William sent for Mary when he received this letter.

“Your father believes he can dictate our conduct to us, it appears,” he said coldly.

Mary sighed. She hated trouble between her father and her husband, and always sought to put their differences right.

“I can understand his feelings. Dr. Burnet did preach against him.”

“For which one can only admire Dr. Burnet.”

“He is a brave man, certainly, and firm in his beliefs. I understand Dr. Burnet, William, but I also understand my father.”

“You understand his desire to bring Catholicism back to England? You understand the cruel treatment of Monmouth?”

Mary winced; she could never think of that tragedy without a deep and searing pain; and in spite of her sense of justice and her natural tolerance she felt a sudden hatred for a father who had destroyed one whom she had loved.

William went on. “And not only Monmouth which is perhaps understandable. Those others, those men who fought for him because of their convictions—what do you think of the justice they received at your father’s hands?”

“I think Judge Jeffries was to blame and that my father had no real knowledge of what was going on.”

William gave one of his rare laughs. It was not pleasant.

“I doubt whether you understand what it is like to be a slave on a Jamaican plantation. Transported from England to that hell. Yet that was the fate of many of your father’s subjects … for what reason? Simply because they hated popery.”

Mary said: “It was wrong to be so severe. But we must not forget, William, that Monmouth called himself the King.”

“It might have been that others called him that. But if you wish to excuse your father, do so. I have no wish to listen.”

“William, I do not excuse him. I …”

“Then,” said William curtly, “it may be that you begin to understand him?”

He left her and she thought of Jemmy, dancing with her, teaching her to skate, teaching her so much more than she could ever speak of; and she wept afresh for Jemmy.

Jemmy dead, bending to the block; and the cruel executioner lifting that once lovely head and crying: “Here is a traitor!”

“A traitor,” she said vehemently, “to a tyrant!”

And she knew then that she was beginning to feel toward her father as William wished her to. She was beginning to see him through William’s eyes—libertine, ineffectual ruler, the King who, while he did not declare himself openly a papist, was trying to thrust popery on a country, the majority of whose people rejected it—all that and the murderer of Jemmy!

Gilbert Burnet came to her in some haste.

“Your Highness,” he said, “something must be done. The Prince is in danger.”

Mary grew pale and cried: “Tell me more. What do you mean?”

“I have spoken to His Highness and he shrugs it aside. You know that the King of France regards your husband as an enemy.”

“I know all these things. Tell me quickly.”

“I have discovered a plot to kidnap the Prince when he drives unattended along the Scheveling sands. The idea is to get him out of Holland into France.”

“And you have told the Prince this?”

“I have warned him and he says he will know how to take good care of himself.”

“And he will take no guard with him?”

“I fear not. He said that what is to be will be and if it is destined that he shall meet such a fate then so be it.”

“I must go to him at once,” said Mary. “Pray come with me, good Dr. Burnet.”

Together they went to the Prince’s apartment. William raised his eyebrows when he saw them together; but Burnet detected the faint pleasure which showed in his face when he beheld Mary’s agitation.

“William, you must take a guard with you when you go on to the sands.”

“So, you have heard this warning?”

Dr. Burnet put in: “Your Highness, I am convinced there is a a plot and that you are ill-advised to ignore it.”

Mary clasped her hands together. “You must not ignore it, William. It would be disastrous if you were forced into France.”

William looked impatient, but Mary went closer to him and looked imploringly into his face.

“William, I beg of you, to please me …”

William shrugged his shoulders.

“Very well,” he said, “I shall take the guard.”

Mary paced her apartments in agitation. She would not rest until William returned.

She sent for Dr. Burnet and asked him to pray with her.

When they rose from their knees William had still not returned.

“Dr. Burnet, do you think the plot could have succeeded in spite of the precaution he took?”

“No, Your Highness. The Prince will soon be back in the Palace.”

“I shall know no peace until he is.”

Burnet looked at the Princess intently. He was a man who had little restraint and the intimate friendship he had enjoyed with these two had put him into a position he believed where he could speak his mind.

