THE VITAL QUESTION

Mary was twenty-four years old and would have been very beautiful indeed had she not grown so fat. The people of Holland delighted in her; for whenever she went among them her manner, while gracious and charming, was undoubtedly friendly. She was a contrast to her taciturn husband; she had a measure of that Stuart charm which Monmouth had possessed to a great degree and Charles overwhelmingly, and which usually meant that, whatever their faults, there would always be some to forgive them.

Mary, it seemed to those about her, had few faults. Perhaps she would have been understood better if she had had. She loved card playing, but that could not be called a fault; and although she was friendly in general, after the departure of Anne Trelawny she did not make a close friend of anyone.

They did not entirely understand her, so they remained aloof; her docility to her husband was interrupted now and then by those outbursts of firmness which showed themselves in the part she had played in the Zuylestein marriage and in sending Elizabeth Villiers to England. She was meant to be gay and vivacious as she had been in the days of childhood; but life with William had subdued that. She had become devoutly religious, devoted to the Church of England—and to her husband. Those about her believed that no one could love a man like William as she professed to do, and that her obvious devotion was like a religion to her. She had chosen it as the right way of life and determined to pursue it. Those who remembered how gay she had been during the visit of the Duke of Monmouth were certain of this. Mary, because of some strange bent in her nature, was determined to subdue her natural impulses and become the sort of person she felt it her duty to be.

She knew that Elizabeth Villiers continued to be William’s mistress. For some time she had visited William at the Palace and now was installed in her old position, yet Mary preferred to ignore it. Neither Elizabeth nor William ever mentioned to her that trip to England; it was as though it had never been.

Her women said that they could not understand a woman in her position accepting what Mary did; and Mary was an enigma.

She was to William also. If he could have been sure of how she would act in the event of ascending the throne of England, his entire attitude toward her would have changed. He could have talked to her more freely of his plans; but this stood between them; and he could not bring himself to talk openly of the position she would expect him to hold. Although to all outward appearances he had subdued her, yet he was afraid of her; and although she was the meek wife, seeming always to bend to his will, yet it was in her power to exclude him from the brilliant future which had been his goal ever since he had contemplated marrying her.

This was the state of affairs when Gilbert Burnet arrived at the Court of The Hague.

Gilbert Burnet was in his forties when he came to Holland. He had been a favored chaplain of Charles II but he had quickly fallen foul of James, for he deplored the threat of papacy. It became clear to Burnet that while his position was precarious under Charles, for his friends Essex and Russell had been involved in the Rye House Plot, it would be untenable under James. After that plot he had left England for France where he was warmly received.

One of the first things he did on returning was to preach a sermon against popery which was received with wild enthusiasm by an anti-Catholic congregation; and when Burnet thundered out: “Save me from the lion’s mouth; thou hast heard me from the horn of the unicorn …” the applause rang out in the church, for the lion and unicorn were the royal arms and this could only mean that Burnet when denouncing popery was denouncing James.

After that there was only one thing for Burnet to do—leave the country. He had been writing busily for the last few years and had produced his History of the Rights of Princes in the Disposing of Ecclesiastical Benefices and Church Lands among other works. He was a man whom James could not afford to keep in England.

Burnet went to Paris where he remained until the repercussions of the Monmouth rebellion had subsided; then on to Italy and Geneva and eventually, receiving an invitation from the Prince and Princess of Orange, he arrived at The Hague.

William received him coolly. He was not sure that he trusted him completely for in his opinion the man was apt to talk too much. Burnet was without fear, there was no doubt of that, but the fearlessness made him indiscreet; and William always mistrusted indiscretion. With Mary, Burnet was on happier terms. She was interested in what he had to tell her of England and his travels, and would ask him to sit with her and while he sat she knotted fringe, for she had had to give up doing the fine needlework on which she had enjoyed working, since her eyes had given her so much trouble.

