When Susanna understood that if James married her against the wishes of the King and the country he might be rejected by them, she herself decided to break off their friendship.

There was one last interview between them before James went off to join the Navy, for war with the Dutch had broken out again.

“I see,” said Susanna, “that I can never be happy again. For if I married you I should continually reproach myself for the harm I had done you; and since I cannot, I shall think of you with longing all my life.”

“Do not despair,” cried James. “Once I have beaten the Dutch I will fight for our happiness.”

She smiled sadly, for she knew that he would not.

She begged though to be allowed to keep his promise of marriage. It would be a little souvenir of the esteem in which he had held her and show the world that theirs had been an honorable relationship.

He declared he would come back to her. They embraced affectionately. Then James went off to win the battle of Solebay and restore to the Navy some of its lost prestige.

Meanwhile in London plans went ahead to marry the King’s brother with as little delay as possible.

James, Duke of York, being the only living brother of the King and heir presumptive to the British throne, was one of the most desirable matches in Europe, but the negotiations for his marriage to a suitable lady were again and again frustrated.

The first choice—favored by the French—was Madame de Guise, but James would not have her, complaining that she was short, ungainly, and did not enjoy good health so would be unlikely to bear him children. The second, Mademoiselle de Rais, he also declined for similar reasons. The Archduchess of Inspruck seemed an ideal choice as far as he was concerned, for she was a Catholic; and he sent off Henry Mordaunt, Earl of Peterborough, who was not only a servant but a friend, to make the necessary arrangements with all speed. Unhappily before the marriage could be completed the mother of the Archduchess died and she decided to choose her own husband. She chose the Emperor Leopold I.

There were three other ladies who were considered suitable: these were the Princess Mary Anne of Wirtemburg, the Princess of Newburgh, and Mary Beatrice, Princess of Modena. These three were charming girls, but the most delightful of all was Mary Beatrice who was only fourteen years old.

Peterborough first visited the Duke of Newburgh with the object of reporting to his master on his daughter. He found her charming, but a little fat—and since she was so now, he asked himself what she would be in ten or fifteen years’ time. He did not believe her worthy of his master, and as his object was known and he went away without completing arrangements for a marriage, this was never forgiven the Duke of York but remembered against him by the young lady for the rest of her life.

A picture Peterborough acquired of Mary Beatrice enchanted him for it showed him a young girl of dark and startling beauty, but since she was not yet fifteen it had been decided that negotiations should go ahead for bringing the Princess of Wirtemburg to London.

Mary Anne of Wirtemburg was living in a convent in Paris and hither Peterborough hastened, where he asked for an interview with the Princess and told her that her hand was being sought by James, Duke of York, heir presumptive to the British crown. Mary Anne, a gay young girl who found convent life irksome, was delighted, and being inexperienced unable to hide this fact. Peterborough was relieved, although he thought often of that lovely young girl who was by far the most beautiful of all the candidates.

These negotiations however were destined to fail, for suddenly Peterborough had an urgent message to stop them.

Having already informed Mary Anne that she was to marry the Duke, he was horrified by these instructions. It appeared that the King’s mistress, Louise de Kéroualle, who was now the Duchess of Portsmouth, had selected a candidate—the daughter of the Duc d’Elbœuf; and although the King guessed that his mistress’s plan was to bring her fellow-countrywoman into a position of influence that they might work together, so besotted was he that he allowed the negotiations already begun by Peterborough to be withdrawn.

It was typical of Charles that while he listened to his mistress and made promises to give her what she asked, he should find an adequate excuse for not doing so.

Mademoiselle d’Elbœuf he decided was too young for marriage to the Duke of York, being not yet thirteen; and James, being of more sober years, needed a woman who could be a wife to him without delay. So Louise de Kéroualle did not have her way as she had hoped; but at the same time it was impossible to reopen negotiations with Mary Anne of Wirtemburg.

The Duke of York must be married. There was one candidate left. It was therefore decided that plans to marry James to Mary Beatrice of Modena should go forward without delay.

