10

The first time Kit and Miranda made love, it was late in the afternoon, two days after they met. Henry was asleep in his crib. The light was golden, saturated, and the white curtains on the windows fluttered noisily in the breeze that swept in from the water. Miranda felt the same arms around her, the Adonis arms, the hero arms that had lifted her from the tossing sea. She laughed out loud, thinking what a fool she was to cast her soggy rescue in such epic terms. When she laughed, Kit told her she was beautiful, that he had found her floating in the ocean and that he would keep her, finders keepers, it was only fair. She allowed herself to disappear, to dissolve into his arms. It was a conscious, almost frenzied release. This was another kind of freedom, this letting go. All responsibility, all aspiration, all disappointment, all of life before that moment was left far, far behind. He undressed her, and she felt her jeans and her sweater, her bra, each bit of clothing slip over her skin. He undressed himself, too, slowly, sure she was watching, she noticed, stringing it out.

They spent almost every afternoon like that, she reeling from the heady emotional simmer: her own fierce, demanding extinction, beneath which rested a calm, solid sense that she was as safe as houses.

When Henry woke up, she would leave Kit asleep in the boathouse and take Henry for a walk on the beach. Tide pools glazed the smooth dark sand, and silver flakes of mica reflected the setting sun. When it rained, they squatted in their slickers and watched the raindrops disrupt the surfaces of the shallow beach puddles. They held hands and spoke in undertones. Miranda had never been religious, but she thought that she could worship Henry with fervor and joy. She thought, I already do.

Cousin Lou was not religious, either: he claimed that he would not like to insult the memory of his benefactress, Mrs. H., by worshipping any god but her. This sacrilegious declaration made both Rosalyn and Betty squirm, but Annie and Miranda laughed every time he said it. In spite of his irreligiosity, however, their cousin could not give up an occasion for a large gathering, and he planned to have thirty for dinner on Rosh Hashanah. The three Weissmanns were invited, as were Kit Maybank and Henry. Among the other guests were a woman Cousin Lou had recently become acquainted with at the Westport YMCA pool during free swim who turned out to be a distant cousin of Rosalyn's; Lou's accountant, Marty, with Marty's large family of several generations; a fellow Lou knew from the golf course who had invented a folding six-foot ladder that was only three-quarters of an inch deep; a plastic surgeon who was always very popular at dinner parties for his willingness to put on his reading glasses and take a closer look; the psychiatrist and his wife; the lawyers; the judge; the metal sculptor; a retired factor from Seventh Avenue; and a former cultural minister of Estonia Lou and Rosalyn had met thirteen years earlier at a spa in Ischia.

When Rosh Hashanah came, a bright, clear, unseasonably warm day, none of the Weissmanns went to synagogue. It had not been their custom for many years, and Betty particularly did not want to this year because, she explained, as one so recently widowed, she could not stand the spiritual strain. So the three women sat on the sunporch and enjoyed the warmth and read the newspaper until, around two o'clock, Kit's white MINI pulled into the driveway.

"They're awfully early," Betty said, eyeing the child in the car seat and wondering if her quiet day was about to be invaded.

Miranda gave her mother a look and went to the car. She could barely contain her excitement. She had just gotten a pair of Crocs that were identical to Henry's own tiny pair of rubber clogs. They were not the kind of footwear she would have ever considered before, not even to wear on the beach, but when she saw them in the store, she imagined Henry's amazement, his pleasure. They were still in the box. She couldn't wait to show him.

She opened the car door and reached in to unstrap Henry.

"No," Kit said, putting a hand out as if to protect the child. "I mean, we're not staying. I mean, we're going."

"But dinner isn't until seven. You can hang out here. Or if you have stuff to do, just leave Henry with me. We have important things to discuss, don't we, Henry?"

"Going on a airplane," Henry said. He clapped his hands.

"An airplane?" Miranda said, clapping in response. "When?"

"Today!"

"Wow! Is the airplane going to take you to Cousin Lou's for dinner?"

He shook his head with vigor. His lower lip pushed out. His eyes screwed shut. And he began, like a thundercloud that blows in with a sudden downpour, to wail.

"Baby," Miranda said, squatting beside the car, reaching in through the open door to stroke his hair. "What's wrong? What's the matter?"

