“Anne, you are becoming hysterical.”

“I feel hysterical. I have to stand by and see your life ruined. You might have dear little children by now. But how can you? He is never with you … or hardly ever. Something will have to be done.”

Mary called Mrs. Langford. She said: “Help Anne to her bed. I fear she is not well.”

Mrs. Langford came to Mary.

“Your Highness,” she said sorrowfully, “Anne Trelawny has told me what she said and she is afraid you are angry with her. She said it only out of her love for you.”

“I know.”

“Oh, my lady, my dear little lady, it’s true.”

“I do not wish to hear the subject mentioned again.”

“My lady, I’ve nursed you since you were little. I know you are a Princess but you will always be my baby.” Mrs. Langford began to cry. “I cannot bear to see you treated in this way.”

“There is no need for you to be sorry for me.”

“You don’t believe it, do you? You don’t believe he goes to her bed … almost every night. You don’t believe that when he tells you he has state matters to deal with he is there. She is his state matter, the sly squint-eyed whore.”

“You forget yourself.…”

“Oh, my little love, forgive me. But I cannot endure much more of this. Something should be done.”

Mary was silent. It was true. She had always known it. For years she had known it and pretended. No one had ever mentioned it and that had made it easy to live in a world of make-believe. But now they had drawn aside the veil of fantasy and there was the unpleasant and unavoidable truth to be faced.

“You don’t believe it, do you, my Princess?” went on Mrs. Langford. “It wouldn’t be so difficult to prove. They’ve got careless over the years. Over the years! Years of deceit. Think of it. And you longing for babies!”

Years of deceit! thought Mary.

She closed her eyes and saw the little boy who had come to her table to steal sweetmeats. Jemmy had noticed—so had others. They had been sorry for her; and many of them would have said: How she longs for a child; but she is barren. Some say the Prince is impotent. Others that he spends too much time with his squint-eyed mistress.

Hundreds of pictures from the past crowded into her mind. Elizabeth in the nursery—sly hurtful remarks … always making her uncomfortable … an enemy.

And now, William loved her. What was the use of hiding the truth. What was the use of pretending that William was a noble hero when everyone knew he was committing adultery under the same roof as that which sheltered his wife.

Perhaps they were right. Perhaps it was time something was done.

She spent a sleepless night and in the morning she told herself that she must ignore these whispers. She must speak severely to Mrs. Langford and Anne Trelawny.

But it was not easy.

“You don’t believe us,” said Mrs. Langford sadly.

Anne, that dear friend whom she knew had always loved her since their childhood, was bolder. “Your Highness does not want to believe,” she said, “and that is why you will not put us to the test.”

“Put you to the test?”

“Yes. Make sure that we are speaking the truth.”

“How?”

“He goes to her apartment almost every night. You could wait for him to leave it.”

She shook her head.

But she went on thinking about William and Elizabeth. She pictured him, slyly mounting the stairs to the maid of honor’s room, opening the door, Elizabeth waiting … the embrace. Sly Elizabeth! Cold William! What was this attraction between them? Were they laughing at her for being so simple that she had not discovered their deceit?

The card game was over. Mary said that she was tired and would retire to her room.

She smiled at the Prince, who although he did not play cards, had joined the assembly.

“You are looking tired,” she told him. “Could you not desert your work for one night and retire early?”

He looked at her coldly and replied that urgent dispatches were awaiting his attention.

“You work too hard,” she said, smiling fondly, and bade him goodnight.

Her ladies prepared her for bed and she dismissed them all except Anne Trelawny and Mrs. Langford. Then Anne brought a robe and wrapped it about her.

“It may well be that you will have to wait a long time at the foot of the privy stairs to the maids of honors’ apartments,” she said.

“I shall wait,” said Mary firmly.

They made her comfortable there.

They knew that he was visiting Elizabeth Villiers that night because Mrs. Langford’s son had been set to wait behind the hangings and he had seen him go to her.

Only Mary’s anger saved her from tears.

They had successfully convinced her that she had allowed herself to become an object of pity since, it seemed, all knew of the adulterous intrigue except herself.

William looked down at Elizabeth who yawned sleepily as she smiled up at him. She implied that she was utterly contented.

