Miranda showered and dressed and headed uptown. Though she was acknowledged even by herself to be extraordinarily self-absorbed, no one had ever accused Miranda Weissmann of being selfish.

The apartment was on the tenth floor, just high enough for a spacious view of the park, just low enough for a human one. Central Park was their front yard, Joseph liked to say. Their grounds. He and Betty had tried living in the suburbs when the children were little, in Westport, Connecticut. Dull and lonely there, they agreed, and after only one year, when so many other young couples were leaving the city, they found the big apartment on Central Park West and bought it for a song. That was the word Joseph had used, a "song," and Betty still recalled that day when they signed the papers and went to look at their new home. That sickly ambiance of someone else's old age had surrounded them — the filthy fingerprints around the light switches, the greasy Venetian blinds, the grime of the windows, and an amber spiral of ancient flypaper studded with ancient flies. But all Betty could think of was that they bought it for a song, and she had looked so happy and so beautiful in the weak silver city light that Joseph had not had the heart to explain the expression, to tell her they had paid the song, not received it.

Now they both stalked the premises like irritable old housecats, watching each other, waiting.

"You are leaving me," Betty said late one morning. "Hadn't you better leave, then?"

"Hadn't?"

"I think a certain formality of address is required under the circumstances, don't you? Unless you want to call the calling off off, of course."

There were times when Joe did want to call the calling off off. But that day was not one of them. Betty was being insufferable. She was vamping mercilessly, wearing her bathrobe, speaking in an arch yet melodramatic voice, and, perhaps most alarming of all, drinking shots of single malt in midmorning.

"That's a sipping whiskey. Not a gulping whiskey."

"I'm distraught."

"You're being ridiculous, Betty. You look like something out of The Lost Weekend. This is not healthy, moping around the apartment, drinking."

"My husband of fifty years is leaving me," she said.

Forty-eight, he thought.

As if she'd heard him, she said, "Bastard."

She threw her glass at him.

"All right, Elizabeth Taylor," he said, getting a towel from the bathroom.

"Wrong movie," she screamed.

"It's not a movie, Betty," Joseph said. "That's the point."

"Bastard," she said again. She sat down on the couch.

The buzzer rang, and Betty stayed where she was, staring straight ahead at the fireplace. She had discovered the mantel with its towering mirror and decorative gesso detail at a salvage yard decades ago. How could Joseph expect her to leave her Greek Revival mantel? Her hearth, as it were? She saw her reflection, sullen, in the mirror. The matching busts of impassive Greek Revival women adorned with gold leaf gazed back at her from either side of the mantel. She heard Joseph's footsteps. What a heavy tread he had. How she would miss it when he was gone, when she was alone with the mantel's two white wooden busts. Through the intercom, she heard the doorman announcing Miranda. As a child, Miranda had talked to the fireplace ladies, sometimes staging elaborate tea parties with the disembodied heads as her guests.

"Do you want her to see you like this?" Joe said when he returned to the living room.

For a moment Betty thought he was addressing one of the busts. Then she understood.

"Do you want her to see you at all?" she said. She heard and hated the sound of her voice. Oh, Joseph, she wanted to say. Let's stop all this nonsense now.

They could hear Miranda's key in the lock. Joe thought, I have to get that key back. Annie's, too. He glanced at his wife. She was wearing her old white bathrobe, and curled in on herself on the couch, she looked like someone's crumpled, abandoned Kleenex. Joe winced at his own word, the word "abandoned." No one was abandoning anyone. He would be generous. He was generous. She was being irrational. It wasn't like her. She didn't even look like herself, her face puffy from crying. If she would just be reasonable, everything would be fine: she would be so much happier once she moved into her own place.

"This situation is becoming sordid," he said.

"Squalid even."

Miranda came into the living room, walked to the couch, and gave her mother a kiss.

"Whew," she said, sniffing. "Someone got started early."

"I'm suffering."

Miranda sat down and put her arms around her mother.

"My poor darling," Betty said. "So are you, aren't you? There, there, Miranda darling. There, there."

Joe looked at the two of them patting each other's back and murmuring, "There, there." He felt awkward, an ogre standing with an enormous white bath towel. But what had he really done? Was it so wrong to fall in love?

