“Good fortune!” cried Mary bitterly.

Lady Frances looked imploringly at the Prince. “Have I your permission to take the Princess to her apartments?”

The Prince inclined his head; and Lady Frances, greatly relieved, took Mary by the arm and led her away.

William looked after them; his cold expression was in contrast to the fierce anger which was burning in him. How dared she! Those red eyes, those sullen looks were there because she was to marry him! When he had last seen her, she had had no notion that she was to be betrothed to him, and therefore she had been gay and clearly happy. Then she had been told of her—as he believed—good fortune; and she had promptly wailed and moaned and, being completely undisciplined, had made it clear to all that she had no wish for the marriage.

What insolence! What childish tantrums! And this was the one they had given him for his wife!

He had an impulse to go at once to the King, to tell him that he had decided to return to Holland a bachelor. He wanted no reluctant bride.

Then he thought of those three crowns. To be King of Britain—well, was it not worth a little sacrifice.

Besides, she was a child; he would soon teach her the kind of conduct he expected in a wife. He must not jeopardize his future in a moment of pique over a spoilt child—especially as, after the marriage, he would have the whip hand.

No, he would marry this foolish child; and he would teach her who was master.

All the same his pride was hurt. She had made him see himself as he must appear to her—a man undersized, who stood awkwardly because his back had grown crooked, and wheezed a little because it was not always easy to breathe. Since the death of the de Wittes he had forgotten that image of himself. He had become a great leader, a man whom the King of England wished to please; he had ceased to think of himself as that pale young man who found it always necessary to assert himself.

She had brought back that image—that spoilt child!

He would show her.

Angrily he strode from the room and as he did so he almost collided with a young woman. He was brought up sharp and looked full into her face. She flushed and lowered her eyes, which he noticed were unusual; one seemed larger than the other and there was a cast in them. In his present mood the slight abnormality seemed to him attractive.

“I beg Your Highness’s gracious pardon,” she said.

The sound of her voice, humble, a little alarmed, soothed him.

“It is given,” he answered.

She lifted those strange eyes to his face and her look was one of recognizable adulation.

His lips moved slightly; it was not quite a smile, but then, he rarely smiled.

She passed on in one direction, he in another; then on impulse—strange with him—he turned to look after her at the very moment when she turned; for a second they gazed at each other; then she hurried away.

He found the memory of the girl with the unusual eyes coming between him and his anger with Mary. That girl had by a look and a few words restored a little of his lost pride. He wondered who she was; presumably she belonged to Mary’s suite; if so, he would see her again. He hoped so, for she had made quite an impression on him.

The Prince had made an impression on Elizabeth Villiers.

She knew what had taken place in the closet. How foolish Mary was! But Mary’s folly might well prove to the advantage of Elizabeth Villiers. She had been anxious. It was hardly likely that the Princess Mary would select her when she was in a position to choose her own household. Elizabeth Villiers would be no favored friend. But if not the friend of the Princess, why not the friend of the Prince?

Was she arriving at false conclusions, was she seeing life working out a certain way because that was what she wanted?

Well, that was a necessity which often occurred to an ambitious woman.

Mary, in her apartment, wept steadily throughout the day. Anne sat at her feet leaning her head against her sister’s knees crying with her.

Nothing could comfort either of them.

Elizabeth Villiers had been unexpectedly sympathetic to Mary; she did not attempt to persuade her to try to control her dislike of the marriage.

She was with her when, red-eyed, her body shaken by an occasional sob, Mary received the King’s Council and listened in silence to the congratulatory speeches.

The Prince of Orange was often present and although he gave no sign, he was very much aware of Elizabeth. In fact if she were not there he would have felt very angry but, by the very contrast to his betrothed, she made him feel less slighted by the insults Mary was giving him.

It was gratifying that through the country the news of the marriage was received with wild enthusiasm. The sky glowed with the reflection of hundreds of bonfires; although Mary Beatrice was pregnant and expected to give birth any day, not much hope was given to her producing a son and Mary was looked upon as the heiress to the throne. It was well, therefore, the people of England believed, that she was making a Protestant marriage.