He felt rejuvenated, as he always did after these occasions. She attracted him as no other woman ever could. He did not know exactly what it was; she was knowledgeable, dignified, and without a trace of humility, which surprised him for he had always thought that docility was what he would ask in a woman, but she was so eager to be all that he wanted, he was deeply aware of that and it flattered him. She kept in step with him on state affairs and he guessed that must have been a great task; she was not afraid to offer an opinion. She was sensual but never over demanding; she seemed to be able to assess his strength to the smallest degree. She had made him her life, and she flattered him without seeming to do so. He would not have known what he wanted of a woman until he met Elizabeth and she had shown him.

He could never break with her, however much the intrigue worried his Calvinistic soul. He told himself that she was a necessity to him. She supplied the recreation he needed; with his frail body and active mind, he needed that relaxation and only she could give it. That was his excuse; and he would scheme and lie to keep her.

Sleek as a satisfied cat she watched him, delighted with the part she was called upon to play. The power behind the throne! She could not have asked for a more exciting role. She was no longer jealous of foolish sentimental Mary as she had been in the nursery days and she could always hug herself with delight to consider their positions now.

William shut the door gently and cautiously descended the privy stairs.

As he reached the last step a figure rose before him. He stared, unable to believe in those first seconds that it was his wife.

“Yes,” she said. “It is I.”

“What are you doing here?”

“Waiting for you to finish dealing with those … state papers. I did not know that you kept them in Elizabeth Villiers’s bedchamber.”

“This is most unseemly.”

“I agree. The Prince of Orange tiptoeing from his mistress’s bedroom!”

“I do not wish to hear another word about this.”

“I do not suppose you do. But I wish to speak of it.”

“You are behaving even more foolishly than usual.”

“And, William, how are you behaving?”

“With great restraint, I assure you.”

“William …”

He pushed aside her arm.

“Go back to your apartments. I am most displeased with you. I should have thought you would have had more dignity than to behave like a cottage shrew.”

“And your behavior …” But her voice had faltered, he noticed, and he seized the advantage.

“I am more than displeased by your conduct,” he said. “I am very angry. I do not wish to see you or speak to you until you are in a more controlled and reasonable state of mind.”

With that he left her standing there, forlorn and tearful.

Anne Trelawny and Mrs. Langford, who had been listening, came out to take her to her bed.

They looked at each other in exasperation. One would have thought that she was the sinner. Oh, it was indeed time she had a kind and loving husband.

They got her to bed and she lay shivering and sleepless.

For some days William avoided her but he was very uneasy.

He sent for Bentinck as he did when he was perplexed, and told him what had happened.

“Someone must have advised her to do this. I suspect that girl Trelawny. I am going to find out, and if she is guilty she shall go back to England.”

“It’s a little harsh on the Princess,” suggested Bentinck.

“I don’t understand.”

“Your Highness was visiting my sister-in-law. She is your mistress. The Princess would naturally be disturbed to discover this!”

“And you think it right and fitting for her servants to help her to spy on me?”

“I think it a very natural state of affairs,” said Bentinck.

“There are times, my friend, when you exceed your duty.”

“I had believed that Your Highness always wanted me to answer your questions truthfully.”

“I do not want insolence … even from my friends.”

“I would respectfully point out that there was no insolence in my reply.”

“You are being insolent now. You may go, Bentinck. I no longer need your presence.”

As Bentinck bowed and retired, William stared at the closed door in dismay. This was the first time he had ever quarreled with Bentinck; he could scarcely believe it had happened.

First to be discovered in that undignified way by a wife waiting at the bottom of a staircase! Then to be told he was in the wrong by one whose friendship he valued!

He was ashamed, and when he was ashamed he was angry.

Elizabeth opened very wide those eyes with the—to him—enchanting cast and said: “It is simple. Anne Trelawny and the Langford woman are at the bottom of this. They are always whispering together. Get rid of them and everything will be well.”

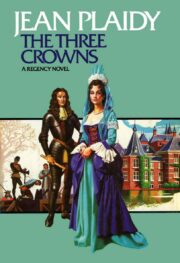

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.