“Well, if you want to be rid of him, who better to take him from your bed than a mistress?”

“You are right, of course,” replied the young Duchess.

Night, and her attendants had left her. She was waiting for him, expectantly, angrily. It was five nights since he had been to her.

She did not believe she was pregnant. He had no reason to think so either. Yet he continued to spend his nights with his mistress.

It was humiliating. She, a Princess, to be left alone because he preferred another woman! She was his wife. He had pretended to be so pleased because she had crossed the seas to come to him; the Earl of Peterborough had wooed her urgently and tenaciously on his behalf in spite of her protests.

Now here she was—neglected on account of a mistress!

Was that his step outside the door? He was coming after all. She sat up in bed, clasped her arms about herself, apprehensive, terrified.

But it was not his step. She stared about her darkened room, and knew she was to be alone again.

She thought of him with that woman. What was the woman like? Beautiful she supposed. All mistresses were beautiful. Men went to them not for the sake of duty; it was all desire where a mistress was concerned. For the sake of such women, they left their wives … lonely.

Lonely. She was lonely!

She lay down and began to weep silently. Perhaps he would come and find her weeping. He would say: Do not be afraid. I’ll go away because that is what you wish.

He would be pleased to go because he preferred to be with his mistress than to do his duty with his wife. So it was duty?

Mary Beatrice’s eyes flashed angrily and she dealt her pillow a blow with a clenched fist.

Then suddenly she put her face on her pillow and gave way to her sobs.

A realization which bewildered her had come into her mind.

She wanted James.

THE PASSIONATE FRIENDSHIP

The girls made a pleasant picture walking in Richmond Park; four of them were arm in arm—the special friends: the Princesses Mary and Anne with Anne Trelawny and Sarah Jennings. Sarah was such good company and the Princess Anne kept screaming with laughter at her comments.

Behind were two of the Villiers sisters—Elizabeth and Katherine—outside the magic circle of friendship. Mary pressed Anne Trelawny’s arm to her side in a sudden gesture of happiness. It was pleasant to have such a friend; she felt completely at home with Anne Trelawny; and since she had always been devoted to her sister, she was now in the company she loved best. Sarah Jennings was a little overbearing, but Anne thought her so wonderful that Mary accepted her as a member of the quartette.

Princess Anne peered shortsightedly ahead and said: “Let’s go toward that tree over there.”

Following the direction in which she was pointing, Mary could see no tree; but there was a man standing on the grass.

“It’s not a tree, Anne,” said Mary. “It’s a man.”

“Oh no, sister, it’s a tree.”

“It’s a man,” insisted Mary.

Anne turned away and replied: “I’m sure it is a tree.”

“Well, we’ll go and see. I am determined to show you that you are wrong.”

Anne shrugged her shoulders in her lazy way. “Oh, I’m sure it’s a tree. I don’t want to go that way now. Let us go back to the Palace.”

Mary looked reproachfully at her sister. Anne must be taught a lesson, and Mary was going to teach her that she must not make observations and insist that they were true before proving them.

Releasing Anne Trelawny’s arm and taking her sister’s she led her across the grass. As they came near to the object of dispute, it began to walk.

“There,” cried Mary triumphantly. “You cannot doubt now what it is?”

Anne had turned her head and was smiling blandly in the opposite direction. “No, sister,” she said, “I still think it is a tree.”

Exasperated, Mary said: “Oh, Anne, there is no reasoning with you. Let us go back to the Palace.”

As they came within sight of the Palace she forgot to worry about this unfortunate aspect of her sister’s character because she saw the Duke of Monmouth giving his horse to one of the grooms.

A call from Jemmy was always a pleasure.

Monmouth had called on the sisters whom he knew were always pleased to see him. He had thought of a new idea for bringing himself to his father’s notice; not that that was necessary for Charles was always very much aware of him; but Monmouth longed to show how he excelled in all courtly attainments, how much more popular he was than his Uncle James, how much more the people esteemed him than they did his uncle. When Monmouth had first heard that James was to have a young wife he had been angry and depressed. A young wife would probably mean sons, and once a son was born to James, Monmouth’s hopes of being legitimized would completely disappear. It was only while there would be no one to follow James but his two daughters that there was a chance that Parliament would agree to make a male heir by this legitimization; and once the Parliament wished that, Charles, Monmouth was sure, would be very ready—or at least could be easily persuaded—to agree.

