Normally Miranda would have commented on two pedantic outbursts in such a short period of time, but she was more indulgent of the Mitford family, awed by the number of memoirs, biographies, and scandals the sisters had generated.

"She thought it was too expensive," Annie continued, "so they just stopped using napkins."

"But think of the cleaning bills for their clothes," Betty said, clucking. "Although they could have used paper towels, I suppose..."

Betty and Joseph's housekeeper, a Brazilian woman named Jocasta who had retired last year, had always gotten the napkins snowy white and ironed them into crisply folded rectangles. When they first came to the cottage, Betty had suggested sending them to the dry cleaner, or at least the fluff-and-fold laundry downtown called the Washing Well, but Annie had put her foot down.

"We have a washer and a dryer. It's about the only thing that works in this house, so we might as well use it and not waste money."

She was, therefore, responsible for the napkins herself. They had acquired a few yellow stains, she noticed, and she certainly was not going to stand around for hours watching soap operas and ironing them the way Jocasta had. She placed the rumpled stained cloths beside her mother's good china. The napkins looked disgruntled, rebellious, like a crowd of disheveled revolutionaries. Maybe they should use paper towels, after all.

"Wash your hands before dinner, girls," Betty said.

Girls again. Could you re-create your childhood in a new place at an advanced age and without one of the key players? Annie wondered. For better or for worse, that's what they seemed to be doing. Oh, Josie, what were you thinking, leaving us here to play house, three place settings instead of four? "The Odd Trio" Miranda had dubbed them, but it was clear from the outset that they were, all three, the fussy one, each pursing her lips in disapproval of the other two, each missing the man who was not there.

"I can't imagine what all the neighbors think we're doing here, three old broads in this ramshackle house," Annie said as she watched a woman walk a big galloping black dog down the street.

"Oh, they think we're Russians," Betty said.

"Why?"

"Because that's what I told them."

Annie pressed her forehead against the window. Russians?

"Refugees!" Miranda said, delighted. "Cousin Lou must like that."

"Yes. I said we had all lost our poor husbands."

"How?" Annie asked.

"KGB, dear. How else?"

Those first few weeks of the Weissmanns' sojourn in Westport had about them both a reassuring and a festive air. The weather was holiday weather — unusually cool for late August, the blue of the sky clear and deep, a few bright clouds rolling by. There were ferocious showers in the afternoons now and then, as if they were in the tropics. Then the rain would pass, leaving the air fresher than ever, the light golden, clean, and rich. In addition, Betty was a wonderful cook in a traditional way that Annie and Miranda both associated with holidays, and it was Betty who did most of the cooking on the old stove. None of them was sure how this had happened — it had never been discussed or formalized in any way. But somehow, Betty was cooking for her children as she had done so many years before. The only exceptions came when the three women were commandeered for dinner at Cousin Lou's. Betty said it was cruel to deny him their company, particularly when he was being so kind about the cottage. She did not say that she was seventy-five years old and sometimes cooking dinner was tiring. Nor did anyone ask.

At one of these Cousin Lou dinners, Miranda was seated next to a tall, serious man, as stately as a house in his dark, smooth suit. He might have been nice-looking if he hadn't seemed quite so formal and hadn't been wearing a bow tie. But he was formal, he was wearing a bow tie, and after releasing the information that he was a semiretired lawyer, he said very little else. Miranda, who liked to listen and was so good at it, tended to interpret reticence as a personal insult. However, she was always willing to give people a second chance.

"What do you do now that you're retired?" she forced herself to ask. "Or, I should say, semiretired?"

"Fish."

"Really? Fish has become so stressful."

He gave her a perturbed look. Has they? he wanted to ask.

"Ordering it, I mean."

"Ah. It."

"Aren't you worried about global warming and overfishing and mercury?"

"Oh, I never catch any."

After this, the conversation refused to take even one more ungainly step, and Miranda, defeated, turned to the person on her other side, her cousin Rosalyn.

"You must be very bored in our quiet little town," Rosalyn said. She had seen Miranda trudging back from heaven could only guess where with an armful of weeds, a great, tendriled burst of them, surely crawling with bees and ticks, which Miranda then brought up to the house and offered as a bouquet. Rosalyn, who had a horror of Lyme disease, made sure they were thrown away as soon as Miranda departed. Still, it was sweet of her, in her thoughtless, careless way. Poor Miranda. She had to fill up her time somehow after her unfortunate professional downfall. What a scandal that had turned out to be. It was all over The New York Times, though it was really just an insular publishing scandal, after all. Nothing for Miranda to get on her high horse about, even with that piece about it in Vanity Fair.

