I looked down at my boots. Taking my knife, I lightly scored the soles and took up handfuls of snow, rubbing them into the grooves. It might help stop me from slipping.

I sidled out onto the frosted edge. Fear cut off my breath. I told myself to focus, take slow steps, one foot in front of the next, as if I moved across a newly polished floor. As I progressed, the city disappeared behind me in the mist, but the noise of the south bank ahead did not yet intrude. The clouds parted for a glimpse of the moon; her silver halo dazzled, scattering diamond fragments across the river. With the black sky above me, embroidered with a thousand brilliant stars, and the Thames like a fantastical sea, bewitched in midmotion, I came to a halt. It struck me how cruel the world was; even as a child died in agony, nature could clothe herself with such majestic indifference.

Then I moved forward again, almost losing my balance, slipping and scrambling toward the shore. The cold I’d ceased to feel only moments earlier returned with vicious suddenness. I drew the hood of my cloak further over my head, my feet like blocks of ice in my boots as I clambered up the Southwark bank.

Sidestepping discarded drift nets, I stared at an odd tableau ahead: fire pits tossing sizzling embers into the air and the smell of bacon thick. I could see crowds; as I approached, to my amazement a night fair burgeoned before me.

Divided by meandering narrow dirt lanes were tables under sagging tarps held up by ropes, laden with piles of tarnished platters, pyramids of goblets, threadbare carpets, faded tapestries, splintered knives, and old cloths. In the tarry light of the fire pits, street vendors and alewives circulated offering meat pies, pastries, and other foods while crowds mingled-mostly men, from what I could discern under their layers of clothing, but also some women, bold and strutting, all perusing the displays. The vendors hawked their wares with tireless enthusiasm, though in subdued tones more suited to a graveyard than a market site. It seemed no one wanted to alert the authorities.

I was careful to not draw attention, keeping my head lowered as I blended with the crowd. At first I mistook the jumbled silver pieces on a nearby stall for looted goods, though it struck me that surely such wealth could not have gone unreported, much less unconfiscated. Then I saw an upholstered prayer bench, complete with gilded angels on its carved frontispiece and worn velvet cushion for the knees. I paused. Beside it were heaps of torn book clasps, many of which had chipped enamel iconography, and a wood trough such as pigs might use, filled to the rim with coiled rosaries.

The fair was selling rapine from the monasteries.

The stall owner lumbered up to me-a potbellied, bearded man with pitted skin. He babbled at me in an incomprehensible language; it wasn’t until he was jabbing his finger at my chest and repeating his words that I suddenly understood he spoke English.

“Buy or go,” he said. “You no look here.”

For a moment, I couldn’t move. As I met the man’s yellowed eyes I had an unbidden recollection of a time now gone, a time I had never witnessed but had only heard about, when these holy refuges for the sick, weary, and poor once dominated the realm, until they fell prey to King Henry and his break with Rome.

I felt a sudden rush of heat, a searing desire to grab this man by the scruff of his jerkin and remind him that what he so callously sold as scrap had once been revered by hundreds of monks and nuns, who’d been turned out of their ancestral homes. I knew in some remote part of me that it was my grief and I mustn’t let it get the better of me. I could not indulge a meaningless altercation now, not when my real target lay ahead. Yet even as I fought to stay focused, I wrestled with my compassion for the queen. Mary had clung to her faith against all odds, unaware that what she sought to salvage had already been forsaken.

The man’s hand dropped to his belt. Before he could draw his weapon, I strode off, leaving the fair behind for the rows of hovels clustered together like moldering mushrooms. The barking of dogs and agonized roar of a bear being taunted in a pit curdled the chill; on the thresholds I now passed lurked figures in tattered gowns, some no older than girls, their gaunt faces painted in a mockery of enticement. A lewd invitation floated to me, a cocked bony hip and beckoning finger …

I had reached the whorehouses.

I came to a halt, uncertain of which way to turn. In the night it all looked the same-filthy, decrepit, and corroded by suffering. The visceral pain of Peregrine’s death collided with my understanding of the damage Renard brewed with Mary’s marriage, which would pit her in a battle against her Protestant subjects, and all of a sudden I wanted this errand done with. I wanted to fulfill my mission and get as far from the court and London as I could.

When I finally espied Dead Man’s Lane, I kept to pockets of shadows, my senses attuned. The Hawk’s Nest came into view, a far different building from its daytime incarnation-the shutters of the upper story pulled back, candlelight winking in the mullioned glass, the faint sounds of music and laughter drifting on the cold air.

