“What remedy do you propose?” asked Mary.

“Ah, Your Highness, if you would be content to be a wife only and promise to give him the real authority as soon as it comes into your hands, I believe that the differences which are now between you and the Prince would be removed.”

The differences? He would no longer keep a mistress? He would be the perfect husband she had tried to deceive herself into thinking he was? This had been between them, then, this knowledge that she could one day be a Queen and he only assume the title of King if it were her wish? Mary was excited. She knew William and his pride. That was the answer then. He had avoided her because her position could be so much higher than his. He could not endure to be merely a consort to a Queen; his pride was too great; just as it was too great for him to ask her what she intended to do. It had been between them all those years. She, too blind to see it; he, too proud to ask.

And so he had turned to Elizabeth Villiers who to him was merely a woman whom he could love—not a Princess who could one day be a Queen and hold his future in her hands.

Mary, sentimental, idealistic, believed that wrongs could be righted in a moment of illumination.

She turned to Burnet, her expression radiant.

“I pray you bring the Prince to me. I will tell him myself.”

When Burnet brought him to her, assuring him that she wished to tell him herself the answer to the question, she went to William and taking his hands kissed them.

“I did not know,” she said, “that the laws of England were so contrary to the laws of God. I did not think that the husband was ever to be obedient to the wife.”

William’s heart leaped in exultation, but his expression remained cold. He wanted a definite statement before he committed himself.

“You shall always bear rule, William,” she told him.

Then he smiled slowly.

She added with a joyous laugh: “There is only one thing I would add. You will obey the command: ‘Husbands, love your wives’ as I shall do that of ‘Wives, be obedient to your husbands in all things’.”

“So,” answered William slowly, “if you should attain the crown, you will be Queen of England and I shall be the King?”

“I would never allow it to be otherwise,” she told him lovingly.

“If you once declare your mind,” Burnet reminded Mary, “you must never think of retreating again.”

“I never would.”

“Then,” said Burnet smiling from one to another like a fairy godmother, “this little matter is settled. When James goes, there will be a King and Queen of England.”

“And the Queen will be a woman whose one desire will be to obey her husband,” added Mary.

Those were happy days.

He shared confidences with her; theirs was a happy trinity—Burnet, Mary, and William; and they talked of England as though in a week or so they would all be there. The King and his Queen, who would always see through his eyes and obey him in every way; and Burnet, who would become a Bishop and remain their friend and adviser.

There was only one question that Mary could not bring herself to put to her husband: “Is it finished between you and Elizabeth Villiers?”

It would not have been difficult to find out. She could have had her spies who would soon discover the truth; she could have waited in the early hours of the morning to catch him as she had before. But she would do none of these things; she would only believe that she had attained the perfect marriage for which she had always longed.

William stood in his mistress’s bedchamber looking down at her lying on her bed.

She grew more attractive with the years, he thought; her wits sharpened and her beauty did not fade, for it was more than skin deep. It was in the strangeness of her eyes, in her sensuous movements, in her low laughter, so indulgent for him.

“She will obey me in all things,” he told her. “She has said I shall always bear the rule. It is what I have waited to ask her for years and now, thanks to Burnet, she has told me herself.”

“And she asks no conditions?”

“She mentions none.”

“I thought there might have been one.”

Elizabeth looked at him passionately for a moment; then she rose and gracefully put herself into his arms.

“To abandon me?” she whispered.

“It is one condition to which I should never agree,” he told her.

THE CONFLICT OF LOYALTIES

There was consternation at The Hague. Mary Beatrice was pregnant. If she bore a son then he would be heir to the throne and if he lived that would be the end of Mary’s hopes of being Queen of England.

William was in a black mood.

To have come so far and now be frustrated! It was more than he could endure. The three crowns, which Mrs. Tanner had prophesied would be his, had such a short while before seemed almost within his grasp; and now there was this alarming news.