Rosalyn had thanked dear Miranda for the buggy weedy bouquets she brought, offering les bise with just the right show of warmth — neither too much nor too little. Just because someone was down and out did not mean they should be treated coldly. On the other hand, she could not help thinking that it was inconsiderate of Lou to place his cousin next to her when there was such an interesting woman at the other end of the table, a reporter, younger than Miranda, still in her prime, really, someone at the top of her game professionally, rather than on the way down. Well, she supposed someone had to talk to Miranda. It might as well be the poor hostess. Unpleasant things usually did fall to the hostess. "Very bored after all the excitement of..." Rosalyn paused. She had been about to say "of your past life." But Miranda was not dead. She had not even officially retired. She was just washed up. How did one say that politely? She decided on ". . . the excitement of big city life."

Miranda was gazing in fascination at Rosalyn's hair. Newly tinted a rusty red, it was a work of art, an edifice so delicately, elaborately wrought it took her breath away. How could she possibly be bored with such a hairdo to contemplate?

"You seem to have so much spare time," Rosalyn was saying. "I envy you!" she added, feeling in truth only a soft, snug pity.

"Yes, there are so many new things to see here." Miranda tried to look Rosalyn in the eyes rather than staring at the taut curved wall of hair rising above her ear. "Richard Serra," she added softly. Rosalyn's marvelous hair looked like a Richard Serra sculpture. Even the color.

"No, I don't think he lives here in town. Though, of course, Westport has always been such an artistic place."

When Betty last lived in Westport, there had been a butcher downtown with sawdust on his floor and a cardboard cutout of a pig in his window. There had been a five-and-dime, too. Woolworth's? No, Greenberg's, she remembered now. That was more than forty years ago, yet she felt that if she turned her head quickly enough she might still catch a glimpse of the store's wooden bins filled with buttons and rickrack, of the Buster Brown shoe store next door to it. When she looked at the bank now, she saw the Town Hall it had been. The Starbucks had been the town library, the Y the firehouse. The memories appeared like visions. They laid themselves out like a path to the past. But really they were just a path that led, inevitably, to this moment: Betty Weissmann driving through a town she had long ago deserted, without the man who had deserted her. That's what Betty thought as she parked behind Main Street, facing the river. Her memories all led her here: a parking lot, lucky to get a space.

She got out of the car and locked it. In the days when she had been here with Joseph, she had never had to lock the car. She blamed him for this. It had become her habit to blame him for so many things. That's what you get, Joseph — unfair and extravagant blame. A small price to pay for jettisoning your wife, for chucking her out to spin helplessly in the dark, infinite sky of elderly divorce.

A spurned woman has to look her very best when the spurned woman goes into the city to meet with the man by whom she has been spurned. Not to mention the lawyers who helped him. For this reason, Betty decided to buy a silk sweater at Brooks Brothers and a pair of gold knotted earrings at Tiffany's. Her credit cards were useless, thank you, Joseph, but Annie had added Betty onto her Visa for emergencies, and if this wasn't an emergency, what was? Then Betty bought a suit — ideal for a meeting with lawyers, elegant and dignified — at a large store full of overpriced well-made fashionable clothing. She remembered it as, in decades past, a nondescript men's shop. The store had prospered, and the suit she bought there, extremely expensive, was for those who had prospered along with it. She was not supposed to buy clothes like this anymore. But spurned women, like beggars, could not be choosers. No one could object to this girding of her loins, she thought, anticipating Annie's voice doing exactly that.

Betty took the train in. When the conductor punched holes in her ticket, she found the old-fashioned mechanical click comforting. The train was creaky, the window bleary. The drive into the city was just too much for her these days. Left cataract needed to be taken care of; she would have to get to that. Right now, it was important to get her hair done. She'd left herself plenty of time. Annie said she would have to stop going to Frederic Fekkai, but Annie, in spite of what Annie thought, was not always right.

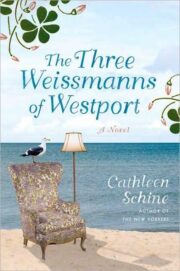

"The Three Weissmanns of Westport" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Weissmanns of Westport" друзьям в соцсетях.