When James saw the picture of Mary Beatrice he was completely captivated and felt faintly relieved—although he would not admit this—that Susanna had rejected him.

When he showed it to Charles the King agreed that there was indeed a little beauty.

“She reminds me of Hortense Mancini,” said Charles, nostalgically, “one of the most beautiful women I ever saw. You’re in luck, brother.”

James believed that he was. “Why,” he said, “she cannot be much older than my daughter Mary.”

“I can see you are all eagerness to have her in your bed.”

James sighed: “I have a desire for domestic happiness. I want to see her at my fireside. I want her and Mary and Anne to be good friends.”

Charles raised his eyebrows. “Spoken like a good bridegroom,” he said. “One thing has occurred to me. The Parliament will do all in its power to stop this marriage. Your little lady is a Catholic and they will not care for that.”

“We must make sure that the matter is settled before Parliament meets,” said James.

“I had thought of that,” Charles told him slyly.

He wanted to ask: And how is Susanna at this time? But he did not. He was kind at heart; and he was relieved that James had come out of that madness so easily.

Henry Mordaunt, Earl of Peterborough, Groom of the Stole to the Duke of York, had a task to his liking. He was going to Italy to bring home Mary Beatrice Anne Margaret Isobel, Princess of Modena, and although his previous missions of this nature had ended in failure, he was determined this should not; he was secretly delighted because as soon as he had seen the portrait of this Princess he had made up his mind that she was the ideal choice for his master.

Peterborough was devoted to the Duke of York; he was one of the few who preferred him to his brother; and since Mary of Modena was quite the loveliest girl—if her picture did not lie—that he had ever seen, he wanted to bring her to England as the new Duchess of York.

James had pointed out to him the necessity for haste. “Because,” James had declared, “unless the marriage has been performed before the next session of Parliament, depend upon it they will make an issue of the fact that she is a Catholic and forbid it to take place.”

Peterborough had therefore left England in secrecy; he was, he let it be thought, a private gentleman traveling abroad for his own business.

When he reached Lyons after several days, and rested there for a night before proceeding, he was received with the attention bestowed on wealthy English travelers, but without that special interest and extra care which a messenger from the Duke of York to the Court of Modena would have received. He planned to be off early next morning that very soon he might be in Italy.

While he was resting in his room a servant came to tell him that a messenger was below and would speak with him. Peterborough asked that the man be brought to his room, thinking that a dispatch had followed him from England. To his surprise it was an Italian who entered.

“I come, my lord,” he said, “with a letter from Modena.”

Peterborough was aghast. How did the writer of the letter know he was on his way to the Court. Who had betrayed his mission?

He took the letter and the messenger retired while he read it, but the words seemed meaningless until he had done so several times.

“The Duchess of Modena has heard of your intention to come here to negotiate a marriage for her daughter Mary Beatrice Anne Margaret Isobel, and wishes to warn you that her daughter has no inclination toward marriage, and that she has resolved to enter a convent and lead a religious life. I thought I must give you this warning, that you may convey to your Master His Majesty King Charles the Second and His Royal Highness the Duke of York, that while the house of Esté is very much aware of the honor done it, this marriage could never be.” This was signed “Nardi,” Secretary of State to the Duchess of Modena.

Peterborough was bewildered. His secret mission known! And moreover the Duchess already declining the hand of the Duke of York for her daughter!

And these messengers, what did they know of the contents of the letters? Was the project being discussed in Modena and throughout the countryside? Was this going to be yet another plan that failed?

Peterborough was determined that this should not be.

He asked that the messenger be sent to him and found that there were three of them. He offered them refreshment in his room.

While they drank together, he said: “It is strange that the Duchess of Modena should think it necessary to write to me. I am only a traveler who is curious to see Italy.”

But of course they did not believe him; and as soon as they had left him he sat down to write to Charles and James, to tell them of this incident.

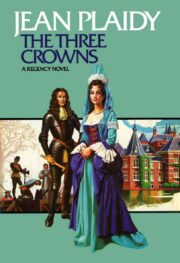

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.