“Your Highness,” he said, “your devotion to the Prince is obvious. Yet I do not think there is always accord between you.”

Mary looked startled and was about to show her displeasure when Burnet said quickly: “If I speak rashly it is because I have your happiness and that of the Prince at heart.”

“I know this,” she said, and moved to the window. Burnet saw that the subject was closed.

But he did not intend to let it rest if he could help it.

Mary said she would pray once more, for the longer the Prince’s absence the greater became her anxiety.

They were on their knees when the sounds below them told them that the Prince was returning to the Palace.

Mary ran to the window. There he was riding at the head of the guards. On horseback it was scarcely visible that he stooped distressingly and that he was so slight.

Mary turned to Burnet. “How can I thank you?” she said.

“By letting me help Your Highness in every way possible,” was the answer.

Burnet was in higher favor than ever, particularly with the Princess, and, when they were alone together, with habitual temerity he broached the subject of her marriage once more.

This time Mary did not feel she could rebuff the man who had saved her husband from being kidnapped, possibly murdered, so she allowed him to speak.

“I believe the Prince has a great regard for you, but there is something which holds him back from expressing his affection.”

Mary said frankly: “The Prince has never expressed great affection. I do not believe it is in his nature to do so.”

To Elizabeth Villiers? Burnet asked himself, wondering whether to mention that lady and then deciding not to.

“I believe,” said Burnet, “that the Prince is always aware that the crown of Britain would come to you and that in the event you would be the Queen and he merely the Queen’s consort.”

Mary opened her eyes wide. “Surely the Prince knows that I would never put him into a humiliating position.”

Burnet was secretly delighted; he believed that he was going to bring about a deeper understanding between the Prince and Princess of Orange which would be a great advantage when, as he hoped, they came to England to depose James.

“Your Highness,” said Burnet to the Prince, “in the event of James dying or … some other contingency … and the Princess being acclaimed Queen, has Your Highness considered your own position?”

Even William was unable to hide the depth of his emotion.

This is the secret, thought Burnet; this is at the very heart of the matter.

“You can rest assured,” said William sharply, “that nothing would induce me to act as valet to my wife.”

“Nothing would induce me to believe that she would expect Your Highness to.”

“When greatness comes one cannot always assess the effect it will have.”

“But the Princess …”

William waved a hand. “The Princess has been a docile wife … almost always, and only rarely has she opposed my wishes.”

“Almost.” “Rarely.” Those were the significant words.

So William was unsure of his wife, and it was a barrier between them. He could not bring himself to ask her what position, if she were Queen of England, she would assign to him; and the ministers of England would accept her as their sovereign; they would obey her, and if she said William was to be her consort merely, that was all he could hope for. The decision lay with Mary; and he did not fully understand Mary.

It was clear to Burnet that this was a question which burned continually in his mind. He was working toward a goal; he had married Mary in order to reach this goal; and now he did not know whether this meek obliging wife would, in one of her sudden moods of firmness, withhold from him that which had come to be the very meaning of his existence.

“Your Highness, I could put the question to the Princess … with your permission. I could discover what is in her mind.”

William’s pale eyes seemed to take on new life. He gripped Burnet’s arm.

“Do that,” he said.

So once more Burnet sought Mary.

“Your Highness,” he said, “I have just left the Prince and there is a matter which perplexes him greatly and which I believe is constantly in his mind. Have I your permission to right this matter between Your Highnesses?”

Mary, looking puzzled, implored him to go on.

“It is simply this, Your Highness: should you succeed your father to the Crown, what position do you intend the Prince to hold?”

“I do not understand you. What comes to me, comes to my husband, does it not?”

“That is not so. You will remember that when Mary Tudor came to the throne her husband Philip of Spain was not King of England. Your Highness, I do assure you that a titular kingship is no acceptable thing to a man—particularly when that is his only as long as his wife shall live.”

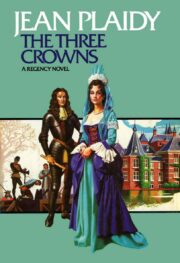

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.