And now the people were restive largely because they hated war. Charles would show them that he was prepared to put an end to the war and that he was no friend of the King of France because Louis would be furious at a match between Holland and England. Perhaps of late his subjects had begun to suspect Charles favored Catholicism.

“Very well,” said the King. “We will send for Orange. We will show the people that we are anxious for peace with Holland, for can we want to be at war with the husband of our own Princess Mary?”

“Your Majesty,” said Danby, “the Duke of York will not consent to this marriage.”

“You must make him understand the importance of it, Danby.”

“Your Majesty, the Duke of York has not your understanding of affairs. I feel sure he will remind us that you once promised not to dispose of his daughters without his consent.”

Charles was thoughtful. “It is true I made such a promise. But God’s fish, he must consent.”

Danby bowed his head. Consent or not, he thought, the marriage should take place. He, Danby, was rushing headlong to his ruin, as Clarendon had some years before. It was not easy to serve a King such as Charles II, a clever man who was in constant need of money and not too scrupulous as to how he acquired it, a man who was ready to conduct his own foreign policy in such a manner that his Parliament knew nothing about it.

For them both the marriage was a necessity.

Charles’s shrewd eyes met those of his statesman. He knew what Danby was thinking.

“You see the need as I do, Danby,” he said. “So, it shall be done. Tomorrow I leave for Newmarket.…”

James, furious, stormed into his brother’s apartments.

“I see you are speechless,” said Charles, “so I must help you out of your difficulty as I have so many times before by speaking for you. You have doubtless seen Danby.”

“This marriage …”

“Is most desirable.”

“With that Dutchman!”

“A dour young lover I will admit, but our nephew, brother. Forget not that.”

“I will never give my consent to this marriage, and I am her father.”

Charles raised his eyebrows and gazed sadly at his brother.

“Without my knowledge Danby has dared …”

“Poor Danby. He has his faults, I doubt it not … and many of them. All the more sad that he should be expected to carry those of others.”

“You promised that my daughters should never be given in marriage without my consent.”

“And, as ever, it grieves me to break a promise.”

“Then Your Majesty must be constantly grieved.”

“I fear so, James. I fear so. My dear brother, do try to be reasonable. This marriage must take place. It is more necessary to you than to any of us.”

“To me! You know I dislike that Dutchman.”

“He is of our flesh and blood, James, and we loved his mother. Families should live in amity together. He is a dull fellow, I’ll be ready to swear, but he did once try to get at the maids of honor.”

James shrugged impatiently.

“And you, James,” went on Charles, “are far from popular. This ostentatious popery of yours is a constant irritant.”

“And what of yourself?”

“I said ostentatious popery. You should learn to show proper respect to words, James, if not to your King. Now listen to me. If Mary marries our Calvinist the people will say: How can the Duke of York be such a papist if he allows this Protestant marriage! You need this Protestant marriage more than any of us.”

“Your Majesty has always been for tolerance.”

“I am more tolerant than my subjects are prepared to be. You have always known that.”

“And Charles, is it not your dealings with the French which make you so eager for this marriage?”

Charles smiled wryly. “As I have said before, I have no wish to be like a grand signor with mutes about him and a bag of bowstrings to strangle men if I have a mind to it. At the same time I could not feel myself to be a King while a company of fellows are looking into all I do and examining my accounts. There, James. That is your brother and King. Tolerance, yes. Let every man worship as he pleases and let the next fellow do likewise. Thus if I wish to be a papist I’d say I’ll be one and that is my affair. And if I make agreements with foreign kings because by so doing I can get what my Parliament denies me—well then, that is my affair too.”

“And because of this my daughter must marry the Dutchman?”

“Because of this, James—my follies, your follies, and the follies of those who want to go to war when they could live so much happier in peace. You’ll give your consent, James. Then … we must see that we get the better of our little Dutchman.”

When William arrived at Newmarket the King greeted him cordially.

“It is long since we met, nephew, too long. And now you come as a hasty lover.”

“I would wish first to have a sight of the Princess Mary,” replied William cautiously.