"This is a very unhealthy situation," he said.

The two women ignored him.

He threw the towel down at the spill and stared at it. "Your mother never drinks," he said. "You have to talk to her, Miranda. I'm worried about her."

There was withering silence. The warm perfume of Scotch whiskey hung in the room.

"I'm not an ogre," he said.

The next day, Joseph packed his bags and left for Hong Kong on a business trip.

"You must be relieved," Annie said to her mother on the phone.

But Betty was not relieved. She was even more miserable than before.

And, too, there was the problem of money. An immediate, acute problem. Unaccustomed, unaccountable. Undeniable. On the advice of Joseph's lawyers, Joseph's lawyers now informed her, Joseph was cutting off all credit cards. The joint bank account, which Betty used for household expenses, would not be replenished until a settlement had been reached.

"I thought Mr. Weissmann didn't want to use lawyers," Betty said to the lawyers. "We have a mediator." The lawyers replied only that they supposed, judging by the evidence of their employment, that Mr. Weissmann had changed his mind.

"I'm awfully sorry," Joseph said when he called. "It was on the advice of my lawyers that I got lawyers."

"Do they advise me to get lawyers, too?"

"We can work this out equitably. It just takes a little time. I'm prepared to be generous."

"Joseph, you're squeezing me out of my own home."

"Well, maybe that would be best. While we settle things."

Just hearing his voice made Betty feel a little better. It was a voice she had heard every day. After the conversation, she felt more herself.

"That's crazy," Annie said when her mother explained this to her. "He's behaving horribly. And you can't move out. That's Divorce 101."

"The co-op is in his name. Legally, it's his. So he just has to straighten things out — legally. Then we'll work it out between us. Until then, he's not really free to let me have the apartment. Legally."

"Mother, you know that makes no sense, don't you? I mean, you do know that?"

"And of course I don't have the money to keep it up just now. Do you know what it costs to maintain a place like this? I'm sure it's a fortune. But I don't really know. Joseph always took care of that part of it. He's always taken such good care of me..." she said with a wistful sigh that was soft with gratitude and comfortable memories.

Annie thought of the little bag with money in it her great-grandmother had always kept hanging around her neck, for emergencies. "Don't you have anything in your own name?" she asked.

"A little knipple like my grandmother? Why should I?"

"Well, in case something like this happened."

"Something like this was supposed to happen thirty years ago, when you girls went off to college, when women were unprepared for something like this."

"But you're unprepared now."

"But it wasn't supposed to happen now," Betty patiently explained yet again.

It was soon after Joseph left that Betty heard from her cousin Lou. Cousin Lou was an elegantly dressed man with a pink face for whom the description open-handed might have been invented. He had, to begin with, disproportionately large hands that burst from his sleeves and were constantly slapping the backs and patting the cheeks and enfolding the helpless smaller hands of the many people he liked to have around him. Lou had come to the United States as an evacuee in 1939, an eight-year-old boy from Austria bringing nothing with him but his eiderdown and a copy of Karl May's first Winnetou novel. Betty's uncle and aunt had taken him in for the duration of the war, but he stayed on after the war ended, for he had lost everyone in the camps. The loss of his family was something he never mentioned. In fact, the only topic from that time that he did talk about was someone named Mrs. James Houghteling.

Mrs. H., as he called her, had been the wife of the Commissioner of Immigration when the eight-year-old refugee had arrived at Ellis Island.

"Now, that same year there was a bill before Congress," he said, the first time he discussed Mrs. H. with the little Weissmann girls. "Do you know what Congress is?"

They nodded yes, though they had only the vaguest idea of men seated in a horseshoe arrangement from a poster in school.

"Then what, Cousin Lou?" Annie said, adding, "Don't worry," for in spite of the parties he always gave, Cousin Lou always did look a little worried.

"That same year," Cousin Lou continued, "someone thought it would be a good idea to allow twenty thousand refugee children to come here, to the United States. Children just like me. Did you know I came here on a boat when I was little?"

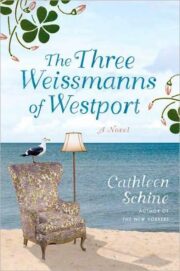

"The Three Weissmanns of Westport" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport" друзьям в соцсетях.