When she got home and heard what had happened and saw her sister, now in a nightgown, huddled on the couch under a cotton blanket, Annie was tempted to deliver a lecture. She had, after all, warned Miranda not to take the kayak out until she had taken lessons, and just last night she had pointed out that the Sound had been unusually rough lately. "Small craft warnings," she had said. "And your craft is minute." But looking at Miranda now, so fragile and vulnerable in her flowered nightgown and striped socks, Annie could not bear to say a word that might hurt her. Instead, she sat beside her on the sofa and put her arms out. Miranda came to her and snuggled in like a little girl.

Annie said, "It all sounds very dramatic." She kissed Miranda on the forehead. Did it feel warm? She laid her cheek against Miranda's forehead. "You have a fever."

"You don't catch cold from being in the cold," said Miranda irritably. "They proved that."

"You still have a fever."

Betty began to bustle in earnest now, throwing another blanket over Miranda and attempting to spoon chicken soup into her mouth. "I read that they did an experiment in Scotland with students. They put their feet in buckets of cold water and exposed them to germs."

"What happened?" Annie asked.

"Well, I really can't remember. But it sounds so unpleasant. I've never liked Scotland. Here," she said, putting a thermometer in Miranda's mouth.

"You just gave me soup." Miranda tried to hand the thermometer back to her mother. "My temperature will be 110 after soup."

"All the more reason," Betty said firmly. And she replaced the thermometer in her daughter's mouth, where it belonged.

When Cousin Lou came by on his customary evening walk, something prescribed by his doctor for his heart which he converted into a promenade from neighbor to neighbor to chat and invite them to his house for various meals, he discovered Betty fussing over a feverish but contented patient while Annie washed the dishes.

"She was rescued by a young fisherman," Betty said.

Annie, listening from the kitchen, just able to hear her mother over the running water, smiled to herself. Betty made the young man sound like a Scandinavian in a cable knit sweater crashing about in the Barents Sea.

"By my friend Roberts? Ah ha! I saw him out with his fishing gear this morning. I knew he had eyes for you, Miranda. And now he is your hero. Although I don't think I would call him young."

"Eyes for me?" Miranda said. "He was practically mute when I sat beside him at dinner, if that's who you mean."

"Mute, but not blind to your charms," Cousin Lou said.

"Well, whatever his disabilities, poor man, it wasn't him, anyway," Betty said. "It was a young man who spoke very nicely and didn't even need glasses, unless he wears contacts, which is possible, you never know. His name was Kit Maybank, isn't that right, Miranda? A pretty name. Maybank. Like a pile of dirt in spring."

Miranda, the thermometer again in her mouth, nodded.

"Maybank." Lou sniffed. "Hoity-toity goity and moity." He wore his Mrs. H. expression, and Miranda steeled herself for a chechtling parable, but he just patted Miranda affectionately on the head and said, "Well, well, never mind. Oh, poor unsuspecting Roberts. Forgotten so soon for young Maybank."

"Oh, for heaven's sake, Cousin Lou," Miranda mumbled, the thermometer wiggling absurdly. "Roberts is old enough to be my father."

"At least someone is," Betty said. "Now that Josie has dropped the ball."

Miranda went to bed feverish and flushed, her hair flat against her head, her eyes swollen with fatigue. The next morning, however, she emerged from the bathroom brisk and freshly showered, looking and feeling like herself — her pre-Oprah self. When Kit Maybank came up the dirt path to the ramshackle cottage, he was not prepared for the radiant woman who met him on the sunporch. He remembered a gasping, pale, wet, older woman from the day before, not this vibrant being with the mocking smile and deep, avid eyes.

After pushing the screen door open, Miranda looked down from her vantage point atop the concrete steps. There was the Adonis, a hank of his dark silky hair falling across his forehead. And there beside him, his little hand clutching the larger hand, was an identical tiny Adonis, a boy of two or three, she guessed. They both smiled at her. Then the child put his hand in his mouth. Miranda watched, fascinated, as his fist twisted until it disappeared completely into the little mouth and the child blinked contentedly.

Kit had returned out of an agreeable feeling of importance and friendly condescension toward the lady he had rescued. But now, facing this surprisingly attractive woman who had darted out the door and given him a long, assured, assessing look, he was, for a moment, as mute as Roberts. Then she looked at Henry, his little boy. He saw the quizzical expression, the swipe of her hand in front of her face, as if wiping away an unexpected drizzle of rain.

