Her hand was in his; he held it firmly as though to say she should never escape him. She was shivering, believing that this consummation of which she knew so little but which she dreaded, would be even more alarming, even more shocking than she had feared.

He whispered to her: “You are happy to be here?”

She was too young to hide her feelings. “No, no,” she answered.

He was taken aback, but the desire in his eyes was touched by a certain tenderness. “You are so young. There will be nothing to fear. I will do everything in my power to make you happy.”

“Then perhaps you will send me home.”

Those about them had heard her words. Her mother was frowning, and Mary Beatrice knew she would be scolded but she did not care. She had always been brought up to believe it was wrong to lie. Well, she would tell the truth now.

James smiled whimsically as he broke the horrified silence. “My little bride,” he said kindly, “it is natural that you should be homesick … just at first. Soon you will understand that this is your home.”

The next day the marriage was solemnized in accordance with the rites of the Church of England and Mary Beatrice then wore, as well as the diamond ring which had been put on her finger at the proxy marriage, a gold ring adorned with a single ruby which James gave her during this ceremony.

James had done all he could to pacify her; he sat beside her at the banquet which followed; he expressed concern at her poor appetite; he coaxed her and endeavored to persuade her that she had nothing to fear from him. She wept bitterly and made him understand that no matter how kind and considerate he was, he had torn her away from the life she had chosen and now she would be forced to live in a manner repugnant to her.

James was a practised lover, his experiences in that field being vast, and he used all his powers to lessen the ordeal which he understood faced this young wife of his.

He explained to her the need for them to have sons; their son, he told her, might well be King of England; it was for this reason that marriages were arranged. He was sure she would wish to do her duty.

Mary Beatrice lay shuddering in the marriage bed. She prayed, while she thought he slept, that something would happen to prevent the events of that night ever being repeated. She did not know that James lay wakeful beside her, thinking of the passion he had shared with Anne Hyde before their marriage, asking himself what happiness there was going to be for him and this girl who was nothing but a child, nearer to his daughters than to him.

The bride must surely be one of the most beautiful girls in the world. Anne Hyde was far from that. Yet what a travesty of his first marriage was this. He believed that she dreaded his touch, loathed him for the loss of her virginity; she had made him feel ashamed, a raper of the innocent.

This was not the union for which he had longed.

The wedding party did not stay long in Dover, but were soon on their way to London. All along the route people came from their houses to see the Italian bride. She was viewed with curiosity, admiration, and suspicion. She was after all a Catholic and the Duke was suspected of being one; and although her youth and beauty enchanted all who beheld her, there were murmurs of “No popery.”

The Duke rode beside his bride and in spite of his misgivings he could not disguise his pride in her, and as he watched her acknowledging the acclaim of the people with grace and dignity in such contrast to the frankness in which she had shown her dislike of him, his spirits lifted a little. She was after all a Princess, and would know what was expected of her.

He began to think with pleasure of his latest mistress. How differently she would welcome him! A man could not make continual love to a woman who was repelled by the act. But Mary Beatrice would change—and when it had ceased to become a matter of duty, when she could respond with ardor, then would be the time to build up that idealistic relationship for which he, being a sentimental man, longed.

They slept at Canterbury the first night where the citizens welcomed them with affection. Pageantry was always a delight in Restoration England; the people had been too starved of it during puritan rule, not to find pleasure in it, whatever the cause; but Mary Beatrice could find none in the beauty of the Cathedral City; she felt bruised and bewildered and there was nothing for her but the thought of past horror and the dread of more to come. And the second night in Rochester her mood had not changed.

And so they came to London and at Gravesend, amid the applause of the spectators, the Duke of York took his Duchess aboard his barge, which, decorated with evergreen leaves, was waiting for him.

James had successfully hidden his disappointment in his marriage and appeared to be quite delighted with his bride. As they stepped aboard, to the accompaniment of sweet music which was being played by the barge musicians, he told her that somewhere on the river they would meet the royal barge and he was sure that his brother would be on board.

