“We must be careful,” he said. “This must be a secret between us. You will have to be cautious when you are with the priest. The people would be against us if they knew.”

“You in particular, James. For myself I do not believe I am long for this world. I have not told you before, but I think you should know now. I have a recurring pain in my breast and I know it is serious.”

He was horrified. “But the doctors …”

“They can do nothing. I know something of what this means. I did not want to tell you, but now you will understand my urgent desire to prepare myself. And I do not want to leave you, James, knowing that I did not share with you all that I have come to understand.”

They wept together, he deeply regretful of all the anxiety he had caused her, she sorry for her nagging sarcasm.

“We have been like two children lost in a wood,” she said. “But now we see a light.”

He demanded to know more of her illness and would not accept her pessimistic view.

He cares for me in very truth, she thought; and somehow the knowledge made her the more sorrowful.

“The light is the Holy Catholic Faith, James. Do not ignore it,” she entreated.

He told her that he loved her; that he had never regretted the decision he had made when all his family were against him. They would be together now … for the time that was left to them.

“Together in mind and body, James?” she asked.

“In all things,” he answered.

The Duchess and Duke came frequently to Richmond. They wanted, they said, to be together with their children.

Mary was horrified to find that her feelings had changed toward them. She could no longer relax happily in her father’s arms. When he took her on to his knee she could not help thinking of Margaret Denham who had died because of him. It was complicated and difficult to understand, but it was repellent. Her mother had changed. She had become grotesquely fat; her face was the color of uncooked pastry; and with her bloodshot eyes she was not an attractive sight. Mary could not help comparing her with some of the beautiful women she saw frequently.

Sometimes her father would declare that they were all going to be happy together. He would tell her, Anne and poor little Edgar, who was growing more weak every day, stories of his past; but somehow they no longer fascinated as they once had. Mary was beset by doubts that they were only true in part; that if one could look into them with the farsighted eyes of an adult one would discover something unpleasant.

One day the Duchess sent for Mary, and when she went to her apartments the little girl found her mother lying on her bed. Her face was sallow and the sight of her propped up on pillows with her hair falling loose about her shoulders made Mary want to glance away.

She took Mary’s hand and bade her sit on the bed so that they could be close.

“You are the eldest of the family,” she said. “Always remember that.”

“Yes, mother.”

“There is one thing I want you always to do for me. Look after Anne.”

“But …”

“I know you are thinking that you are only a little girl and that you have your father and me, but I am thinking of the future when we may not be here.”

Mary’s face puckered. “You are going away?”

“No, my dearest child, not now. I am thinking of the time ahead when perhaps it will be necessary for you to be a mother to your little sister and brother. You will, won’t you?”

“Yes, mother.”

“Come and kiss me. It will seal our bargain.”

Mary hid her repulsion and solemnly kissed her mother.

Elizabeth Villiers saw Mary leaving her mother’s apartment. She looked at her slyly as though to suggest that she knew what had taken place. How could she? Mary asked herself. But she was beginning to believe that Elizabeth Villiers knew a great deal.

When they were alone together Elizabeth whispered: “Are you going to be one?”

Mary did not understand.

“It won’t be allowed,” Elizabeth went on virtuously. “We won’t let you … even if you want to.”

“I don’t understand you?”

Elizabeth put her lips close to Mary’s ear. “Your mother’s one. They are all saying so. They’re wicked. They all go to hell. That’s where your mother’s going.”

Mary was horrified. Had her mother not suggested that she was going away?

“Yes,” said Elizabeth, “they frizzle like a sheep on the spit. The good angels turn them round to make sure they get thoroughly brown on all sides. That’s what happens in hell and they all go there.”

“You’re … hateful.”

“Because I tell you the truth?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Don’t you know anything?”

“Yes,” said Mary, “I know I hate you.”

“You mustn’t hate. You go to hell for hating.” Elizabeth made the movement of turning a sheep on a spit and there was an ecstatic light in her eyes.

“Stop it,” said Mary.

