Then more severely: William is the idealist. He would never have indulged in all the pranks Jemmy indulged in. Jemmy was wild in his youth as William would never be. Jemmy might be handsome and charming but it was William who was the great leader.

She thought of Jemmy’s wild past, how again and again his father had stepped in to save him from disgrace and disaster. She remembered poor Eleanor Needham who had left court when she was seduced by him and about to bear his child. Now she had five of his children; the Duchess had six and Henrietta two. Thirteen children that she knew of and there were probably others—and she had not one. How could she possibly compare William and Jemmy!

There was Elizabeth Villiers.… She shut her mind to that affair. She saw Elizabeth frequently but she had convinced herself that that trouble was over. William had too much with which to occupy himself; he simply had not time for a mistress. It was over. It was to be forgotten.

She was dining in public nowadays which was something she had not done for a long time. William no longer wished her to live like a recluse, and he was always anxious that people should know that they were in accord.

One day while she sat at table a dish of sweetmeats was placed before her and as she looked at them idly she saw a small fat hand descend on the dish and pick up handfuls of the sweetmeats.

She gasped with surprise and a pair of blue eyes were lifted to her in fear. They belonged to a small boy who had seen the sweetmeats placed there and had found them irresistible.

“Your Highness, I pray you forgive him …” The boy’s terrified nurse had seized him; she was trying to hold him and stay on her knees at the same time.

Mary smiled. “Come here, my child,” she said.

The boy came.

“So you wanted the sweetmeats?”

He nodded. “They are very nice.”

“How do you know until you have tried them? Come, sit here beside me and eat one now.”

He looked a little suspicious until Mary signed to the nurse to rise. Then the boy sat down and ate one of the sweets.

“Is it good?” asked Mary.

“It’s the sweetest sweetmeat I ever tasted.”

“Well, won’t you try another?”

He did, and Mary, watching the little round head with the flaxen hair, the golden lashes against a clear skin, felt a great emptiness in her life. If he were but my son! she thought.

She talked to the boy and he answered brightly while his nurse stood by marveling at the success of her charge; and when Mary reluctantly let him go she told him that whenever he wished for sweetmeats and saw them on her table he should present himself because she would prefer to give them to him than that he should attempt to steal them.

When she danced with Monmouth that evening, he having seen the incident with the child, said: “Mary, do not be too grieved that you have no children. You will … in time.”

She flushed. “Sometimes I think not, Jemmy.”

“But that is not the right attitude.”

She could not tell him that William rarely gave her an opportunity of having a child and that she had begun to fear that he was incapable of begetting one which would live. Perhaps Jemmy understood that though, for he was very worldly wise.

She always tried to make light of her misfortunes and she was now afraid that her treatment of the little boy that day had made many understand the void in her life and feel sorry for her.

“You who have so many should know. But I believe, Jemmy, that you often had them when you had no great wish to.”

“The perversity of life,” he remarked. “But, Mary, do not grieve for the children you never had … to please me.”

“There is little I would not do … to please you,” she said.

He pressed her hand and it was love she saw in his eyes. Her own responded.

Jemmy was devoted to Henrietta and she to William; but there was love between them for all that.

Monmouth had changed the dour Court of The Hague; he had changed Mary’s life. Often she wondered how she could ever go back to live as she had lived before—almost like a prisoner! Rising early, spending much time in prayer and with her chaplain, sewing or painting miniatures when her eyes permitted, being read to, and her greatest diversion of course—playing cards.

She wondered why William had allowed this change. Was it because he wanted to show the world that he allied himself with the Protestant cause? The troublous matter of the succession in England was in fact one of Catholic versus Protestant. Her father would never have been so unpopular if he had not shown himself to be a Catholic.

But whatever the reason, the change had come; and when in December Monmouth told her that he was returning to England for a secret visit to his father, she was melancholy.

“I will be back,” he told her. “Needs must. I am still an exile.”

So he and Henrietta returned to London that December; and Mary was melancholy, wondering when she would see them again.

