When the party arrived at Whitehall the bride was conducted into the palace and there the King presented her to his Queen.

Mary Beatrice was greeted by the quiet Catherine with affection, while the King and the Duke looked on benignly. Mary Beatrice’s mother had told her that the Queen of England would be her friend because, like herself, she was a Catholic living in a country where the recognized religion was that of the Reformed Church.

“We will have much in common,” Catherine told her; the Queen’s voice was a little sad, for she was wondering how this young and clearly spirited girl would deal with her husband’s infidelities. She, Catherine, had been bewildered, humiliated, and deeply wounded by those of the King. She hoped that Mary Beatrice would not have to suffer as intensely as she had. “I trust,” went on Catherine, “that we shall be friends and that we shall have informal hours together.”

Mary Beatrice thanked her and then turned her attention to the two young girls who were being brought forward.

These were her stepdaughters—the Princess Mary and the Princess Anne. She studied them eagerly for the elder was not so many years younger than herself. Mary was about eleven years old—tall, graceful, with long dark eyes and dark hair. Her manner was serious and because Mary Beatrice guessed she was as apprehensive as she was herself, she felt a longing to show her friendship for this girl, and for the second time her spirits were lifted and the prospect of her new life seemed a little less grim.

It was possible to have a little informal conversation with her stepdaughters and then she realized that neither of them resented her and were anxious to be friendly.

“My father tells me that you will be as a sister to us … just at first,” Mary told her. “But you are in truth our new mother.”

“I will do my best to be all that you wish of me,” answered Mary Beatrice.

She looked at Anne who gave her her placid smile; and she knew at once that they would help her to bear her new life.

Charles smiled knowledgeably at his brother.

“I trust you are taking advantage of your new state, brother?” he asked lightly.

James frowned. “She is beautiful, but very young.”

“It is rare that men complain of the youth of their mistresses or wives.”

“She is but a child and they have brought her up with a craving to be a vestal virgin.”

“I trust for the honor of our house she can no longer aspire to such folly.”

James was moodily silent and the King went on: “Some of your enemies are suggesting that, having made this Catholic marriage, you should for the sake of peace retire from Court. It was hinted to me only the other day. How would you like, James, to leave Court and take your little beauty into the country?”

“My place is at Court.”

“So think I,” said Charles. “But methinks also, brother, that if you were as successful at courting your wife as you are at courting trouble you would by now have persuaded her that the life of a vestal virgin is not nearly so exciting as that of Duchess of York.”

“I do not propose to leave Court.”

“Nor do I propose that you should. I have already said so. But the people are not pleased with you, James. You stand for popery and the people in these islands do not like it.”

“What am I to do?”

Charles lifted his shoulders. He too secretly stood for the Catholic Faith; he had even made a bargain with Louis to bring his country back to Catholicism—yet he dealt with these matters shrewdly, graciously, and secretly. Why could not James do the same?

“Act with caution, brother. Stand firm. Remain at Court. Honor your little bride. Let every man know that you realize he envies you the possession of such an exquisite young creature, which I am sure he does. Do your duty. Let the Court and the people know that while she be young and so beautiful and a Catholic she is also fertile. Do this, James, and do it boldly. And, would you like a further word of advice? Then get rid of the mother.”

“But my wife’s great consolation is her mother.”

Charles smiled shrewdly. “It is a fact, brother, that when a Princess comes to a strange land and is a little … recalcitrant, she changes when she is no longer surrounded by relations. The old lady reminds her daughter by her very presence of all that she has missed in her dreary convent. Get rid of the mother, and you will find the daughter becoming more and more reconciled to our merry ways. There is little room for vestal virgins and their dragons here at Whitehall.”

James was silent. Charles who had charmed Mary Beatrice, who conducted his affairs with skill, who was a Catholic at heart and kept the matter secret for the sake of expediency, who had dared make a treaty with France which could have cost him his throne, whose wife was as Catholic and as foreign to Whitehall as Mary Beatrice and yet was in love with him—must understand what was the best way to act.

