“I should want to prove them guilty first.”

“It should not be difficult. Others will be in it. Leave it to me. I’ll find out.”

He kissed her. He could trust her he knew, his clever Elizabeth.

In a few days she had the answer.

“It is more serious than we believed. James is behind this.”

“James? But how?”

“His idea is to have your marriage annulled so that Mary can make a marriage more to his liking.”

“A Catholic marriage!”

“That is exactly what he would like. Whether the people of England would accept that is another matter. In any case, James does not want you to remain his son-in-law. Covell is an old fool … fortunately. He cannot keep his mouth shut. He’s delighted to be working with Skelton who has his orders straight from Whitehall. You see the nature of our little plot?”

“You’re a clever girl, Elizabeth.”

“Have you only just discovered it?”

“I always knew it.”

“I am glad, for the more clever I am the greater service I can offer my Prince.”

She took the frail little hand and kissed it. She expressed herself charmingly; her gestures were delightful.

I’ll never give her up, he thought. I’ll defy James and all England if necessary; and I’ll keep Elizabeth … and Mary.

The Prince of Orange was out hunting but his thoughts were not on his quarry. They were back at the Palace where he had given instructions to a few trusted servants to keep watch for anyone leaving with letters.

These were to be stopped and searched, and any letters found on them were to be subjected to scrutiny.

The stratagem worked.

When he returned to the Palace several letters from Covell to Skelton and from Skelton to his master were laid before him.

In these it was quite clear that a plot was in progress to bring about the dissolution of the Orange marriage. The Princess was first to be made aware of her husband’s infidelity with Elizabeth Villiers, then to be made to see she could not condone it. The names of Anne Trelawny and the Langfords were mentioned.

William, having read the letters, sent for Covell.

There was nothing brave about Covell, and William in a cold rage could be intimidating.

“Do you admit that you have been plotting against me?” demanded William.

Dr. Covell, seeing that he could not deny it considering William was holding his letter in his hand, confessed that this was so. He told him that he was acting on instructions from Skelton, who had received his orders from Whitehall.

“Get out,” said William.

When he had gone he sent for Mary.

She came in fear. He studied her coldly for some seconds before speaking.

Then he said: “I can only believe that you are so stupid that you do not understand you have been the victim of a conspiracy.”

“I … William?”

Now she was like the Mary he knew, meek and frightened of him.

“Yes, you. Your father has decided to marry you to a Papist.”

She gasped in horror. “But I am married to you, William.”

“He does not intend you to remain so.”

“But how could I …?”

He lifted a hand to silence her. “You have been very weak. You have listened to gossip and believed the worst of me. In so doing you have played into their hands. Your father is a ruthless man. Have you forgotten Monmouth and the Bloody Assizes? Your father is to blame for those tragedies, and now he wants to add another to their number.”

“He has had to defend his crown, William.”

“So you make excuses for him?”

“He is my father.”

“I wonder you are not ashamed to call him so.”

“I know that he is mistaken so often in what he does. But it is true, William, that Elizabeth Villiers is your mistress.”

A quiver of alarm touched him. That vein of strength in her was apt to appear when he believed he had subdued her, to make him never quite sure of her.

He felt a stirring of panic and said quickly: “She is nothing to me.”

“William!”

“But …”

He would not let her speak, lest she ask questions he could not parry. He had heard the note of joy in her voice. She wanted Elizabeth Villiers to be of no importance to him. She was willing to meet him halfway.

“Why,” he said, “have you forgotten that you are my wife?”

“I feared you had forgotten it, William.”

“It is something I could never forget.” That was true enough. Was she not the heir to the three crowns he coveted? “So let us be sensible, Mary.”

“Yes, William.”

“This affair … it was nothing. It meant little to me.”

“And it is over?”

“I will never forget that you are my wife. Our marriage is important … to us … to Holland … to England. We have our duty. Let us never forget that.”

“No, William.”

He put his hands on her shouders and gave her his wintry smile. He saw the tears in her eyes and knew that he had won.