“The King will wish to greet you in person at the earliest moment,” he told her, and when he saw the look of fear cross her face, he smiled grimly. The reputation of Charles had in all likelihood reached her, as his own no doubt had, and she was going to be as repulsed by the King as by the Duke. He hoped she would not be as frank with Charles as she had with him; but he ruefully accepted the fact that Charles would doubtless know how to deal gracefully with the situation whatever it should be.

“You will have nothing to fear from the King,” he told her. “He has a reputation for kindness and he will be kind to you.”

Her expression was stony; he thought ruefully she would be almost unbelievably beautiful if she would smile and be happy.

Down the river sailed the barge; the bells were ringing, and sounds of revelry came from the banks; there were cheers, and shouts for the bride and groom to show themselves. This they did, waving to the people as they sailed along. James was once more pleased to notice that his wife did her duty in this respect. How different it might have been, sailing down the river on this November day, if he had had a happy young girl beside him who was prepared to love him as he was her.

At length they met the royal barge, and a messenger boarded the Duke’s with a command from the King. His Majesty was eager to greet his brother’s bride and he wished the Duke to bring her to him without delay.

James smilingly reassured her, saw the fear in her face, and thought it was a pity she, being so young, was unable to hide her feelings. He was dreading that moment when she came face to face with her brother-in-law—the rake of rakes, the man whose reputation was known throughout the whole of Europe—Charles, King of England, whose mistresses ruled him and the only comfort in that situation was that they were so numerous.

Poor little Mary Beatrice! They should never have made such a little nun of her.

Charles was waiting on deck, and taking his wife’s hand James led her forward. He saw the lovely eyes lifted to that dark humorous face, already marked with debauchery yet losing none of the charm which had been there when Charles was a young man of twenty. Perhaps there was a deeper kindliness in the lazy, yet shrewd eyes, perhaps the charm increased with the years which was nature’s special concession to one who loved life—as he loved his mistresses—passionately while he refused to take it seriously.

Mary Beatrice bowed low but Charles took one look at her lovely face, her graceful body, and with an exclamation of delight lifted her in his arms.

No one could dispense with ceremony more naturally and gracefully than Charles and whatever he did, he had the gift of making the action seem acceptable and charming.

“So I have a sister!” he cried. “And what a delightful one! I trust my subjects have been giving a good account of themselves.” He glanced quickly at James and his eyes said: You fortunate devil! Would I were in your place.

Mary Beatrice was surprised at the complete revolution of her feelings. She had come on board prepared to hate this man; she had been fighting her feeling that she might not betray the aversion she felt for him. Instead, she was smiling, glad to put her hand in his, finding it a pleasure to be led to the rail to be seen standing side by side with him by the watchers on the bank.

“Why, my dear,” he said in that soft tender voice he invariably used for attractive women, “you are very young, and you have come a long way from home. It is a trying ordeal, I understand full well, for I remember when I was young I was forced to leave my home … under very different circumstances than those in which you have left yours. The homesickness … the yearning … my dear sister, they have to be lived through to be understood. But remember this, that although you suffer from leaving your home, you bring great pleasure to us because you have come to live among us. Now you shall sit beside me and tell me what you have left. I have a fondness for your mother, of which I shall tell her soon. I remember how desolate she was when you lost your father and how she brought up you two children. A bit stern eh? Soupe maigre? Ah, I have heard of that! Rest assured, little sister, we shall not force you to eat soupe maigre while you are with us.”

Mary Beatrice was smiling, and James looked on in astonishment. What power was this in his brother to charm? How could he, in his careless way, in a few short moments put at ease this girl whom he himself had tried so hard to please.

He could not answer that question. All he knew was that from the moment Mary Beatrice met the King she became a little less unhappy, a little more reconciled to her marriage.

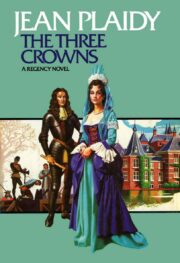

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.