The blood had been washed from the Duchess’s face and hands; the sheets had been changed and she lay back while the Duke sat by her bed watching her.

“I fear,” said James, “that you have had this evil dream because Margaret Denham has been much on your mind.”

“She will not be forgotten it seems.”

“Nonsense. In a few months no one will remember her name.”

“Oh, James, make sure that there are no more Margaret Denhams.”

“My dear, how could I know that she would die in such circumstances?”

“It would have been of no account how she died if you had been a faithful husband to me.”

James sighed. “That is a matter we have discussed many times before, Anne. Let us have done with it.”

“It was as though she were here … in this room, James. As though she upbraided me.”

“You are not well. I have noticed that you have been looking tired of late.”

“There is nothing wrong with me.” Her hand imperceptibly touched her breast.

He leaned over and kissed her. “Oh, Anne,” he said, “if you were a humble merchant’s wife and I that merchant, it would have been different.”

“Being humble would not have changed your nature, James. There is a wildness in you … a need for women which is paramount to all else. You inherited it from your grandfather who, I have heard, had more mistresses than any King of France. What more could be said?”

“Yet,” said James, “there is no other that can claim my heart but you.”

“Spoken like a Stuart.” She laughed. “I’ll swear Charles is saying the same at this moment to one of his ladies.”

“But I mean it, Anne.”

“Stuarts always mean what they say … when they say it.” She lay against him. “It is good to have you with me, James. There is much of which I would speak to you.”

He kissed her and she was aware of the passion which was so ready to be aroused. Perhaps it was not for fat Anne Hyde, the mother of his children (two only of whom were strong and healthy and they girls), no, not for that Anne Hyde, but for the young girl whom he had met and loved at Breda, the girl whom he had seduced, making marriage a necessary but still a greatly desired event.

This was how it should have been for all the years of marriage—James forgot his mistresses; Anne forgot the recurring pain in her breast, the secret visits to the priest. Though fleetingly she assured herself that soon she would discuss her views with James, for she wanted to share her faith with him as she had shared her life.

But for that night they were merely lovers as they had been in the days at Breda.

After that night the Duke and Duchess of York were more often in each other’s company than previously. The Duchess’s influence over her husband appeared to have increased and although James visited his mistresses occasionally, he was devoted to his wife. As for Anne, she was more interested in discussing religion than any other subject and it was remarked that in conversation she seemed inclined to veer toward Rome.

James’s great interest was, as it always had been, the navy; he had won great honors at sea but when de Ruyter, the Dutch commander, sailed into the Medway and destroyed several of the King’s ships, including the Royal Charles, and then had the temerity to sail up the Thames as far as Gravesend, the efficiency of the Duke of York began to be doubted.

Clarendon, who had once seemed all powerful, was in exile; and now the Duke of York, whose wife was suspected of being a Catholic, was showing signs of following her lead.

In the midst of rumors and suspicions James had a slight attack of smallpox and as soon as he was ill his virtues were remembered rather than his faults; the Duchess who was expecting a child in three months’ time was constantly with him; and they both prayed for a son because Charles was hinting once more that he would like to legitimatize Monmouth.

Monmouth was the darling of the King and the Court. He often visited Richmond, to the delight of Mary; but what he was most interested in was the health of the Duchess. She had been looking strained and tired of late; her skin was growing sallow, and some of her attendants had reported that she was suffering occasional pain.

If the child was stillborn, reasoned Monmouth, his father might well prevail on his ministers to have him, Monmouth, legitimatized.

“And that,” he repeated to himself again and again, “would be the greatest day of my life.”

He could never see the Crown and the ceremonial robes without picturing himself wearing them and thinking how well he would become them! If only James had no children! The little Prince was sick and it was hardly likely that he would live. The girls were so healthy though—particularly Mary. Anne of course was such a little glutton that she might burst one day through overeating; she was like a ball as it was. And the Duchess did not look like a healthy mother-to-be. There was great hope in Monmouth’s heart that summer.