The front door opened. Two men staggered out, silhouetted by the light spilling from inside. I could see at least one of them wasn’t from the neighborhood. He was tall and well built, with a fur-trimmed mantle tossed across his shoulders: a courtier by the looks of it, and of evident means. His companion was slender, smaller. As they careened down the alley where I lurked, the boy let out a lascivious giggle.

I palmed my blade. They came closer, tripping over each other and laughing. I could smell the alcohol wafting off them from where I hid in a doorway. All of a sudden, the boy yelped as the courtier swung him to the wall and began groping him with drunken urgency, the boy emitting squeaks of feigned protest.

I pounced.

The courtier froze when he felt my blade at his throat. “He’s a little young, don’t you think?” I hissed in his ear, and the boy pressed against the wall opened his mouth to shriek.

I glared. “I don’t want you. Get, now!”

He didn’t need to be told twice. Slipping around his companion, the boy ran off.

The courtier tried to elbow me. I pressed my poniard on his neck hard enough to give him pause. “Gutter rat thief,” he slurred. “Kill me if you like, but I don’t have anything to give you. That boy-cunny took all my coin.”

“I don’t want your money,” I said. “Just tell me the password. Or would you prefer I turned you in to the night watch for consorting with an underage boy?”

He chortled, swaying. He could barely stand upright. If I hadn’t had my arm about him from behind, he’d have impaled himself on my blade. “That’s a fine one. They’re all underage, you fool. That’s the Nest’s specialty.”

“Password,” I repeated. I pressed harder, enough to make him gasp.

“Fledgling,” he said, and as I lessened my pressure on the blade, he abruptly whirled about, less drunkenly than I’d supposed. I had no choice but to slam him on the side of his head with my poniard hilt.

He dropped like stone.

Grabbing him by his sleeves, I dragged him into the doorway and yanked his mantle from him. It was expensive, a dark green damask lined in fleece, the outer edges trimmed in lynx. I threw it over my own cloak. Hopefully the bastard wouldn’t freeze to death.

Tugging up the mantle’s furred cowl, which almost covered my entire face, I shoved my knife in my boot and strode to the brothel door.

* * *

The clouds overhead had scattered, and the glacial moon now shed a colorless glow over the building. I rapped on the door and waited, counting the seconds under my breath.

A slot in the door slid open. “Fee,” said a gruff voice.

“Fledgling,” I replied.

The sound of bolts grinding preceded the door’s opening. The smell of wood smoke and a blast of warmth greeted me; as I heard the clanking of tankards and laughter, I realized I faced a closed passageway lit by cressets on the walls. There was another door at the end of the short corridor, from which the sounds of entertainment reached me.

The front door slammed shut behind me. A hand yanked back my cowl. The voice barked, “Weapons, if ye please. And yer cloak, too.”

He hadn’t recognized the mantle had a previous owner. Nevertheless, he posed a problem-a titan with the crunched features of a pit mastiff and hands the size of hams. He also had a wheel-lock pistol shoved under his wide studded belt; despite my misgivings, I was impressed. One didn’t see a weapon of that caliber every day.

The man glared at me. Slowly I unhooked my sword harness and wrapped it in both of my cloaks. “Be careful with it,” I said. I had no intention of relinquishing my hidden poniard. He eyed me up and down, my fine Toledo-steel sword gripped in his fist.

“Fee,” he said again.

I frowned, started reaching into my pouch for coin.

“Fee!” he roared.

God’s teeth, were there two passwords? I said coyly, “I’m new, you see, and a friend recommended that I-”

He grasped me by the front of my doublet, thrusting his face at me. If he decided to start using his fists, I wouldn’t stand a chance unless I could get my blade out.

“Who recommended ye?” he asked, and I replied softly, “His lordship the Earl of Devon. He suggested we meet here. He says it’s the finest establishment of its kind.”

“Earl, ye say?” He tightened his fist about my doublet, scrutinizing me. Just as I began to think I was going to have do something very unsavory to get myself out of this predicament, he grunted and let me go, signaling to the door at the end of the passage.

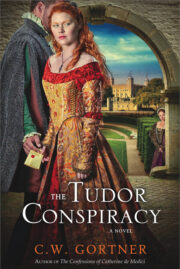

"The Tudor Conspiracy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Tudor Conspiracy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Tudor Conspiracy" друзьям в соцсетях.