“I have only time to tell you that it has pleased God Almighty to take out of this world the King my brother. You will from others have an account of what distemper he died of; and that all the usual ceremonies were performed this day in proclaiming me King in the city and other parts. I must end, which I do, with assuring you, you shall find me as kind as you can expect.”

As kind as you can expect. There was an ominous ring in those words.

Great events were about to break and rarely had William felt so excited in the whole of his life.

When Skelton was ushered in he came straight to the point. “His Majesty King James II wishes you to send the Duke of Monmouth back to England without delay.”

William bowed his head. “I shall do as the King of England demands. And now if you will leave me I will have him informed that he is no longer my guest. Then, when that is done, you may make him your prisoner and conduct him to your master.”

Skelton was delighted with his easy victory; but when he was alone William immediately sent a messenger to Monmouth with money, explaining that a plot was afoot to carry him back to England and his only hope was to leave Holland with all speed.

Thus when Skelton went to arrest Monmouth, he had fled.

Gone were the gay and happy days.

Mary sat with her women thinking of the dances and the skating, wondering what the future would hold.

All through the spring she waited to hear news of Jemmy. There was none.

He will never be able to return to England because my father hates him, she thought.

But in May of that year there was news. Monmouth had left for England.

The tension at The Hague had never been so great. Messengers were arriving at the Palace all day. William was shut up with Bentinck for hours at a time; he hardly seemed to be aware of Mary.

Monmouth was in Somerset. Taunton was greeting him. He had followers in the West of England who would go with him to death if need be for the sake of the Protestant cause.

To William’s surprise there were many to support the King, and his army under Churchill and Feversham was a well-trained force. What chance had the rebels against it?

King Monmouth, they were calling the Duke. King! William gritted his teeth and prayed for the victory of his greatest enemy.

It came with Sedgemoor and debacle. Victory for King James. Defeat, utter and complete, for King Monmouth.

In The Hague William secretly rejoiced. Monmouth, you fool! he thought. You deserve to lose your head and you will, King Monmouth.

Oh, Jemmy, thought Mary, what will become of you? Why did you do this? Why could you not have stayed with us, dancing, skating. We were so happy. And now what will become of you?

She quickly learned. Before the end of July Jemmy was dead. He was taken to the scaffold from his prison in the Tower. He went to his death with dignity and he did not flinch when he laid his head on the block.

THE WIFE AND THE MISTRESS

Those months stood out forever in Mary’s memory; they were the turning point in her life. Jemmy was dead … killed, on her father’s order.

“He was his uncle,” she said stonily to Anne Trelawny.

“Monmouth was a traitor, Your Highness.”

“I do not believe he meant to take the throne.”

“Your Highness was always one to believe the best of your friends. He called himself King Monmouth. He could not have been more explicit.”

“Others called him that.”

She could not be comforted. She shut herself in her apartments and thought of him—dancing, laughing—making love with numerous women. He was no saint. He was not a noble honorable man such as her husband was. But he was so beautiful, so charming, and she had never been so happy as when in his company—except of course on those occasions when William showed his approval of her.

If he had never come to The Hague, she thought, I should not be mourning him so bitterly now.

The entire Court was talking of what was called the Bloody Assizes which had followed Monmouth’s defeat at Sedgemoor. They spoke in shocked whispers of the terrible sentences which were passed on those who had rebelled against the new King of England. Death, slavery, whipping, imprisonment. It was a tale of horror.

And this, said Mary, is done in the name of my father.

Dr. Covell, who had succeeded Dr. Kenn as chaplain to the Princess of Orange was flattered to receive a call from Bevil Skelton the English Envoy at The Hague.

Skelton implied that he wished to speak to Covell alone and when he came into the chaplain’s apartment there was an air of secrecy about him which delighted Covell. Covell, an old man, who lacked the courage and personality of Hooper and Kenn, his two predecessors, guessed that some highly confidential matter was about to be communicated to him.

He was right.

“Dr. Covell,” began Skelton, “I know that I can rely on your discretion.”

“Absolutely, my dear sir. Absolutely.”

“That is well, because I am going to take you into my confidence regarding a very secret matter.”

