“We bear what we must.”

“Is it necessary?”

“For a while James, yes.”

“Then I ask a favor … two favors. Let me go to Scotland where I have friends and where I can feel less of an outcast.”

Charles considered. “It could be arranged,” he said at length.

“And the other favor,” began James.

“I had hoped you had forgotten it. But let us hear what it is.”

“Should Monmouth stay in England while I am in exile?”

Charles looked at his brother wryly.

Reluctantly he agreed that he had a point there.

Monmouth would be sent abroad; and James would return to Brussels to collect his family and then go to Scotland.

Mary missed her family sadly and found it hard to settle down to life without them. William was as brusque as ever and she longed for him to show a little affection toward her. She excused him again and again to herself; he was noble, idealistic, she believed; naturally he had little time to fritter away with a wife when state affairs were such a concern to him. And she was a frivolous young woman who liked to dance, play cards, and playact.

He was unaware of her wistful glances but she began to build up a picture of him as a hero; he was the savior of his country; one day perhaps when she was older and wiser she would be able to share his counsels; that would be a goal to hope for.

There was something else which grieved her. Dr. Hooper and his wife, of whom she was very fond, returned to England. His stay had not been a comfortable one for William disliked him, mainly because he had persuaded Mary to remain faithful to the Church of England and not to join the Dutch Church.

It seemed to Mary when they left that not only had she lost the very dear members of her family but two good friends. In Dr. Hooper’s place came Thomas Kenn, a fiery little man who never hesitated to say what he meant and right from the first he expressed displeasure with William’s treatment of his wife. He was unkind and impolite, said Kenn. And that was no way in which to treat a Stuart Princess.

Mary wished that he would not call attention to William’s attitude when she was just beginning to make herself believe that the unsatisfactory state of her marriage was due to her own inadequacy. She wanted to make a hero of William; it was the only way in which she could find life endurable. She had to love someone because it was her nature to do so. Dear Frances, the beloved husband of fantasy, was so far away; besides, she had a real husband; in her imagination she was building William up into the hero figure, and people like Kenn with their caustic criticism did their best to destroy the dream.

There was another newcomer to The Hague. This was Henry Sidney who replaced Sir William Temple as British envoy; he was a very handsome man, the same who had been over-friendly with Mary’s mother and on account of this had been temporarily banished from the Court by James. Sidney was still unmarried, extraordinarily attractive, and in a very short time had become very friendly with William.

Mary had begun to suffer more alarming attacks of the ague and with the coming of winter these were more frequent, causing her to take to her bed.

During the cold weather she became so ill that she was not expected to live and there was consternation at The Hague. William saw his chances of the throne diminishing, for Anne and her children would stand in his way. In vain did he remind himself of Mrs. Tanner’s vision of the three crowns. But if Mary died how could he achieve them?

He visited her and sometimes she was aware of him.

“You must get well,” he said. “You must get well. What shall I do without you?”

Those words were like a refrain in her mind. Had she not always known that he was no ordinary man? He loved her; he needed her; because he had not been able to show his affection she had believed it did not exist.

It was a thought which sustained her through those days and nights of semi-delirium. Sometimes she thought she was floating down the Thames in a barge from Windsor to Whitehall; at others she was acting with Jemmy, and Margaret Blagge was there crying because she had lost a diamond; sometimes she was standing at the threshold of a room looking on at Jemmy and a woman … or her father and a woman; she cried out her protests and someone put cool ointment on her head and soothed her with gentle words. Then she was writing to Frances. “Dear husband …” And it was not Frances who was reading but William who said: “Did you not understand? I loved you all the time. I am not a man to talk of love. Would you have me as your father … as Jemmy … ready to make love to any woman anywhere?”

“No … no,” she whispered. “I would have you as you are. I have been foolish. I did not understand. But I do now. I must get well. You said you needed me.”

She did begin to recover. The fits were less frequent; the spring was coming and the apartments were filled with sunshine. Flowers were laid on her bed.

“The Prince of Orange sent them from his own gardens.”