Unfortunately James was now married—and to a young and beautiful girl. It was almost certain that there would be issue. Then the bell would toll, signifying the burial of Monmouth’s hopes.

But Jemmy was by nature optimistic and exuberant. He never accepted defeat for long. The marriage was one of the biggest blows to his hopes that could have been given him; and yet almost immediately he began to see a glint of brightness.

The celebrations of the last Fifth of November had been an inspiration to him. Whenever he heard the shout of “No popery” in the streets he rejoiced. James might produce legitimate sons but he was a Catholic and the people showed clearly on every possible occasion that they did not want a Catholic on the throne.

The young Duke of Monmouth had, in the last weeks, become a man deeply interested in matters of religion. He was seen at his devotions frequently; although he continued to live as gaily as anyone at the Court, his conversation was spattered with theological observations. He was ostentatiously Protestant; and already the Protestants were beginning to look on him with great favor.

The seed was being sown. It might not bring forth a good harvest but that was a chance he had to take. Against the Catholic Duke of York, the legitimate successor to the throne of England, there was the Protestant Duke of Monmouth—a bastard it was true, but a little stroke of the pen could alter that.

Perhaps, then, he mused as he made his way to Richmond Palace to ingratiate himself with the Duke’s young daughters, the marriage was not altogether a bad thing. If the young Duchess failed to produce the heir—and he prayed that she would fail to do this—if it were a plain contest between York and Monmouth … well, who could say what the outcome would be? But he must hope there would be no offspring; these young children had a way of worming themselves into the hearts of the people, were they Catholic or Protestant.

He had heard talk too that Charles was thinking of taking the education of Mary and Anne out of their father’s hands since the Catholic marriage. All to the good. Let the people understand that the King was aware of the dangerous influence of Catholicism which had tainted the York branch of the family. It would help them to think more kindly of Protestant Jemmy.

“Hail, cousins,” cried Monmouth, as the sisters hurried to him to be embraced.

“Great news. Can you dance? Can you sing?”

Anne smiled and nodded but Mary replied: “We are not very good, I am afraid, cousin Jemmy.”

“Well, we will soon remedy that. Now listen. I am arranging for a ballet to be performed before His Majesty. How would you like to play parts in it?”

Anne said: “It will be wonderful, Jemmy.”

“But we are not clever enough to perform before His Majesty,” added Mary.

“My father is lenient toward those he loves.” Jemmy, Mary noticed, always referred to the King as “my father,” as though he were afraid people were going to forget the relationship.

“But he does not care to be wearied,” put in Mary sagely. “And I fear that we might do that.”

Monmouth put his head on one side and studied the girls shrewdly. Mary was wise for her age; and there was truth in what she said.

“Suppose,” he suggested, “you danced and recited for me now. Then I could judge whether you were good enough to perform before my father.”

Anne was willing enough. It never occurred to her to worry what people thought of her. If they did not like what she did, she would shrug her shoulders and forget. Mary was different; she hated not to be able to please.

Anne performed carelessly and badly; Mary made too much effort and was equally bad.

“I have an idea,” said Monmouth, “you shall have lessons. Then I think you will be very proficient. I’ve set my heart on your dancing with me before the King. In fact, this has been written with parts for you in mind. So it has to be.”

“Shall we need many lessons, Jemmy?” asked Mary.

“Very many and with the best teachers. Leave this to me.”

It was wonderful, Mary told Anne afterward, to be part of Jemmy’s ballet. Jemmy said that they would be at Court and that it was time they were there.

“I’ve always wanted to go to Court,” Anne answered. “Sarah says we should be there. Sarah would enjoy it … and of course if we were there so would she be.”

“We must do our best to improve our dancing,” said Mary.

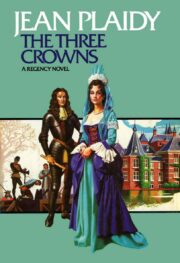

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.