When she had gone he sent for Covell, Anne Trelawny, and the Langfords.

“You should begin your preparations,” he said. “You leave for England tomorrow.”

Then he sat down and wrote to Laurence Hyde—the King’s brother-in-law—and asked that Skelton be recalled and another envoy sent to Holland in his place.

Mary was saddened by the loss of her dear friends. She had particularly loved Anne Trelawny and when she remembered how they had been allies in the days of Elizabeth Villiers’s ascendancy in the nursery she felt her departure the more.

For it was useless to pretend Elizabeth was not William’s mistress. William had said that the affair was of little importance, but he continued it. Elizabeth Villiers seemed slyer and more smug than ever; and now that Mary had been forced to face the truth she could not get it out of her mind.

Why should she endure this? When William was absent she felt very bold; it was only when he was with her that she told herself she must reconcile herself to her fate.

William had left The Hague for a short visit inland on official business—actually so this time, for Elizabeth Villiers remained in the palace.

Why should I stand aside while they conduct this intrigue under the very same roof? Mary asked herself. They think that I acted as I did because Anne Trelawny and Mrs. Langford advised me to. They think I have no will of my own.

They were wrong. Although she longed for ideal relationships, for peace between her father and her husband, she was not afraid to assert her will when she thought it necessary to do so; she would show them this.

She sent for Elizabeth Villiers.

Elizabeth stood before her—sly, always sly, and alert, wondering with what she was about to be confronted.

“I want a very special and important message to be delivered,” said Mary, and her regal manner alarmed Elizabeth.

“Yes, Your Highness.”

“Knowing your discretion and intelligence I am giving you the task of delivering it.”

“Your Highness can be assured that I shall obey you to the best of my ability.”

“I am sure you will do well what you must.”

Mary went to her table and picked up a letter which was sealed with her royal seal. A great deal of thought had gone into writing that letter.

“You should leave at once,” she said; and as she turned to look at her enemy a fierce jealousy struck at her. What had Elizabeth to offer him? She was clever; no one doubted that. But as far as beauty was concerned she was not to be compared with Mary who had been called one of the most beautiful women in Europe, and although royalty was always given more credit for beauty than it deserved, that opinion was not all flattery. It was true that she had put on too much weight but her hair was still abundant, her dark shortsighted eyes, although they were giving her a great deal of trouble, were still attractive.

And there was Elizabeth with that extraordinary cast; perhaps that was attractive, that, and her wit and her boldness.

“To whom is the message to be delivered, Your Highness?” asked Elizabeth.

“To my father.”

It gave Mary pleasure to see the start of amazement quickly followed by panic.

“I beg Your Highness’s pardon but … did I understand …”

“You understood very well,” said Mary. “You surely do not imagine that I would ask you to deliver an ordinary message … like a page?”

“No, but …”

“I wish you to leave within the hour. You will be taken to the coast where a ship will be found for you. I trust you will have an easy crossing.”

Mary was sure that never in her life had Elizabeth Villiers been so bewildered. Quite clearly she did not know what to say. William was away from The Hague therefore she could not appeal to him, and in his absence, Mary’s orders must be obeyed without question.

Two of Mary’s male servants came into the room as they had obviously been commanded to.

“Everything is ready,” Mary told them. “You will leave immediately.”

Nonplussed, Elizabeth could do nothing but follow them; Mary stood at her window watching the departure.

Now all she had to do was await the return of William.

William was back at The Hague for two days before he discovered Elizabeth’s absence.

It was Bentinck who told him. The quarrel between them had been mended, and although William had not apologized—that would have been asking too much—he had implied he was no longer displeased, while at the same time he wanted his friend to know that while he respected his advice on matters of state he wanted no interference with his domestic affairs.

“My sister-in-law has left for England,” Bentinck said.

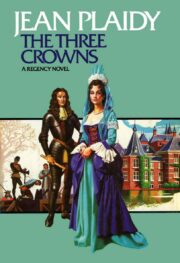

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.