Sarah was furious; but then Sarah often was furious. All the same she was aware of the power of the King’s favorite son; and although she might talk of upstart bastards out of his hearing, she was a little afraid of what he might do. Sarah knew that it was most essential for her to keep her place at Court if she were going to make the marriage that was necessary to establish her social position.

So before Eleanor came to Mary she had had an idea of what was happening and now that she was so knowledgeable of how people at Court conducted themselves, she was not surprised at the outcome.

“My lady,” said Eleanor, “I am with child and I must leave the Court very soon.”

“Is it Jemmy’s?” whispered Mary.

Eleanor nodded.

“Poor Eleanor. But what will you do?”

“Go right away from here and no one shall ever hear of me again.”

“But where will you go?”

“Do not ask me.”

“But Eleanor, can you look after yourself?”

“I shall be all right.”

“But I must help you.”

“My dear lady Mary, you are so kind and good. I knew you would be. That is why I had to say good-bye to you. But I shall know how to look after myself.”

“You should stay at Court. No one takes much account of these things here.”

“No, I shall go. But I wanted to say good-bye.”

Mary embraced her friend.

“Promise me that if you need help you will come to me?”

“My good sweet lady Mary, I promise.”

Mary told Anne what had happened, and how sorry she was for poor Eleanor.

“Sometimes,” said Mary, “I think I hate men. There is Jemmy who is as gay as ever while poor Eleanor is so unhappy she has to go right away. How different is my love for Aurelia.”

Anne nodded, and taking a sweet from the pocket of her gown, munched it thoughtfully.

Mary went into her closet and sitting at her table wrote that she was taking up her new crow quill to write to her dearest Aurelia.

She told her about the quarrel between that busybody Sarah Jennings and the Duke and Duchess of Monmouth, which was on account of Eleanor Needham. It was sad, wrote Mary, that a woman should be so ill-used. They had both been fond of Eleanor, and now she had left the Court to go, as she said, where no one would hear of her. How Mary longed to escape from the Court where such intrigues were commonplace.

“As for myself, I could live and be content with a cottage in the country and a cow, and a stiff petticoat and waistcoat in summer, and cloth in winter, a little garden where we could live on the fruit and herbs it yields.…”

Little Catherine died in convulsions ten months after her birth.

Mary Beatrice was heartbroken for a long time; Mary did her best to comfort her and for a while James deserted his mistresses and became the devoted husband.

There would be other children, he assured her; she was so young.

The little girl was buried in the vault of Mary Queen of Scots in Westminster Abbey; and after a short period of mourning Mary Beatrice was obliged to take her part in Court functions.

The devotion of her husband and the company of her two stepdaughters did a great deal for her over this unhappy time.

Although Mary mourned her half-sister, life had become too exciting for brooding on what was past. There was the gaiety of the Court, the friendships with the girls, none of which rivaled that with Frances, but Mary had much affection for friends such as Anne Trelawny. Her sister was very dear to her, and although at times she would feign exasperation because of Anne’s imitative ways and her refusal to change her mind once she had made it up, even when as in the case of the man in the park, she was confronted with the truth, the two sisters were inseparable.

Their stepmother was not in the least alarming. A little imperious, sometimes, a little pious often, but as she recovered from the death of her baby, ready to play a game of blindman’s buff, hide-and-seek, or “I love my love with an A.”

Then there was dancing, in which Mary was beginning to excel, and acting which was amusing. Sarah Jennings generally managed to infuse intrigue into the household which made it a lively one.

The years were slipping past and so absorbed was Mary by her own circle—and in particular Frances—that she forgot she was no longer a child: she had little interest in affairs outside her own domestic circle. A crisis occurred when there was a question of a husband being found for Frances.

A husband! But they had no need of men in their Eden.

“No one could ever love you as I do,” wrote Mary. “Marriage is not a happy state. How many faithful husbands are there at the Court, think you? They marry, tire of their wives in a month, and then they turn to others.”

It was alarming to contemplate. It reminded her of what she had seen when she surprised Jemmy and Henrietta Wentworth; it reminded her of the stories she had heard about her father and her uncle.