“That doesn’t stop. It goes on for eternity, and you know that means forever and ever … amen.”

Mary turned to go but Elizabeth caught her arm. “We won’t have Catholics here,” she said. “Your mother’s one. She tries to hide it but everybody … except you … knows it.”

Mary wrenched her arm free of her tormentor, and as she ran from her, heard Elizabeth’s taunting laughter.

She was puzzled and uneasy.

The King had heard the rumors of his sister-in-law’s conversion and guessed that James was following her lead; he himself favored the Catholic faith and would have proclaimed this fact but for the memory of those early wanderings of his. He was more realistic than James and understood the temper of the people better than his brother. James was a sentimentalist; Charles was never that.

Charles hated intolerance and he would have liked to bring some relief to his Catholic subjects. It would give him a great deal of pleasure to reunite England with Rome—providing of course the changeover would not bring about trouble, which was the last thing he wanted. But he was a King and a Stuart and in spite of his good nature and love of peace there was in him an innate belief in the Divine Right of Kings. Why be a King if one must be governed by a Parliament? How tedious constantly to be told that he could not have this or that grant of money! And he was a man who always had a demanding mistress at his elbow.

Every Stuart would be haunted throughout his life by the martyred King Charles I. They would always remember how, being in conflict with his Parliament, he had lost his head. No Stuart should ever run afoul of his Parliament, and yet how could he but help it?

The nation was behind him, and he was convinced that the people would never allow the head of the second Charles to roll, for his father—with all his nobility and virtuous ways—had never appealed to his subjects as his merry son had done.

Could he take a chance?

How many chances had he taken during the days of exile—and after? It was second nature to take chances.

He needed money—desperately; and the Parliament would not grant it to him, so his eyes were on France. His sister—his beloved Minette, the favorite of all his sisters, who was married to the brother of Louis XIV—had been in secret correspondence with him. Minette had assured him of Louis’s good will toward him; she had made him see that a French alliance was imperative. Imperative to the King or to the country?

“The King is the country,” said Charles to himself with a cynical smile.

Sir William Temple had formed an alliance with Sweden; but negotiations were going on with Spain at the same time—and of course France.

Colbert de Croissy, the French ambassador, had proposals to put before him; he brought letters from Minette; Louis was ready to pay the King of England handsomely for his cooperation, but it was an alliance which, for the time being, must be kept secret even from the King’s ministers.

What Louis wanted was alliance with England, and he would feel happier if this alliance were with a Catholic England. The King of England was half French; his mother had been a Catholic and it was natural that he should lean toward her religion. The King would be willing enough; but England was a Protestant country and the people would not easily be led to the Church of Rome. Still, a King could do much.

Charles knew that Louis wanted England to join forces with him for an invasion of Holland, and Charles to make public his conversion to the Roman Catholic Faith; he wanted the Church of England abolished and England to return to Rome. For these concessions he was ready to make Charles his pensioner, and was ready to supply men and arms should the English reject the Catholic faith.

Minette would soon arrive in England to persuade her brother, for Louis knew that Charles found it difficult to refuse the women he loved what they asked; and without doubt he loved his sister, perhaps more deeply—certainly more permanently—than any other woman.

So much desperately needed money, mused Charles, and all for a Mass.

He sent for James, for this was a point wherein they would be in sympathy, and as his brother came into his apartment Charles was struck by his pallor.

“You are not looking well, brother,” he said. “I trust naught ails you?”

“I was never the same since I threw off the pox, and since the boy went …”

Charles nodded. “And I hear sad news of my good sister Anne.”

“She spends most of her time at Richmond with the children now.”

“And on her knees, I hear.”

James looked at his brother sharply.

“Ah,” went on Charles, “it is unlikely that I should not be informed on such a matter. So the Duchess has now completely gone over to Rome?”

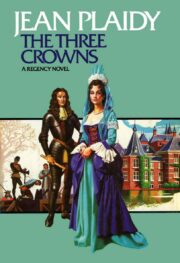

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.