It was six weeks since Mary Beatrice had arrived in England. Christmas was over and she was astonished at the extravagance with which it had been celebrated. She had discovered that her charming brother-in-law scarcely ever spent his nights with the Queen; that fidelity and chastity in this island were qualities which, among the King’s circle, were regarded with incredulous pity; she was surprised that Queen Catherine longed for her husband’s company almost as intensely as Mary Beatrice prayed she would not have to endure hers; this Court was gay and careless; it was immoral and irreligious. It was all that she had feared it would be and yet she was a little fascinated, if not by it, by certain personalities. The chief of these of course was the King. He was making her fascinated by his Court as she was a little by himself.

When, during the Christmas festivities, she heard her mother was to leave England, she wept bitterly.

Duchess Laura comforted her, pointing out that she could not leave Modena and her son, the young Duke, forever. She had done an unprecedented thing when she had come to England with her young daughter, but now Mary Beatrice was old enough to be left.

“I shall die of sorrow,” declared Mary Beatrice.

“You will do no such thing. You have your friends, and your husband is kind to you.”

Mary Beatrice shivered. Kind he was; but she wished there were no nights. If it were always daytime she could have endured him.

“When you leave me,” she told her mother, “my heart will be completely broken.”

“Extravagant talk,” said the Duchess, but she was worried.

When by the end of December the Duchess had left for Modena, James discovered his wife to be in such a state of melancholy that he wondered whether he should leave her to her Italian women attendants for a few days. It was disconcerting to know that he was almost as great a cause of her wretchedness as her mother’s departure.

A few nights after the Duchess had left, Mary Beatrice said to her husband: “When I am with child as I must soon be, then you need not share my bed.”

James looked at her sadly.

“Then,” he said slowly, “it shall be as you wish.”

Her ladies had prepared her for bed. She shivered as she did every night. Soon he would be there. She anticipated it with horror: his arrival, the departure of the attendants, the dousing of the candles.

He was late. They were chattering away, not noticing, but she did. She must be thankful, she told herself, if the dreaded moments were delayed even for a short while.

They talked on and on—and still he did not come.

“His Grace is late,” said Anna.

“Perhaps we should leave you,” suggested one of the others.

Mary Beatrice nodded. “Yes, leave me. He will be here soon.”

So they left her and she lay shivering in the darkness waiting for the sounds of his arrival.

They did not come.

For an hour she lay, expectant; and finally she slept. When she awakened in the morning, she knew that he had not shared her bed all night.

She sat up, stretched her arms above her head, smiled and hugged herself.

If all nights were as the last one would she enjoy living at her brother-in-law’s Court? The gowns one wore were exciting; so was the dancing; she did not greatly care for the card playing but she need not indulge in that too much. She was one of the most important ladies of the Court and the King made sure that everyone realized this.

How strange this was! Her mother had left her; she was alone in a foreign land; yet, when she was free of the need to do her duty as a wife, she was less unhappy than she had believed possible.

The next night she waited and he did not come; and during the following day she knew why.

It was Anna who told her, Anna who loved her so much that she shared her unhappiness to a great degree and knew her mistress’s mind as few others did.

“He spends his nights with his mistress. I do not think you will often be worried by him. This woman was his mistress before the marriage and I have heard that he is devoted to her.”

“His mistress!” cried Mary Beatrice. “But he has a wife now.”

“But the marriage was for state reasons. He will continue with his mistresses. He is like his brother.”

“I see,” said Mary Beatrice blankly.

“I do not think you will be greatly troubled with him in future.”

“I shall tell him that it does not please me that he should continue with this woman.”

Anna opened her eyes wide. “But do you not see? While he is with her, you are free of him.”

“Yes, yes,” said Mary Beatrice. “That is a matter for which I must be grateful.”

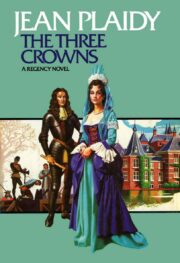

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.