Unpleasant thoughts which it was best to avoid, but how could she avoid them when there was talk of Aurelia’s marrying!

For some months her anxiety persisted; and then the matter seemed to have been forgotten and the serene state of affairs continued: meetings with Frances on Sundays and holy days; and always those letters which must be smuggled out to the Apsley home. Her dancing master Mr. Gorley, the Gibsons, and very often Sarah Jennings and Anne Trelawny acted as go-betweens. It was a pleasant intrigue, for it must be carried on without the knowledge of Lady Frances Villiers who did not entirely approve of the correspondence.

So life went on merrily until Mary was nearly fifteen.

It was the day of the Lord Mayor’s feast and the King was dining at the Guildhall. This was one of the greatest occasions in the City of London and when Charles had told James that he thought Mary and Anne should be present James guessed that his daughters would soon be called upon to play their part in state affairs.

Anne’s favorite form of entertainment was attending banquets; as for Mary she enjoyed the pageantry. Both their uncle and father watched how the crowd cheered the girls; and how charmingly they responded. James was not surprised therefore when, on the day following the banquet, Charles sent for his brother, in order, said Charles, to discuss some small projects concerning the Lady Mary.

“James,” said Charles, “how old is Mary?”

“Fifteen.”

“Old enough, most would say.”

“For marriage, you mean?”

“What else? My dear brother, don’t look downcast. You must have realized that before long it would be necessary to find a husband for her.”

“She seems but a child to me.”

“Still, you would wish a brilliant parti for her?”

“I suppose it will be necessary.”

“Then the sooner the better.”

“She seems such a child.”

“It matters not what she seems but what she is. She is fifteen. Time she was betrothed. Have you a husband in mind for her?”

James hesitated. “There is Louis’s son,” he said at length. “I should like to see Mary Queen of France—and France is not so very far away.”

Charles grimaced, and James went on hotly: “Our own cousin, Charles. Why not?”

“Our little Mary is an important person. We must not forget that, as matters stand now, she could follow us to the throne. If you had a son, James, Mary’s marriage would not have been a matter of such deep concern.”

“Where could she make a better marriage than with France? The Queen of France. That is a position I should like to see her hold.”

“Alliance with a Catholic monarch, James?”

“With one of the greatest powers …”

“The people want a Protestant marriage, and I have thought of a likely husband for Mary.”

“And who is this?”

“Our nephew, William. William of Orange.”

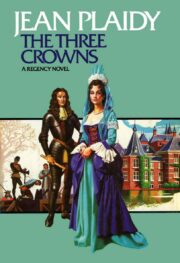

THE THREE CROWNS

Twenty-seven years before Charles decided to marry his nephew to his niece, William of Orange was born into a house of mourning. Eight days before his birth his father had died suddenly and his mother had ordered that her lying-in chamber should be hung with black crêpe; and even the cradle was black.

“A dismal welcome for a child,” mused the midwife, and she shook her head for she believed it to be an evil omen.

If the child were a boy, he would be the Prince of Orange; his father was lamentably dead, it was true; but she believed that the entry of a child into the world should be a matter for rejoicing.

The Princess of Orange was English. She was considered one of the most fortunate members of the unlucky Stuart family in those days of exile which had followed the execution of Charles I. She had helped her brothers, Charles and James, by giving them refuge in Holland; she had been devoted to them both and one of her most cherished hopes was to see Charles restored to the throne of England.

And now she had to face her own tragedy. The death of her William, Stadtholder of Holland, only a short time before she hoped to give him a son.

The child must be a son, she was thinking, as she lay in her darkened room. The child must be strong; he would be born ruler of his country. Never, it seemed to Mary of Orange, had a birth been so important; never would one take place in more tragic circumstances.

Mrs. Tanner, the midwife, bustled about the chamber giving orders. The Princess of Orange lay on her bed waiting.

In the anteroom Mrs. Tanner found several of the Princess’s women, and paused, for she could never resist a gossip.

“The mourning should be taken away,” she said. “It is not good. A little one coming into the world to black crêpe! What a welcome!”

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.