Kit had twisted up his own handsome face uncomfortably. He looked around him, as if searching for reinforcements, then bit his lip, then said, "Look, I'm sorry, Miranda. But we do have to get going... Henry, hush, it will be okay..." He dug in his jacket pocket and pulled out an old, half-eaten Fruit Roll-Up. "Here, Henry. Now stop crying, okay, buddy?"

Henry sucked sadly on the scrap of red fruit leather.

Miranda continued to stroke his head. "My poor little boy," she said softly. "What was all that about?"

Henry kissed her wrist as it passed near his lips. The pressure, so gentle, like a butterfly's wing, seemed to travel through her entire body. She took his free hand and held it against her cheek. This, she thought, is all there is. This little hand. In mine.

Miranda then had a sharp, clear, overpowering vision of holding Henry on her hip while she... well, not while she cooked. No, but while she entered a restaurant. With Kit beside her. She saw them feeding the child bits of California roll, without wasabi, the way Henry liked it. She could feel the bedtime sheets, too, pulling them up as she tucked Henry in at night, could feel his soft, warm breath on her hand as she stroked his cheek. The sweaty, wet sweetness of his body, soggy diaper and all, when he woke up — she clutched that against her; the echoing crunch of Henry eating cereal — she could hear it. Every night, every morning. Then, in a year or so, he would go off to preschool and make wobbly little friends his own age, and she would walk him there, holding his hand, slowing her pace for him, lifting him up when he got tired. Truck, he would call out, pointing at the garbage men rumbling by. He would want to grow up to be a garbage man, and she would look at him proudly and think, You are perfect, Henry. You are perfect, and I belong to you.

When Kit spoke, now standing beside her, she turned a beatific face to him.

"Hmm?" she said. "Sorry..."

"I said we really do have to catch a plane..."

Miranda tilted her head, like a dog, a trusting and innocent dog who has been given a confusing command.

"Plane?" she said, looking up at Kit.

"Listen, I just wanted to say goodbye. It's so sudden and crazy. And I wanted to apologize about tonight..."

"Wait," Miranda said. "What?"

She'd thought for a moment that Kit said he had to catch a plane. Henry's fingers were now splayed out in the air in front of him. She watched them, marveled at them. They were like some glorious, exotic insect. A new species, one she had discovered.

"I got a part," Kit said.

Miranda thought she heard "I've got to part," and wondered why Kit said "I" and not "We," but then realized what he meant.

"Part?" she asked.

"Look, I just found out." Kit was kicking the dirt of the driveway nervously. "It's a real break. I mean, it's nothing, it's tiny, but it's work."

Work, Miranda thought. Work is good. Say something nice. But she felt panicked. Work was what she had loved once. Now she loved Henry. And maybe, just maybe, Kit as well.

"Work!" she said.

Betty observed the threesome from the porch. She thought how much they looked like a family. Perhaps, somehow, against all odds, this improbable arrangement would work for Miranda. If only Miranda could find some kind of domestic peace at last. Betty waved hello to Kit and, followed by Annie, descended the cracked cement steps onto the patchy stubble of lawn.

"Hello, Kit!" they called. "Hello, Henry! What brings you here so early?"

"A part!" Miranda said, trying to smile. "Kit got a part."

"Oh well," Kit murmured. "Small part... Independent film..."

"Kit and Henry are going away," Miranda said in a bizarre sing-song, as if she were addressing Henry, or were insane. "On an airplane."

Betty was visited by the swift, looping nausea she'd had when Joseph announced his departure. She saw Miranda's expression, she heard the loud crashing echo, felt the chill, the vortex. She had been married to Joseph forever, Miranda and Kit had known each other for a month or so. But however long it had been or however short, did it matter? Did it ever really matter? No, Betty thought. A broken heart is a broken heart.

"How long will you be gone?" she asked, though she thought she knew. He had that look about him, that I'm-not-sure-how-long look, that look of goodbye.

"I have to go to L.A.... I don't really know how long," Kit said. He turned back to Miranda. "Look, I'm so sorry about tonight... I mean, I'm sorry period."

Miranda took Henry's hand again. "L.A." She wanted to explain to Kit that L.A. was too far away, that even a short trip was interminable, that one day would be one day too many. She wanted to explain that she had had a vision of their lives together, she wanted him to understand what she had just discovered, that her heart had found a home at last.

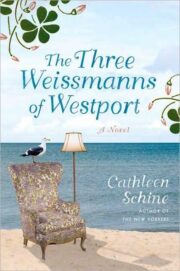

"The Three Weissmanns of Westport" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport" друзьям в соцсетях.