This was a pleasant domestic scene and sometimes William would join them and listen to the conversation.

Burnet believed that James could bring no good to England and for this reason William became gradually drawn toward him; and, since the coming of Burnet, was more frequently in his wife’s company than he had been before.

Mary began to look forward to those hours as the most rewarding of her days. There she would sit working at the fringe close to the candles, to get the utmost light; Burnet would answer the questions she put to him and gradually a picture of the English Court would evolve. William would sit a little apart listening, now and then firing a question of his own, his head, looking enormous in its periwig drooping over his narrow shoulders and slightly hunched back, throwing a grotesque shadow on the wall.

It was the nearest to domesticity that Mary had ever reached; and she wanted to go on like this, for she believed that William was changing toward her since Burnet had come. While he was in her company he was neglecting Elizabeth. Perhaps he was finding that his wife could be of greater help to him in his political schemes than his mistress ever could be. So as she talked to Burnet she was deeply conscious of William; and she asked those questions which she thought would best please her husband.

As she talked William began to understand Mary more than ever before. She was not the foolish girl he had sometimes believed her to be, but a woman of intelligence and above all tolerance. William himself wanted tolerance … up to a point; and he appreciated this quality in his wife.

He listened to them discussing the preacher Jurieu who had written scurrilously of Mary Queen of Scots.

Mary offered the comment: “If what he had said was true, then he was not to blame. If Princes do ill things, they must expect that the world will take revenge on their memory since they cannot reach their persons.”

An unusual sentiment for a Princess to express, thought William. Yes, she was an unusual woman, this wife of his.

He watched her, stately, plump, her dark head bent slightly forward over the fringe. She was beautiful; and she was not without wisdom. He began to think that he had been rather fortunate in his marriage.

Never would he be able to explain to her his need of Elizabeth. Mary lacked that sexual appeal which he found in his mistress. He knew of that passionate friendship with Frances Apsley—not a physical passion that, yet it was an indication of Mary’s character. She could be firm and so very meek. She could love devotedly and at the same time had not that to offer which could make a perfect union between a man and woman.

Yet William himself was no virile man. He did not ask for great sexual passion. Mary’s docility, her willingness to find in him an ideal husband could have made him very contented with his marriage. There were only two things which stood between them: his absolute need of Elizabeth Villiers and his ignorance of what attitude she would take toward him if the throne of England were hers.

Burnet, watching them, decided that his future lay with them, guessed what plans were forming in the mind of the Prince of Orange, was aware of this gulf between them, and sought to discover what it was and if it could be bridged.

The friendship between these three grew.

For Mary it was delightful to see her husband sitting by the fire listening gravely to her and Gilbert as they talked and occasionally throwing in a remark. Not since Monmouth had gone had she felt so contented. The skirt of her dark velvet gown caressed the black and white tiles and the candlelight touched the red velvet of hangings, high windows, and painted ceiling with a light which made them more beautiful than by day. Every now and then she would close her eyes to rest them a little, or glance up from her fringe to one or other of the two men—to William so fragile under his enormous periwig, his hands as delicate as a girl’s; and Gilbert Burnet in great contrast in the black and white robes of the Church—a heavy man with coarse features illuminated by the light of a shrewd and clever mind.

The two men were bound by a common desire. They wanted James deposed and William and Mary reigning in his place, and were asking themselves, How can this be brought about without delay?

Mary talked of England too and of the days when there would be a new ruler; but the man these two wished so ruthlessly to depose was her father and it did not occur to her that when England was discussed, the future they talked of could be before her father’s death.

As the pleasant sessions continued, spies carried accounts of them to England.

James wrote to William: It was unseemly, he declared, that his enemy should be treated as a close friend of the Prince and Princess of Orange.

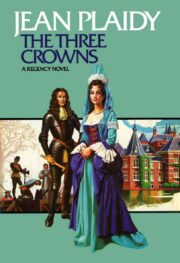

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.