She laid down her pen.

She pictured Frances reading the letter. It would make her smile; perhaps it would make her long for the companionship of her little “wife.”

It may be, thought Mary, that I shall never see her again.

When William heard of the pregnancy he was more pleased with Mary than he had been since the wedding; his smile was restrained but nevertheless it betrayed his pleasure.

“I trust,” he said, “that you will take every precaution for the sake of the child. I insist that you do. There must be no more dancing …” His lip curled distastefully. “No more games of hide-and-seek in the woods. It may well be that now you are to become a mother—and a mother of my heir—you will agree that it is beneath your dignity as Princess of Orange to indulge in such pastimes.”

Mary replied: “I wish you could have seen my father—who was a great Admiral—sitting on the floor playing ‘I love my love with an A’.”

“I consider myself fortunate to have been spared such a sight.”

Mary flushed and wished she had not spoken. He looked at her coldly and she was terrified that the tears would come to her eyes. The fact was that because she so fiercely tried to suppress them they came even more readily.

With others she could be the dignified Princess; with him she was the foolish child who wept when scolded or disappointed or afraid.

When the child is born, she promised herself, it will be different.

She wanted it to be different. She longed for him to smile at her, just once, in approval.

Mary was sitting with her women, painting a miniature while the others took it in turns to read aloud to her.

She was happier than she had been since she had heard she was to marry. When she had taken her exercise in the gardens that morning William had joined her; he had walked beside her, and her ladies had fallen into step behind them. He had said very little but then, of course, he never did; but he had looked at her not unkindly, a little anxiously, watching she guessed for some outward sign of pregnancy.

She had laughed aloud. “Oh, William, it is not noticeable yet.”

His mouth had tightened. He was shocked by open reference to a delicate matter. She knew he was asking himself what he could expect of one who had been brought up so close to the licentious English Court.

“I trust you are taking good care.”

“The greatest,” she answered fervently.

He glanced sideways at her and there was something in the look which pleased her. She knew that she was beautiful; her dark hair was abundant and she wore it after the fashion which was prevalent at Versailles—drawn away from her face with a thick dark curl hanging over her shoulder. It suited her; and her almond-shaped eyes were softer because they were myopic; her shortsightedness gave her a look of helplessness which was appealingly feminine. She was growing plump and her white shoulders were rounded. She had changed a good deal from the young girl he had brought to Holland.

But she seemed to displease him and she wondered why. She did not know that he could never forget her rejection of him in the beginning, that he was constantly wondering what would happen if she attained the throne, and whether she and the English would refuse to let him take precedence. That was very important to him. There was one other matter which disturbed him. As a husband he was deceiving her. He had taken a mistress from among her very maids of honor, and this troubled his Calvinistic soul; but he could not give up Elizabeth Villiers. He had believed it would be a brief affair—to be quickly forgotten; but this was not so. Elizabeth was no ordinary woman; she fascinated him completely. He talked to her of his ambitions and she listened; not only did she listen but she talked intelligently. She made it her affair to study that which was important to him. She was edging her way into his life so that he felt as strongly for her as he did for Bentinck. For the friend who had saved his life he had a passionate devotion; the strength of his feelings for the young man had on occasions alarmed him; that was another blessing Elizabeth had brought to him. She had shown him that while he was not a man who greatly needed women, he was a normal man.

He could not do without Elizabeth and every time he saw his wife he wished fervently that Elizabeth Villiers had been the heiress of England and the sentimental over-emotional young girl her maid of honor.

But now that his wife had conceived he need not often share her bed; and since she was clearly trying to please him he was disliking her less.

Once she had given him a son—a William of Orange like himself—there would be a bond between them and he would forgive her her childishness.

Yet his conscience disturbed him and for that reason he felt more critical of her; he was constantly looking for reasons why he should have taken a mistress. He had to justify himself not only to those who might guess his secret, but to himself.

But that morning in the gardens they had seemed to come a little closer.

