He said slowly that he had heard one could not have too many friends.

“Then we will begin … without delay … being friends.”

This was his first meeting with his cousin Elizabeth Charlotte.

He found her entertaining, but he doubted whether she would make a good wife. She would wish to have everything done as she wanted it; and when he married he would want to be the master. That was one thing of which he was absolutely certain. It was all the more necessary because he was slight and delicate. He must show everybody that bodily weakness was more than made up for by mental ability and strength.

Elizabeth Charlotte was an amusing companion but she would not, he believed, make a good wife for a man such as he was.

She had an imperious habit of instructing him.

“Now, William,” she would say, “you must be more gallant. You must look pleased even when you do not win a game. You should really be pleased that I have won because after all if I am to be your wife, you will have to love me beyond all else … even beyond yourself—so you may as well start getting used to it.”

“And what of you? Will you not be obliged to love me better than anything else …”

But Elizabeth Charlotte had already dismissed that subject and was thinking of something else.

“I am to be presented to the Princess of Orange,” she said. “Aunt Sophia has warned me that I have to be very careful and remember to speak only when spoken to.”

“That,” said William, “will put a great tax on your memory.”

She agreed that it would.

“Well, I do not see why it should be such an ordeal. After all she is my own kinswoman. Perhaps she will be as pleased to see me as I’m supposed to be to see her. She is English they tell me.”

“I am too, because she is my mother.”

“But you are half Dutch, William. You are the Prince of Orange, which is why of course they want you to marry me.”

She was incorrigible and it was impossible to suppress her.

Sophia, who had herself been suppressed since her marriage to a minor prince, despaired of instilling the necessary good manners into the child.

“Elizabeth Charlotte,” she said severely, “I am depending on you not to disgrace me.”

Elizabeth Charlotte threw her arms about the aunt for whom she was sorry.

“I never will,” she declared.

“You must behave very discreetly when you pay your homage to the Princess of Orange. Remember that she is not only the Princess of Orange but the daughter of a King of England.”

“Oh, him,” said Elizabeth Charlotte. “They chopped off his head.”

“Hush, my child. Where do you learn such things?”

“Well, you see, Aunt Sophia, it’s history and you know how they are always telling me I must learn my history. Those are the things I can learn best.”

“Elizabeth Charlotte, you must try to be more serene. You should be more like William.”

“Like William! And not be able to breathe properly. And I don’t think, Aunt Sophia, that he stands up very straight. I shall be taller than he is, I am sure; and that is not a very good thing for a wife to be. Should I stoop? Should I wheeze to be a little more like William?”

“You are deliberately mischievous. I implore you not to be. You must be William’s good friend. If you are and come to love him while you are young, it will be so much easier when you are grown up. But who has told you you are to marry him?”

“Something in here …” She tapped her heart with a dramatic gesture. “Something in here tells me.”

“You imagine too much, my dear. And you have imagined this. You should be thinking of how you will conduct yourself before the Princess of Orange instead of dreaming of marriage plans which exist only in your imagination.”

“I am pleased. I do not think I want to marry William. I want to have a love match like yours. I think they are the best really.”

“Hush, child, hush. Go now to your room; your maids will prepare you. Remember all I have said.”

“I will remember, dear Aunt Sophia.”

From the Palace in the Wood to The Hague. Elizabeth Charlotte riding beside Aunt Sophia and her grandmother the Queen of Bohemia.

Elizabeth Charlotte sat upright. This was a very solemn occasion because of the presence of her grandmother—the Queen of Bohemia—who had once been so beautiful and was the sister of that poor King Charles I who had had his head chopped off.

Dreamily watching her, Elizabeth Charlotte was thinking of that King: and how the wicked Oliver Cromwell had not only killed him but driven his family out of their country. They were wandering about on the Continent, she had heard, being entertained by any Court that would have them. She imagined them as gypsies—barefooted, dark-skinned, singing a song or two and for their trouble being given the scraps that were left after the banquet.

“You must curtsy deeply to the Princess of Orange when you are presented,” Aunt Sophia was reminding her.