Charles laughed. “Do you think that we would ask you to make an offer for what you have not seen? Not a bit of it. You shall see her and I will tell you this: there is not a more charming young girl at this Court, nor in the length and breadth of England I’ll dare swear—perhaps not in Holland!”

William did not smile. He knew that they would attempt to make fun of him as they had before; he had always suspected that Charles had played a part in the maids of honor episode.

“I shall be delighted to meet her.”

“And in the meantime, my dear nephew, we will discuss less agreeable matters. We will save the tasty tidbit until the last which I believe is a very good habit. There are the peace terms which I suppose we should consider of the utmost importance. We will go into council here at Newmarket, and then it may be that there will be two great events to be celebrated.”

William’s lips were tight as he said: “Your Majesty, I could only discuss the terms of peace after the Princess Mary was affianced to me.”

“Oh come, nephew—business before pleasure you know.”

“I can do no more than explain to Your Majesty my intentions.”

Charles showed no sign of annoyance.

“What did I say,” he appealed to his friends. “Here we see the eager lover.”

The Lady Frances Villiers sent for the Princess Mary. She was fond of the Princess and yet relieved that very soon she would not be in charge of her. Mary had always been eager to please and gave little trouble; her passionate friendship with Frances Apsley was the only real anxiety she had felt on her behalf; and now there would be no need to worry about that.

“My lady,” said Lady Frances, “your cousin, the Prince of Orange, has come to Court and His Majesty is anxious for you and your sister to be presented to him.”

“I heard that he was in England,” replied Mary lightly. She was wondering whether Sarah Jennings would show her a new seal she had. It would be amusing to use it for her letter to Frances.

“Tomorrow you and your sister will be presented. The King and your father wish him to find you agreeable.”

Mary wrinkled her brows. “I have heard that he himself is not always considered so.”

“Who said this to you?”

Mary lifted her shoulders; she would be careful not to betray the offender. Lady Frances, who knew her well, was also aware that Mary had no realization of the reason behind her cousin’s visit.

Poor child, thought Lady Frances. She will have a great shock, I fear.

Mary was pleasant enough to look at, thought Lady Frances. She was trying to see the child with the eyes of a stranger and a would-be lover at that. She would most surely please him. Her complexion was unusually good; her nose well proportioned and her almond-shaped eyes really beautiful. She scarcely looked marriageable; but she had always seemed young for her years—and in any case she was only fifteen.

While Lady Frances scrutinized her charge Mary was looking anxiously at her governess.

“You are pale, Lady Frances,” she said. “Have you one of your headaches?”

Lady Frances put a hand to her brow and confessed that she had been feeling unwell for the last few days.

“You must go and lie down.”

Lady Frances shook her head. “And you must tell the Princess Anne of the appointment for tomorrow.”

“Oh, yes,” replied Mary, “I shall not forget.”

Face to face with William she thought that the stories she had heard about him might well be true. He looked as though he rarely smiled.

“Welcome to England, cousin,” she said; for the King and her father seemed to wish that she be the one to talk to him.

He inclined his head and she asked him how he liked England.

He liked it well enough, he answered.

What a dour creature he was. She would remember this conversation and report it all in her next letter to Frances. Better still keep it until they met. She smiled as she visualized that meeting.

“Very different, I’ll swear, from your Court at The Hague.”

“Two Courts could hardly be expected to be the same.”

She was thinking: But, Frances, it was so difficult to talk to him. He makes no attempt to carry on the conversation at all … and it simply dies out. I had to keep thinking of fresh subjects.

“Do you … dance much at The Hague?”

“Very little.”

“I love to dance. I love playacting too. Jemmy … the Duke of Monmouth, excels at it all … dancing, playacting …”

“Is that all he excels at?”

Flushing, suddenly remembering Jemmy with Henrietta Wentworth and Eleanor Needham, she did not answer the question but said, “Pray tell me about Holland.”

That forced him to talk and he did so briefly. It sounded a dull place to Mary; she was watching Anne, who was with their father, out of the corner of her eye, while she longed to be rescued from William who was so dull.

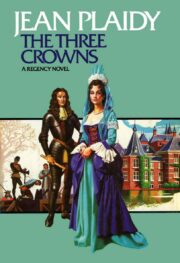

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.