William nodded. Charles did dote on this handsome son who was more than a little like himself. William thanked God that Charles’s sense of rightness had prevented him from giving his beloved son his dearest wish.

“My father and uncle were to be waylaid coming from the Newmarket races … and murdered. It was kept from me. I swear it, William, you know I would never harm my father.”

“I know it,” answered William.

“Russell, Algernon Sidney, and Essex are dead—Sidney and Russell on the scaffold, Essex in his prison—some say by his own hand. They wanted me to give evidence against them and I could not. They were my friends, even though they had kept me in ignorance of the plot to murder my father and uncle. And it is due to my father that I did not share their lot, William. It is due to him that I am here.”

“And what do you propose to do now?”

“What can I do? I cannot return to England.”

“Do you claim that your mother was married to your father?”

Their eyes met and Monmouth flinched. “I make no such claim,” he said, “for my father has denied it.”

William’s lips curled in a half smile.

“Then you can take refuge here. You will understand that I could not shelter one who put my wife’s claim in jeopardy.”

Monmouth bowed his head; he understood that he could rely on a refuge in Holland, but Mary must be recognized as the heir who would follow her father (or perhaps her uncle) to the throne.

William visited his wife in her apartments and at his approach her women, as always, promptly disappeared. Mary looked up eagerly and was dismayed to find herself comparing him with Monmouth. They were both her cousins—and how different they were! Monmouth, tall and dark with flashing eyes and gay smile. It was difficult to imagine William gay; his great wig seemed too cumbersome for his frail body and one had the impression that he would not be able to maintain its balance; his hooked nose, slightly twisted, seemed the more enormous because he was so small; he sat hunching his narrow shoulders, his small frail hands resting on the table.

“You realize the significance of Monmouth’s visit?” he asked coldly.

“Yes, William.”

Her face was alight with pleasure. She was always delighted when he discussed political matters with her.

“I think we must be watchful in our treatment of this young man.”

“You are as usual right, William.”

He bowed his head in assent. He was pleased with her; he was molding her the way he wanted her to go. She was beautiful too; her shortsighted eyes were soft and gentle; her features strong and good. He had always wanted a beautiful wife, but of course docility had counted more than beauty. In her he had both—or almost. When she stood up she towered over him; he could never quite forget her horror when she had learned she was to marry him; he could never forget his shuddering bride. He knew that she did not always agree with him but when she did not she bowed her head in tacit acceptance that it was a wife’s duty to obey her husband. On the other hand he must never forget the Zuylestein affair and that she was not the weak woman she sometimes gave the impression of being; on occasions she could be strong; and how could he ever be sure when one of those occasions would arise?

This made him cautious of her, and cold always.

“I have received a warning from Charles that I should not give him shelter here.”

She was alarmed. “We should not offend my uncle …” Then he was pleased to see that she realized her temerity in daring to tell him what he should do. She amended it. “Or William, what would be the best thing to do?”

“Monmouth shall have refuge here and I do not think in giving it we are going to offend our uncle. I will tell you something. When I was last in England he showed me a seal. He must have expected trouble with Monmouth—and indeed who would not? Your father is causing so much anxiety in England.”

She looked worried for it was almost as though William blamed her for her father’s misdeeds.

“He showed me this seal, and said: ‘It may be that at times I shall have to write to you about Monmouth. But unless I seal my letter with this seal do not take seriously what I tell you.’ ”

Mary caught her breath in wonder. “He must have a high opinion of you, William. And it so well deserved.”

He did not answer that, but added, “These instructions were not sealed with the King’s special seal; therefore we need not take them seriously.”

He half smiled; Mary laughed. She was so happy to share his confidences.

Mary was reading a letter from her father.

“It scandalizes all loyal people here to know how the Prince receives the Duke of Monmouth. Although you do not meddle in matters of state, in this affair you should talk to the Prince. The Prince may flatter himself as he pleases, the Duke of Monmouth will do his part to have a push with him for the crown, if he, the Duke of Monmouth, outlive the King and me. It will become you very well to speak to him of it.”