“Yes, dear Aunt.”

“And when the Queen of Bohemia leaves the Palace you must be ready to leave with her. Do not go off and hide with William, who will be there.”

“No, dear Aunt.”

Grandmother, Queen of Bohemia, nodded at her absently, and Elizabeth Charlotte imagined she was thinking of her poor brother having his head cut off.

When they arrived at the Palace she saw William and immediately called to him. The Queen of Bohemia and her daughter Sophia smiled at each other with gratification; it pleased them to see the friendship between the children.

“William wishes to show me the gardens,” said Elizabeth Charlotte. “May I go with him?”

When the children went off together William said: “But I did not wish to show you the gardens.”

“William,” chided Elizabeth Charlotte, “you will have to be sharper when you are my husband. I wanted to get away. Do you not see?”

“I see,” said William, a little sullenly, “that you wish everyone to dance to your tune.”

Elizabeth Charlotte pretended to play a pipe and called: “Dance, William, dance.”

He was annoyed and went into the palace; she followed him.

“Now,” she said, “we will play hide-and-seek. I shall hide and you shall seek.”

“You have come here to pay homage to the Princess of Orange. Have you forgotten?”

Elizabeth Charlotte clapped her fingers over her mouth.

“No. But they did give us permission …”

“Only to look at the gardens. Come along. I will take you to the reception chamber.”

Elizabeth Charlotte followed him. The reception chamber was an exciting place. The decorations were magnificent and there were so many people, and one woman with a very long nose who fascinated her. She tried not to stare but could not prevent herself.

That must be one of the longest noses in the world, she told herself. I wonder whose it is? I must know.

“Who is that woman?” she whispered to a man who was standing nearby. He did not seem to have heard for he took no notice.

Then she saw William, who had moved some little distance away from her.

“William,” she whispered. “Come here, William.”

William regarded her stonily and kept his distance.

“William,” she said a little louder. “I want to speak to you.”

This was not the manner in which to speak to the Prince of Orange. When they were alone he endured a good deal; but he would not in public.

“William,” she cried in a loud voice, “I want to ask you something.”

Still he ignored her.

“William,” she screamed, “who is that woman with the long nose?”

There was a hushed silence all about her. The long-nosed woman did not appear to have heard the interruption.

Elizabeth Charlotte felt her arm gently but firmly taken by a plump young woman and she was led out of the hall.

In the anteroom Elizabeth Charlotte tried to struggle free. “Who are you?” she demanded.

“Her Highness’s lady in waiting, Anne Hyde,” was the answer.

“Then how dare you lay hands on me? How dare you force me where I do not want to go?”

William had come into the apartment; as soon as he entered he smiled, which was strange for it was not a habit with him.

“William …” began Elizabeth Charlotte imperiously.

But William interrupted her. “You asked me a question in there. I’ll answer you now. Who is the long-nosed woman? You wanted to know. Well, she is my mother, the Princess of Orange.”

The Princess of Orange had sent for her son and as he stood before her she studied him intently. She wished that he could add a few inches to his stature. It would later be such a handicap for him if he remained small. She wished too that he could throw off that wheeziness of his, which really alarmed her. He must learn to stand up straight, for his stoop was growing more pronounced each week.

William guessed what she was thinking; it made him resentful—not against her, but against life which had given him the title of Prince and withheld all that was outwardly princely.

One day, he thought, I will show them that it is not necessary to be tall to be a king. Small men can be as brave—or braver—than big ones. He would show them … one day.

The Princess had no idea that her son read her thoughts; she said: “Pray be seated, William. I wish to speak to you about very important matters.”

He thought that she was going to reproach him for the behavior of Elizabeth Charlotte, not realizing that when events of such magnitude were happening in her family, the lack of decorum of a child was of small importance to his mother.

“Your uncle has returned to his kingdom.”

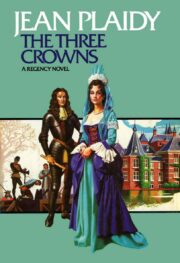

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.