If James had a son, that son would be brought up as a Catholic. How could it be otherwise, when he had a Catholic mother and father? The return of Catholicism to England would be assured.

It should not be allowed to happen.

William secretly believed that the people of England would never allow it to be.

The Princess Anne wrote from England, for she too was horrified by the news, so horrified that she simply refused to believe it.

“The grossesse of the King’s wife is very suspicious,” she wrote. “It is true that she is very big, but she looks better than she has ever done which is not usual in the case of women as far gone as she pretends to be …”

William read the letter with growing excitement. Envoys were arriving from England with secret messages for him and Mary. There was a rumor being spread through England that there was no truth in the Queen’s pregnancy; that she flaunted it, was over-big and behaved in an exaggerated manner as a pregnant woman as though she was eager to call attention to her state every moment of the day. She was certain that it would be a son. Over-certain some said, as though it had been previously arranged.

The people in the streets were murmuring against the King and Queen. They did not want a Catholic heir and they were determined to prove there was no true one on the way.

As the summer wore on the tension increased. The Princess Anne, unknown to her father and stepmother, was at the head of those who were determined to cast doubts on the Queen’s true pregnancy. Anne, staunchly Protestant, had grown to hate her father, although she had never shown him that she had. She was looking ahead to the day when she would have the throne. Sarah Churchill was certain that she would, and then ultimate power would be hers—or Sarah’s. Anne was fond of her pleasant weak husband, but it was Sarah to whom she listened, Sarah on whom she doted.

Mary had no children so after Mary it would be the turn of Queen Anne; and now there was this child—or this supposed child—to oust them from their place.

Angrily Anne wrote to Mary. “I have every reason to believe that the Queen’s great belly is a false one. Her being so positive it will be a son, and the principles of that religion being such as they will stick at nothing, be it never so wicked if it will promote their interest, makes it clear some foul play is intended.”

Mary took the letter to William. They pondered on it; he dourly, she anxious because of his disappointment. If she could no longer bring him the throne he craved, she feared she would no longer have the same value in his eyes and she knew that that value had been enhanced when she had promised that he should rule her as well as England.

“William,” she said, “why should my father pretend that the Queen is with child?”

“Because,” replied William sourly, “they care for nothing so long as they can bring England back to popery. They will thrust a spurious child on the people—and that child will be a Catholic.”

“Oh, William … my father would not be so wicked.”

“Mary, it is time you looked at truth. It is unpleasant, but no good can come of looking away for that reason. Your father is an evil man. Accept that truth and you will suffer less.”

She turned away from him and there were tears in her eyes.

“He was so good to me when I was a child. He loved me, William.”

“You are a fool,” said William brusquely and left her.

She wept a little.

It was so sad when there were quarrels in families but she must not forget that it was her father who had murdered Jemmy the man she … the man for whom she had had such regard.

Her father was a Catholic. He was trying to foist a child, not his son, on the people of England for the sole purpose of thrusting them back to Rome.

That was wicked. That was evil.

It was something no one should forget or forgive.

James’s flair for projecting himself into trouble had not left him. While the country was listening to the stories put about by his enemies that his wife was pretending to be pregnant he brought forward his second Declaration of Indulgence which he ordered should be read in church on two Sundays. Seven Bishops petitioned him against the declaration, which James declared was rebellion against the King. These Bishops were sent to the Tower.

There was murmuring throughout the country. In Cornwall, since one of the Bishops was Jonathan Trelawny, the brother of Anne who had been sent out of Holland by the Prince of Orange, they were singing

And shall Trelawny die

Then twenty thousand Cornishmen will know the reason why.

And all over England there was equal resentment against the King. How much easier it was to believe of a King that he was preparing to foist a child on the nation in order to secure Catholic rule, when he imprisoned his Bishops because they disagreed with him on what should be done in the churches.

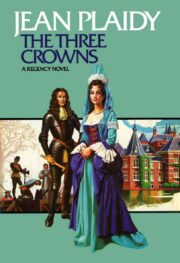

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.