She asked him to show her the part he had planned and he did so with a mild pleasure. She was ecstatic in her praise—too fulsome. He waved it aside and she said pleadingly: “William, after the child is born, may I plan a garden?”

“I see no harm in it,” was his gruff reply; but he was rather pleased to show her the crystal rose he had planted himself; and then he took her to the music tree.

The ladies exchanged glances.

“Caliban is a little more gracious today,” whispered Anne Trelawny.

“Caliban could never be gracious,” replied Lady Betty Selbourne. “He could only be a little less harsh.”

“My darling Princess. How does she endure it!” sighed Anne.

Elizabeth was aware of them and she was a little uneasy. When she became a mother Mary would inevitably become more adult; she was beautiful, something which Elizabeth never could be. But she was a little fool—an over-emotional, sentimental little fool, and Elizabeth Villiers assured herself she need never worry unduly about her.

Both Mary and Elizabeth were thinking of that morning in the gardens and neither were listening to the book.

Mary put a hand to her forehead and said suddenly: “This puts too big a tax on my eyes. Have done. I will walk in the gardens for a while.”

Anne Trelawny shut the book; Lady Betty took the miniature from her mistress and laid it on a table; and the Princess went to the window to look out on the garden, so green and promising on that bright April day.

But as she stood at the window she gave a sudden cry and doubled up with pain.

Anne Trelawny was at her side at once. “My lady …”

“I know not what is happening to me …” said Mary piteously, and she would have fallen to the floor had not Anne caught her.

She lay in bed, pale and exhausted. Throughout the Palace they were saying that she might die.

She had lost the child but she did not know this yet. No one could account for the tragedy, except that some perversity of fate often decreed it to be difficult for royal people who needed heirs to get them.

Her ladies waited on her, each wondering what the future held. Elizabeth Villiers could not stay in Holland if her mistress died. But could she? Was her position strong enough? She did not believe the Prince would lightly give her up. Jane Wroth was wondering what she would do if parted from Zuylestein; Anne Villiers was thinking of William Bentinck.

Only Anne Trelawny was wholeheartedly concerned with her mistress.

It is his fault, Anne told herself. He has never treated her well. He has neglected her and been cruel to her.

She went to Dr. Hooper, the Princess’s chaplain, and together they discussed the Prince’s cruel treatment of the Princess.

“It is his harshness which has made her ill,” insisted Anne. “Every day he makes her cry over something.”

“It is no way to treat a Stuart Princess,” agreed Dr. Hooper. “I doubt her father would allow this to go unremarked, if he knew.”

When Mary recovered a little the Prince came to see her. She looked at him apologetically from her pillows. His expression was cold and it was clear that he blamed her.

She had behaved with some lack of propriety; she had not taken enough care of this precious infant.

When he had gone Mary wept silently into her pillows.

William showed the letter he had received to Bentinck; and there was a cold anger in his eyes.

Bentinck read: “I was very sorry to find by the letters of this day from Holland that my daughter has miscarried; pray let her be carefuller of herself another time; I will write to her to the same purpose.”

Bentinck looked up at his friend. “His Grace of York?”

“Suggesting that I do not take care of his precious daughter. He is insolent. He never liked me. He was always against the marriage. A foolish man.”

“I am in agreement,” added Bentinck.

William’s eyes narrowed. “He grows more and more unpopular in England as he reveals himself as a papist.”

“The people of England will never accept a Catholic monarch.”

“Never,” said William. “Bentinck, what do you think will happen when Charles dies?”

“If the people of England will not accept James …”

“A papist! They won’t have a papist!”

“He is the rightful heir … the next in succession. The people of England want no papist … at least the majority do not … but they have a great feeling for law and order.”

William nodded. “Ah, well, we shall see. But in the meantime I do not care to receive instructions from my fool of a father-in-law.”

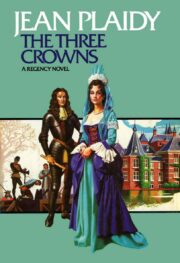

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.