Her fingers caressed them. “They are wonderful,” she said, and told herself: “I must get well. I have grown up now. I understand what I could not before. I shall no longer irritate him by my tears and childishness. I shall try to be wise, to talk with him of his plans, of his ideals. I shall listen at first while I learn … but I will let him know how willing I am to learn.”

She saw a future in which they would sup together; and they would talk. He would tell her what he thought of certain ministers; perhaps there would be little conferences between them, with Bentinck sharing of course. She would have to accept Bentinck who rarely left his master’s side.

So she began to get better.

Anne Trelawny and Elizabeth Villiers were quarreling.

“I trust you will be a little more careful now that the Princess is so much better.”

“What I do is my affair,” replied Elizabeth Villiers.

“It would be very much the Princess’s affair if she knew you were sleeping with her husband.”

“Do you propose to tell her?”

“You know your secret is safe with me … if it is a secret. She doesn’t suspect. So innocent is she.”

“One would have thought having been brought up in her uncle’s Court she might have learned a little suspicion.”

“He is so … so …”

“Yes?” mocked Elizabeth. “Pray proceed. What, you will not? Are you afraid I shall tell him?”

“How do I know what you say to him in bed at night?”

“Well, rest assured I shall not tell you.”

“I beg of you do not tell the Princess either. That’s one thing I would ask of you, Elizabeth Villiers. For God’s sake don’t let the Princess know you are the Prince’s mistress.”

“And one thing I would ask of you, Anne Trelawny, is look to your own affairs, and keep your nose out of mine.”

Mary had meant to surprise them, to walk a little farther, to open the door quietly and say: “See how much better I am!”

She had paused by the door. She had heard them. Anne, loyal Anne, who had nursed her so devotedly, her best friend in Holland, and Elizabeth Villiers, the traitor.

She stood against the door, her hand on her heart which was beating irregularly and as though it would burst out of her body.

“Don’t let the Princess know you are the Prince’s mistress.”

Elizabeth Villiers! who had been the jarring influence in the nursery. And William loved her!

If it had been anyone else, it would have been bearable. But would it?

She had fallen in love with her image of William during those hazy days of illness. She had fought off the listlessness which could have carried her to death; she had wanted to live; she had fought for life, because she had wanted to be loved by a husband whom she could love; she wanted a happy family, a man whom she could admire and adore, children made in his image.

“What shall I do without you?”

She had heard that? Or had she imagined it?

He had said it, she was sure, and then he had gone to bed with Elizabeth Villiers.

Elizabeth was so much older than she was, so much wiser. How long had it been going on? From the beginning? When she had so disappointed him, had Elizabeth been there to console him? She remembered hearing that Elizabeth had had a lover. Was it true? A lover before William? She would not have been a silly shrinking virgin, frightened by the touch of a stranger.

Elizabeth … and William!

She did not know what to do. If she sent for Elizabeth and accused her of being a harlot, what would William say? He would despise her more than ever.

Something had happened during that illness. She had fallen in love with an ideal husband who did not exist and she had fallen out of childhood.

She must remember that she was a woman now; she was royal. Princesses and Queens did not make scenes with their husband’s mistresses unless of course they could banish them from Court, which she could not. She thought of poor little Mary Beatrice, who had been nothing more than a child when she had discovered that her husband still kept his mistresses. How she had wept and stormed! And what had James done? He had made vague promises which he had not kept; and he had avoided his wife because he hated scenes. William was different. She could picture the coldness with which he would receive her accusations.

She faced the truth. She was afraid of William—afraid of his coldness and anger. She had intended to melt that coldness with her own ardor; but Elizabeth Villiers had done that before her.

Strangely she did not weep.

She was grown up now; she had done with weeping; but she would keep herself under a rigid control; neither Anne Trelawny nor Elizabeth Villiers should know that she had overheard their words.

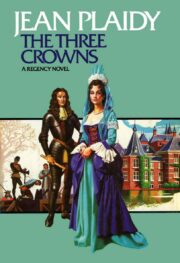

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.