When Mary read that letter she realized how deep was the bitterness between her husband and her father. She wept a little. She so wanted them to be friends. If only she could make James understand how noble her husband was; if only she could make William see that for all his faults and aptitude for falling into trouble, her father was at heart a good man.

She went with it to William who, when he had read it, regarded her sternly.

“I see,” he said coldly, “that you are inclined to listen with credulity to your father.”

“William, he is a very uneasy man.”

“Let us hope he is. He should be, after his villainies.”

“William, he never intends to behave badly. He sincerely believes …”

William interrupted her. “Am I to understand that you are making excuses for your father?”

“I would wish that you could understand him.”

“I would wish that I had a wife of better sense.”

“But William, of late …”

“Of late I have tried to take you into my confidence. I can see that I have been mistaken.”

“No, William, you are never mistaken.”

He looked at her sharply. Was that irony? No, her smile was deprecating; she was begging to be taken back in favor.

He relented very slightly. “Because this man is your father you are inclined to see him as he is not. You should write to him and say that you can do nothing, for the Prince is your husband and your master and you are therefore obliged to obey him.”

“Yes, William,” she said meekly.

“In all things,” he added.

Monmouth was prepared to spend the winter at The Hague. James wrote furiously to his nephew; William ignored his letters; instead he gave orders to his wife.

“I wish you to entertain the Duke of Monmouth. There is no reason why we should not give a ball. Please see to it.”

Mary was delighted. A ball! It would be like old times. “Yet how shall we know the latest dances?” she cried. “But Jemmy will know them. I must have a new gown.”

William eyed her sardonically. She had not grown up as much as he had thought. Now she looked like that girl who had delighted him when he had first seen her—vivacious, gay, a typical Stuart, as he was not, perhaps because he was half Dutch. Mary was like her uncle Charles in some ways and to see her and Monmouth together made one realize the relationship between them.

They were two handsome people. Monmouth had always been startlingly attractive and so was Mary now that she was in good health and preparing to lead the kind of life she had enjoyed in England.

She was beginning to believe that this was one of the happiest times of her life. William was growing closer to her and allowing her to share confidences; she knew what was going on in England and every day there would be a conference between them. How she would have enjoyed these if her father’s name was not constantly brought into the discussions and she was expected to despise him! But since she was beginning to believe the stories she heard of her father’s follies, even that did not seem so bad.

Then there was Henrietta—what a dear friend she had become! Monmouth declared that she was his wife in the eyes of God and although Mary had loved the Duchess of Monmouth dearly, she had to accept Henrietta; for Henrietta was not the frivolous girl who had danced in Calista but was a serious woman with a deep purpose in life which was to give Monmouth all he desired and to live beside him for the rest of her life. Henrietta’s feelings for Monmouth were like those Mary held for William. They were two women determined to support their men.

Then there was Jemmy himself. It was impossible not to be gay in Jemmy’s company. Whatever great events were pending, Jemmy had always time to play. He could dance better than anyone else and he was very fond of his dear cousin, Mary.

She believed that he understood her feeling for William and that he was sorry for her. She did not resent pity from him because she was so fond of him, and because she felt so close to him that she could accept from him what she could not from almost anyone else.

There were times when his beauty and grace enchanted her; when she saw him and Henrietta together she found herself thinking that Henrietta must be the luckiest woman in the world. She looked forward to those evenings when Jemmy taught her the new dances.

“Do you remember Richmond?” she asked him.

And he smiled at her and said: “I shall never forget dancing with you at Richmond.”

Again she caught herself comparing William with Monmouth; and she stopped that at once.

They are so different! she assured herself. Each admirable in his way.

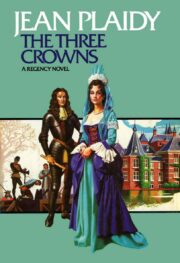

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.