"There you are!" Mr. Shpuntov yelled out, spotting Rosalyn. "Highway robbery. I should have been a plumber, I tell you."

"You were a plumber," Rosalyn said drily. "For fifty years."

Miranda watched Cousin Lou lead Mr. Shpuntov into the dining room. She sat as far from everyone as she could. She ate her goose and her duck and her apple pie. She drank eggnog. She offered Annie the occasional sheepish smile, which Annie returned in kind. She participated in the lighting of the Hanukkah candles. Poor Hanukkah, she thought as she did every year, as if it were a bird with a bent wing she'd found on the sidewalk. It was the third night of the holiday. They had completely forgotten the first two.

15

Frederick's house, gray-shingled, late-Victorian, had been in his family for almost a hundred years. He and his sister, Felicity, had both grown up in the warren of oddly shaped bedrooms and parlors and pivoting stairways. When their parents died suddenly (Arthur Barrow in 1980, Mary the year after), the house was all they left behind. It seemed fitting — two sickly, cranky, frail old people, stranded in the wrong era, leaving behind a house as sickly, cranky, frail, and outdated as they had been, a wood-framed earthly shadow, a leaky memorial. On the day of their mother's funeral, Frederick and Felicity had gone back to the house to accept the condolences of the surprising number of people who attended the funeral. Felicity had prepared sandwiches the night before — small, ceremonial, and now quite dried out. She took the tray out, set it down on the mahogany dining table that had always reminded her of an outsized coffin, then returned to the kitchen. She found her mother's big "festivity" percolator, the one dragged out for Thanksgiving and Christmas and Easter dinner, turned on the faucet, and tipped the percolator clumsily into the sink.

The ancient pipes hemmed and hawed, then sputtered to life. She heard a toilet flush, loud, surprised, exasperated. A family of squirrels had gotten into the attic and worked their way down the walls. With their tiny, verminous claws, they scratched out muffled, secret sounds. Felicity had never liked the house. She disliked the fog, the mournful foghorns, the sound of the ocean, the smell of the ocean — its filthy odor of rotting seaweed and rotting shellfish. She hated the smug insularity of the summer people, and she hated the mirrored smug insularity of the year-round people. It had not been until she made her college escape from Cape Cod to Manhattan that Felicity experienced what felt like fresh air. In New York, she felt as though she could truly breathe for the first time.

She filled the percolator and turned the water off. The pipes gave a strangled sigh. The house was constantly sighing. Structural self-pity.

She had tried to talk Frederick into selling the house even before their mother died. But he was stubborn in his flimsy, easygoing way. "I love this house," he said in response, as if that were a response.

Felicity lugged the percolator out to the dining room and plugged it in. A spark flew from the electrical outlet.

The house's revenge, she thought. Trying to kill me before I can kill it.

But later, she realized that this had been exactly the spark she needed. The spark of an idea. For there she had stood, looking at the frayed cord of the percolator in her hand, at the yellowed plate that surrounded the outlet, at the wood floor that creaked even when no one stepped across it, as if it were a ship struggling through the sea, and the idea, so simple, so obvious, hit her.

She took Frederick by the arm and guided him back into the kitchen.

"You love this house," she said.

Frederick produced one of his looks, the clear dark-eyed expression of a rogue trapped helplessly in his own sincerity, the look that drew so many women to him.

"I'm agreeing," she said. "Christ. I said, You love this house, okay?"

"Okay."

"And I don't want this house."

He sighed and said, "Felicity, it's the day of the funeral. Can we..."

"Buy me out," she said. "It's so simple. Buy me out."

Frederick gave her a fair price, or so she thought at the time. She'd immediately invested the money in the stock market and had done fairly well with it. Still, as time passed and she thought it over, the whole thing didn't seem quite fair. It was almost, well, not exactly shady, but... Over the years, the house had increased in value far more than her stocks had, and that value had then fallen far less than her stocks'. If Frederick sold it now, he'd make a fortune. And wasn't half that fortune really, by rights (maybe not by law, but by rights), hers?

"Well," she was often heard to say to Frederick, "you certainly got a bargain."

"Well," she said to Joseph as they settled into the guest bedroom that had once been her parents' bedroom, "he certainly got a bargain."