"Henry," he said. "This is my son, Henry."

The child, removing his hand from his mouth, said, "Henry" in a slurred child voice.

"Henry, this is..." He forgot her name, then quickly, but not quite quickly enough, remembered. ". . . Miranda."

She gave a short, sardonic laugh, from deep in her chest, peering down at them from the cracked concrete pedestal. "How do you do, Henry?" She came down from the steps.

"Henry," the child said again, throwing a quick glance at his father, as if confirming the fact.

"Mini-me," Miranda said. Henry was wearing a petite version of his father's outfit: miniature khaki pants, Top-Siders that might have been made for a doll, a madras belt the size of a dog collar, and a postage-stamp-size pink oxford shirt.

Kit handed Miranda the enormous bouquet of wildflowers he had picked from the meadow behind his aunt's house.

"You're awfully dry today," he said.

"I try not to drown more than once a week."

Miranda invited them in. She arranged the flowers in a vase and placed it on the sunporch. "I love wildflowers," she said. "But I should be the one bringing flowers. And burnt offerings." She put her hands on her hips and tapped her foot, staring at the little boy, who had one small arm wrapped around his father's calf. "Cookies," she said.

She left them, and Kit watched her go, trying to ignore her tight, quick, sexy walk. When she returned, she was carrying a plate of cookies in one hand and the pants and sweater he'd lent her the day before in the other.

"This is the only tribute I have to pay at the moment," she said.

They sat on the wicker furniture in the sunporch and watched Henry eat cookies.

"He's two," Kit said. "His mother..."

Miranda was suddenly alert. His mother was... institutionalized? Dead? She felt a confession coming, a story, a tale of misery transcended...

"His mother is in Africa doing research for two months. It wouldn't have been safe to take him. She's an epidemiologist."

The child sat down heavily on the floor, then popped up and spun around, his arms out, his fingers splayed.

"We're divorced," Kit added.

She saw him blush. Or was she the one who blushed?

"So I've got him all to myself for a bit, don't I, little guy?" Kit continued quickly. "With a little help from Aunt Charlotte and her indomitable housekeeper, Hilda. Who might as well be named Mrs. Danvers. Henry, what does Hilda say?"

"'No, no, no,'" said Henry, shaking his finger.

He then ran from one end of the room to the other and came to a sudden stop in front of where Miranda sat.

He climbed into her lap and held a soggy, ragged remnant of a cookie up to her mouth.

Miranda felt the cookie on her lips, like damp, sweet sand. An oatmeal cookie. When they were children, they called oatmeal cookies "Josie cookies." She could not remember why. She looked at the big pale gray eyes of the child. His mouth was crusted with cookie detritus. His nails, dug into the cookie, seemed no bigger than five little kernels of corn. She nibbled at the cookie and saw his face light up and held him, suddenly, close to her breast.

"Thank you," she said softly. "Thank you, little Henry."

When Kit was strapping Henry into his car seat, he was aware of Miranda behind him. He turned and saw her, those remarkable eyes aimed right at him.

"I owe you," she said.

He shook his head, all the time watching her watch him. She took his hand. He heard himself suck in his breath, stirred, and wondered if she heard it, too. She was far too old for him, though he suddenly could not tell how old that actually was. Nor, he realized, did he care. He had fished her out of the sea. He could still feel the weight of her wet body. He quickly turned back to Henry. There was something depraved about even thinking of such things in front of one's son. And yet one did. The sky had cleared overnight, and the late-summer sunlight was deep and slanted and warm. She was wearing some kind of scent. Henry was kicking his feet against the car seat. Bing bang, bing bang.

"You have paid your debt with cookies," he said.

"No, no. Here's what I'll do," she said. "I'll take you out to dinner."

Her voice was low and straightforward. She was clearly used to people doing what she told them to do. He wanted to do what she wanted him to do.

Henry was singing now. Something from a cartoon show. Kit said, "Henry, say goodbye to Miranda."

An obliging child, Henry waved his small hand. He called her Randa, and she smiled and waved back.

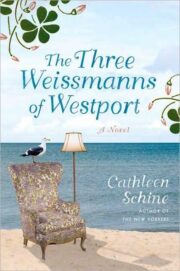

"The Three Weissmanns of Westport" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport" друзьям в соцсетях.