It had been a bitterly cold January day and it looked as though it were going to be a hard winter. Mary had slipped back to the old routine, rising early and retiring early.

On this particular evening she had decided to retire early as she intended to be up at a very early hour that she might take communion. Anne Trelawny and Anne Villiers, who was now Anne Bentinck, were helping her to undress when a messenger came to the apartment.

The Princess is to come at once to the Prince’s chamber, was the order.

Anne Trelawny said indignantly: “The Princess has already retired.” Anne Trelawny, indignant because her mistress was not treated with the respect due to her, was often truculent to the Prince’s servants.

The messenger went away and came shortly afterward. “The Prince’s instructions. The Princess is to dress and go to his chamber at once.”

Even Anne Trelawny had to pass on such a message to her mistress and when she heard it Mary immediately dressed.

When she presented herself at her husband’s apartments she gave a cry of pleasure, for Monmouth was with him.

“You are back sooner than I had hoped,” she cried.

Monmouth embraced her.

“And how do you find events in England?”

“Much as before,” answered Monmouth. “Your father is determined to have my blood. My father is determined that he shan’t.”

“And so you are to stay with us for a while?”

“I throw myself on the hospitality of you and the Prince.”

“You are welcome,” put in William. He looked at his wife. “There should be a ball in honor of our guest,” he added.

She smiled happily.

This was a return to all that she had begun to miss so much.

Observers were astonished by the behavior of the Prince of Orange, in particular the French Ambassador, the Comte d’Avaux, who reported to his master, the King of France, that he and Monmouth stood for Protestantism. He did not know what they were plotting together, but it might well be that should Charles die they would make an attempt to put Mary on the throne.

Mary, he reported, was sternly Protestant, adhering to the Church of England; she was a woman he did not understand; she seemed to form no fast friendships with anyone about her; she was completely the dupe of the Prince. And yet she was not a stupid woman; one would have thought she had a mind of her own. In fact over the affaire Zuylestein she had shown she had. He was following events closely, for William was throwing her constantly into the society of the Duke of Monmouth, who had not a very good reputation.

Orange was determined to fête Monmouth; he had given him free access to his private cabinet at any time—a privilege accorded only to one other person, his faithful friend Bentinck. It was a strange state of affairs and the French ambassador could only guess that he wanted the world to know he stood firmly for Protestantism.

Meanwhile Mary and Monmouth were constantly together.

A frenzied excitement seemed to possess them both. He was thinking that if they had married him to Mary he would have realized his ambition and become King of England. She was happy as she used to be in those long-ago days at Richmond. She loved to dance, laugh, and chatter without wondering whether what she said would be considered stupid. With her cousin she could be carelessly gay, she could talk with abandon; she could laugh and sing and dance.

“Dear God,” she thought, “I am so happy.”

“There should be theatricals,” said Monmouth, “as there used to be in the old days.”

“I should love that!” cried Mary, and then wondered what William would say.

But William made no objection. “Let there be theatricals,” he said.

So they played together—she, Monmouth, and Henrietta. William was a spectator—aloof but coldly indulgent, sitting there close to the stage watching. She could not act freely when she thought of him there. But it was at his command.

Because of the hard frost there was skating, and Monmouth expressed his pleasure in the sport.

“The Princess should skate with you,” William said.

“But, William, I have never skated.”

“Then learn. I doubt not the Duke will teach you.”

“It will be a pleasure,” Monmouth told Mary.

And so it was, after the first misgivings. How she laughed as she leaned against him, iron pattens on her feet, her skirts tucked up above her knees. Many times she would have fallen, but Jemmy was always there to catch her.

The French Ambassador was horrified. A most undignified sight, he commented. The Princess of Orange would only have so demeaned herself at the command of her husband, he was sure.

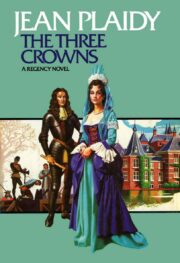

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.