The whole family had gathered in the house for Christmas. Gwen, her husband, Ron, and the twins had adjoining rooms on the second floor. Evan was across the hall from them in the smaller bedroom next to Felicity and Joseph. Frederick's room was on the ground floor. He had long ago converted the east parlors, front and back, to his own use — the front parlor with the bow window was where he worked, the back parlor his bedroom. It was there that he stood at the window this Christmas morning watching the insipid winter dawn.

Felicity, lying in bed with a frown on her face, was also looking out the window.

"Joe," she said.

Joseph gave a round, trumpeting snore, followed by a series of liquid burbles.

"Joe," Felicity said again. She turned and pushed his shoulder gently, then more forcefully.

"Sorry," he murmured. The snores retreated for a moment, then came back in force.

Felicity got out of bed, as she had gotten into it, hating the house. The tiny chambers, the sea pounding in her ears — it was like being buried, impotent and rotting, forced to listen to that mocking, immortal sound. And now the snoring. Buried alive with the sea and a snorer. She put on a robe and slippers. Impossible to heat the house. And still it was worth a fortune! She creaked down the stairs.

Frederick heard her. Her tread was instantly identifiable — a quick, sharp step. He met her at the bottom of the stairs.

"Coffee?" he said.

"You're up awfully early." She raised an eyebrow at his rumpled corduroy pants and moth-eaten sweater. He really was absurdly affected.

"I'm not sure I ever went to bed."

"Bad conscience?"

To Felicity's surprise, her brother seemed to start.

"What?" he said sternly. "What do you mean?"

Felicity laughed. "I'm not sure, Frederick. What did I mean? I obviously meant something or you wouldn't look like a dog who's been in the garbage. Have you been in the garbage?"

Frederick considered confessing. Yes, he would say, I have been in the garbage. I have strewn garbage everywhere, and now I must live with it, great stinking mounds of my own garbage, chronic irreversible garbage that I richly deserve and would settle into like Job without complaint, except that it involves an innocent being, a poor wee soul about to be born into a loveless faux family, God forgive me.

"Coffee, yes or no?" he said.

They sat in the kitchen, steam from their mugs rising in the faint wash of white daylight.

"Joe seems like a nice guy," Frederick said. The bland remark expected of him. But Joe did seem like a nice guy. Annie had never told him any particulars about the ongoing divorce, nor did she have to — he had only to look at Betty the two times he'd met her to understand. He had seen a hundred such women, a thousand. They flocked to his readings, to the workshops and classes he sometimes taught. They were an identifiable class of citizens, America's lost souls, like the lost boys of Africa, but they were not boys, they were women, older women, still beautiful in their older way, still vibrant in their older way, with their beauty and vibrancy suddenly accosted by the one thing beauty and vibrancy cannot withstand — irrelevance. Yes, Joseph seemed like a nice guy. And he had done what even nice guys do. Frederick would have liked to feel outrage toward Joseph Weissmann. But he did not dare. His sympathies, he realized sadly, must lie with Joseph now, for they were compatriots, fellows in the fellowship of heels.

"He's a new man," Felicity said. "Thank God."

"You didn't like the old one?"

"Don't be stupid, Frederick."

"Well, you showed great foresight, seeing the new man in the old one."

Felicity gave him a short, searing smile. "We fell in love. He needed me."

"And there, providentially, you were."

Felicity blew her nose. "This house is freezing."

"I like his daughter. Annie. That was a nice gesture, Felicity, getting us together for that reading."

"Oh, that. I thought it might soften the blow. At least you're good for something." She patted his arm affectionately. He was quite a bit older than she was, but he was so unworldly. This frayed wool sweater business, for instance. She picked at a loose thread.

"And what's the other daughter's name?" he said.

"Step daughter. And even so, the man is absolutely devoted to them. As if they were, well, you know, his real daughters. Indulged them, spoiled them. But you just have to be firm as they get older. Strong. When it matters. I think he sees that now, poor, sweet, generous man. Of course, it's all very painful for me, in particular. The stepmother and all."

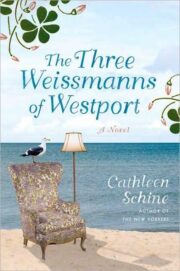

"The Three Weissmanns of Westport" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport" друзьям в соцсетях.