The King was delighted with the people’s enthusiasm for the marriage. He told James that he should be, too.

“This is particularly important to you, James,” he reminded his brother. “You will see that people will not hate you quite so heartily when your daughter has married a Protestant. We’ll get this marriage made and consummated here on English soil before our bride and groom leave for Holland. You look ill-pleased.”

“I was thinking of Mary.”

Charles was momentarily downcast. “Poor Mary!” he said. “But peace, James … peace abroad and at home. Mary must do what is necessary for the sake of that.”

James was silent, thinking of his daughter’s unhappiness and the Prince of Orange whom he would never happily accept as a son-in-law.

The last day of freedom. A dull dreary day. Mist and cold outside the Palace of St. James; inside, dark foreboding.

Anne spent much of that day with her. Poor Anne, she was almost as wretched as her sister; and Mary tried to comfort her.

“We shall see each other often,” she told her.

“How?” asked Anne.

“You will come to Holland and I shall come to London.”

“Yes,” cried Anne. “We must. I could not bear it if we did not see each other very, very often.”

When they clung together Mary thought Anne seemed a little feverish. She mentioned this and Anne said: “It is because I am so unhappy at your leaving us, dear sister. And what shall I do while I am waiting to go to Holland and for you to come to England?”

“You will be at home,” Mary replied. “Think of me, far away in a strange land with a strange husband.”

And the thought of that calamity set the tears falling again.

Nine o’clock in the evening in the Palace of St. James. The hour of doom. In the bedchamber of the Princess Mary those who would participate in the ceremony had assembled. There was the bridegroom, pale and stern, gazing with distaste at the red eyes and swollen face of his bride. Henry Compton, the Bishop of London, had come to perform the ceremony and the Duke and Duchess of York had now entered with the King.

James’s eyes went at once to his daughter and he came to her side and embraced her.

“My dearest Mary,” he whispered, “my little one.”

“Father …?” she murmured and there was an appeal in her eyes.

“My dearest, if I could … I would.”

Mary saw that her stepmother, who was as round as a ball expecting as she was to end her pregnancy at any moment now, was trying not to weep.

“I shall miss you so much,” she whispered.

The King was approaching, and seeing the tears of the bride and her stepmother, the sullen looks of his brother, and the grim ones of the bridegroom, he was determined to make as merry an occasion of the wedding as was possible in the circumstances.

“Come now, Compton,” he said, “we are all impatient to be done with the necessary business.”

Charles laid a hand on Mary’s shoulder and pressed it affectionately. Poor child! he thought. But she would soon recover; she was a Stuart at heart and the Stuarts were gay by nature. Moreover, she was pretty enough to find herself someone who would please her as it was certain dour William would not.

He was sorry for her but he had long learned to feel emotions lightly, and while he was outwardly tender and kind to his sad little niece he was less concerned with her misery than anyone else at the melancholy wedding.

He looked slyly at William who, he knew, was hoping through this marriage to have the throne in time. An ambitious man, the bridegroom. Strange how big dreams often filled the hearts of little men.

“Come, Compton,” cried Charles, “make you haste or my dear sister the Duchess may give birth to a son before the ceremony is over and so disappoint the marriage!”

William’s expressions scarcely changed. He was becoming accustomed to his uncle’s sly witticisms.

William had placed a handful of gold and silver coins on the book as he promised to endow his bride with all his worldly goods. “Take it and put it into your pocket, niece,” whispered Charles, “for it is all clear gain.” The bridegroom had put the little ruby ring on her finger. The ceremony was over.

Mary stood shivering beside the man who was her husband. She was becoming more and more fearful, for the worst was yet to come.

The crowded room had been stifling hot in spite of the cold November air outside. Mary was bemused by the congratulations, the hot wine had gone to her head and she felt dizzy.

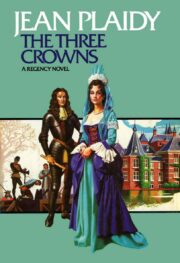

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.