He was looking about him for friends who would help him to what he so passionately desired, men such as George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham—a wit, a rake, but a shrewd man, and one of the King’s favorite companions. He was a man fond of intrigue and had recently hoped to make Frances Stuart the King’s mistress and govern through her. No plan was too wild to interest him. He had just left the Tower whither he had been sent for fighting with the Marquis of Dorchester—an ungainly scuffle, with Buckingham taking possession of Dorchester’s wig and Dorchester pulling out some of Buckingham’s hair in retaliation. Later he had again been sent to the Tower for, it was said, dabbling with soothsayers concerning the King’s horoscope. But Charles could always find reasons for forgiving those who amused him, and he did not like such as Buckingham to leave him for too long at a time.

Buckingham was no friend of James, Duke of York. Could it be that he might be a friend of Monmouth’s?

He must find powerful friends. Clearly if the King had no male heir and James neither, it would be to his benefit; and when the King died and it was James’s turn? Well, would the people of England accept a Catholic King? Monmouth was certain they would not. Therefore he would show them that he was staunchly Protestant. He would begin now, laying his plans, forming friendships with men such as Buckingham who would be of use to him, letting the people know that if they did not want a Catholic King there was a good Protestant waiting to serve them—the only reason why he was not proclaimed the heir, being the fact that his father had failed to marry his mother—and some said that this was a falsehood.

All through those summer months Monmouth waited for news of the Duchess’s accouchement. It was a sad day for him when he heard that she had been brought to bed of a boy.

The Duchess of York was on her knees in the small antechamber and with her was Father Hunt. They prayed together for a while and when she rose the priest said to her: “I thank God that you are now rid of doubt.”

“I thank Him too,” she answered. “I will never now falter. Coming to understanding has given me great comfort.”

“You will find greater comfort.”

“Father, this is something I have told no one yet. I fear I have not long to live.” She touched her breast. “I have a pain which grows more agonizing with the passing of the weeks. I have known others who have had such a pain. It increases and in time kills.”

“Then, Your Grace, it is good that you have come to understanding in time.”

She bowed her head in assent. “Father, I have talked to my husband of the doctrines of our Church and I know him to be interested. Before I die I should like to bring him to the truth. There are also my children.”

“Your Grace, this is a matter for great delicacy. Speak to your husband, but use caution. Your children, it would be said, belong to the state and as this state is not yet ready to come to the light, it is necessary to exercise great caution.”

“Rest assured I shall do so,” replied the Duchess.

She left the priest and went to her apartments; and later when the Duke came to her she told him that she wanted to speak to him very seriously.

“James,” she said, “I have become a Catholic.”

He was not surprised; she had betrayed her leanings to him many times. In fact, the Catholic religion appealed to him; he liked its richness, its pomps and mysteries. He had often thought how comforting it would be to confess his sins and receive absolution; and when one sinned again to know that one had but to repent and do penance to wipe out the sin. The less colorful Protestant church was not so appealing. His mother had been French and a Catholic; his grandfather had been a Huguenot, it was true, but he had changed his religion when it was expedient to do so with the remark which had never been forgotten that Paris was worth a Mass. Charles was like that. He would change his religion for the sake of peace. But James was different. He was idealistic and a man who could not see danger when it was right under his nose. Perhaps he even found a thrill in courting danger. Perhaps the very fact that he knew the disquiet which would arise through the country if one so near the throne became a professed Catholic, made the proposition the more irresistible.

He took her hands and they talked long and earnestly.

“I will instruct you in the doctrines, James,” said Anne. “I am sure you will want to be converted as I have been.”

It was a new bond between them. Since his attack of smallpox they had become closer, and when they had lost their newly-born son their grief had been great, but it was a shared sorrow and his amorous adventures outside the marriage bed had never been fewer.

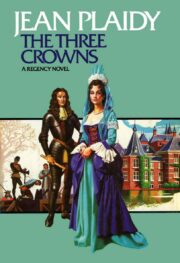

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.