gown. As she took in the papers strewn about me, she said quietly, “Supper is almost ready.”

“You knew about this,” I said.

She sighed. “Yes. Cecil wrote to say he had urgent news concerning Her Grace; he didn’t give any details, just insisted he must speak with you. What was I supposed to do?”

“You could have told me.”

“I wanted to, but he said he wanted to show you something in person.” She glanced again at the papers on the window seat. “It looks serious.”

“It is.” I told her about the reports and what Cecil had extrapolated from them.

When I finished, she wet her lips. “God save us, danger follows her like a curse.” She exhaled a worried breath. “I’ve been dreading this day, hoping against hope it wouldn’t come to pass.”

I stood and took her hands in mine. She had strong hands, bronzed from working on her treasured herb garden, her nails cut short, with a hint of dirt under them. All of a sudden I ached at the thought of leaving her.

“If these reports are true, she needs me,” I said. “What I don’t understand is why she hasn’t written to us directly. Surely she must know by now that she is in danger.”

“If she does, it’s not a surprise that she hasn’t written,” Kate said. I looked at her, frowning. “There was a time before I served her,” Kate added, “when she was sixteen years old. She became implicated in a treasonous plot hatched by her brother Edward’s uncle, Admiral Seymour, who was beheaded for it. Elizabeth was harshly questioned, our own Mistress Ashley taken to the Tower for a time. When Elizabeth told me about it, she said it was the most frightening time of her life. She vowed she’d never willingly put a servant of hers in danger again. She hasn’t written because she’s trying to protect you. You must think me very selfish for wanting to do the same.”

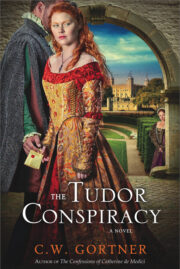

"The Tudor Conspiracy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Tudor Conspiracy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Tudor Conspiracy" друзьям в соцсетях.