“You may have the utmost trust in me.”

“I believe,” said Skelton, “that you deplore the way in which the Prince treats our Princess.”

“Scandalous, sir. Quite scandalous.”

“And you are a faithful servant of King James II, our lawful sovereign.”

“God save the King!”

“I must insist that you keep this absolutely to yourself.”

“I give my word as a priest.”

“Well, then, this Orange marriage is not satisfactory. Not only is it without fruit but the Princess is treated like a slave. His Majesty knows this; the Princess is his favorite daughter and he is deeply concerned. It is clear that she is unhappy. She must be unhappy. No wife could be otherwise, neglected as she is. The King wishes to have the marriage dissolved and it is my duty to find a way of doing it.”

Covell was too astonished to speak and Skelton went on: “Oh, I know you are thinking this is impossible. On the contrary it is not so. There is ample reason why this marriage should be dissolved.”

“You mean the Prince is incapable of getting a son?”

“I mean that he spends his nights with another woman.”

“I understand.”

“The Princess does not seem aware of this.”

“The Princess is not always easy to understand. At times she seems almost childlike; at others her control is astonishing and one feels that she is very wise indeed.”

“I believe that if she were made aware of what is going on behind her back her pride would be wounded. She is a proud woman. Remember she is a Princess. Our first step should be to make sure that she is aware that her husband has a mistress to whom he must be devoted considering she has occupied that position since she came into Holland.”

“Do you wish me to tell the Princess?”

“We must be subtle. Have a word with her women—those you feel will be most likely to put the case to her … as it should be put. I should not ask either of the Villiers sisters to betray the elder one.”

Covell nodded. Skelton was referring to Anne Bentinck and Katherine Villiers, who had married the Marquis de Puissars, and were both in Mary’s service.

“I will have a word with Anne Trelawny,” said Covell. “She loves her mistress dearly and I feel sure she hates the Prince almost as much as His Majesty does.”

“I see you have the right idea,” said Skelton. “Now … let us go into action without delay.”

Covell, who enjoyed intrigue and liked to think he was not too old to indulge in it, immediately sought out Anne Trelawny and as Mrs. Langford was with her, and he knew that lady to be as fiercely against the Prince of Orange as the other, he decided to take them both into his confidence.

He explained the nature of the plot and there was at once no doubt that he would have the assistance of these two.

“I have always said it was monstrous!” declared Mrs. Langford. “My Princess ignored for Squinting Betty!”

“What he sees in her, I can’t imagine,” added Anne. “When I think of my beautiful Lady Mary …”

“See if you can bring what is happening to her notice,” said Covell.

“It should not be difficult,” said Mrs. Langford.

“Sometimes,” added Anne, “I wonder whether she knows and pretends it is not so. That would be like her. I am sure she is too clever not to have discovered it. After all it’s been going on long enough.”

“I don’t know, Squint-eye is clever. Have you noticed since we have been in Holland and she’s been playing the whore how retiring she’s been. She’s never given the Princess any cause to complain about her. Whereas before …”

“Never mind,” said Anne, “the Princess is going to know now.”

Anne was dressing Mary’s hair and Mary said: “You are preoccupied, Anne. Is anything wrong?”

Anne stood still biting her lip. In apprehension Mary glanced at her body, remembering the case of Jane Wroth. Not Anne, surely!

Anne said: “I … cannot speak of it.”

“Nonsense. Not tell me! Come! Out with it.”

“Oh, I get so angry. It is Elizabeth Villiers. How dare she … deceive Your Highness so … and glory in it. There, I’ve said it. It’s been on the tip of my tongue these last six years. Six years! It’s no wonder …”

Mary had turned pale. That which she had forced herself to ignore and refuse to accept was now being thrust at her; and it was a hateful realization that she could not ignore it any longer.

“What are you saying, Anne?”

“What I should have said before. Your Highness does not know. They are so sly. But I hate … hate … hate to see it, and I can’t keep silent any longer.”

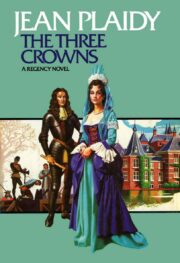

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.