“Surely I am keeping you from your duties.”

“I am only preparing to hear Confession.”

A sudden idea came to Buford. “Father, would it be possible? Would you hear my confession?”

Father Amadie frowned. “My son, are you Catholic?”

Buford shook his head. “I am no Papist. I mean, no, I am not Catholic.”

“Do you understand what you ask of me?”

“Father, my mother was a French Catholic. My aunt was of your faith, and she would take me to Mass when I was young. I know your sacraments; I know what they mean.”

“Then you know that I cannot give you absolution,” Father Amadie explained gently.

“I know, but… but my heart is heavy with regret. It would be a comfort. Please, I know I ask much of you.”

The priest reflected for a moment. He knew he should ask the English Protestant to leave, for to his bishop, the soldier was no better than a heretic. He knew countless Catholics had died at the hands of the Church of England during the Reformation and that Catholics still did not have full rights in Britain.

Father Amadie believed in God and His Holy Church with all his heart, yet he knew that both sides had engaged in religious warfare. The Inquisition in Germany was matched by the Inquisition in Spain. Catholics and Protestants had heaped unspeakable acts upon one another in the name of salvation. Did being right justify such behavior?

Amadie had joined the Church to serve God and the people—and serve he would. Besides, what his bishop did not know would not hurt him.

“Come with me, my son.” He gestured to a side wall of the church where a small door was flanked by two curtains. The priest opened the door and sat in his familiar chair, where he heard so much of the pain of this world. By the time he slid open the window, the English colonel had already taken his position on the kneeler.

Buford bowed his head. “Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned.”

Buford returned to his room to write a letter.

My dearest Caroline,

I take up pen to write to you, deeply mortified at the pain my unjust and unworthy letter must have caused you. Destroy it at once, I beg you, my dear wife! If I could reach across the seas, I would snatch up that evil document and consign it to hell! What a wretch you have married!

Too good, too excellent wife, how could I write such lines to you? Before me are the results of your most faithful labors. I feel unworthy to touch them. But read them I must, for thoughts of you are in my every sleeping hour—and waking hour, too.

I know you wish news of me, your most undeserving husband. I am well in body but ill in spirit. If I were a selfish man, I would beg you to fly to my arms and comfort me. But I cannot—I will not. I am happy you are safe in England, and I am pleased to know you have found a home with my most excellent family. Your letters are a godsend to my soul.

My equipment safely arrived. Thank you for your kind attention to that. The men, all veterans, were ill-prepared for battle when they disembarked, but constant drill has sharpened them like the edges of their sabres. They will be ready for whatever Providence brings.

My love, you write that our family is increasing. What happy news! That God would so smile upon us! I wish I could be there to share this time with you, my dearest one. You write that your belly is growing; nothing in this world sounds so beautiful! Know that I send kisses to that wonderful roundness, that evidence of our love, and its mother too. You say you wish it to be a boy. I would be as proud as a prince to have a son by you, but I cannot help but wish that it be a lovely girl instead with her mother’s looks. That way I might have two Carolines to spoil.

I think your idea to remain in London is a good one, for nowhere else in the kingdom boasts better physicians. I beg you to take care of yourself—but who am I to tell you your duty? You have proven yourself to me a hundredfold.

I must admit something to you, dear Caroline. When I first met you, while I was pleased with your outward appearance, I was only looking for a mistress for my house. I never thought I would fall in love with my future wife. But God in heaven is merciful and has given me a great gift—the sweetest, wisest, kindest, loveliest woman any man could ever wish for.

I love you, Caroline. I love your loving soul. I love your excellent mind, so wise and sharp. I love your form and figure. Oh, how my dreams of you keep me up at night! I love your eyes—so full of expression. And I love your lips—for your sharp, amusing words and for your sweet kisses.

I do not deserve you, my wife. You should have married better than I. I know my faults, and I will strive for the rest of my days to improve myself, to make myself worthy of calling you my beloved wife and lover and mother of my child.

Adieu, my dearest love. I shall write again as soon as time permits. I shall sign this as you have done so consistently,

Rwy’n dy gari di,

JOHN

Letter finished, Buford needed it to arrive in England as quickly as may be.

“You want me to do what?” cried Major Denny.

“Come, man, I am not asking you to do anything illegal,” pleaded Buford. “A small thing—what is that between friends?”

Denny looked at the colonel. “You want me to enclose a personal letter in the official pouch to London, and you call it a small thing? Forgive me, Colonel, but I would like to know what you would refer to as a great favor!”

“You can do it, can you not? You have a friend on the staff who will either post it or deliver it?” Buford begged.

Denny thought. “Yes, Castlebaum would do it, especially if there was something in it for him. It will cost you a half-crown, sir.”

“Done and done, sir!” cried Buford as he shook the man’s hand. “Here is the money. I call it a bargain!”

Colonel Fitzwilliam watched his men practice, and it did not make him happy.

“What do you call that, gentlemen?” he bellowed. “You ride in that lackadaisical manner against the French, and they will cut you to pieces. Show some spirit! Do the drill again!”

Four at a time, the forty riders of the third squadron took off down the training course, while the other nine squadrons watched. The course laid was a fifty-yard dash to a straw bundle, then halting at a post wrapped in cotton and burlap, then a final gallop past another post, this one uncovered. All the time the troopers were to slash at the targets with their swords. Most did the drill correctly, if cautiously. None did it quickly.

“Hell’s fire! Must I do everything myself?” Fitzwilliam cried. “Stand clear!” He drew his sabre and readied his mount. With a drive of his spurs, the horse shot forward.

“ARRRGGHH!” he screamed as he headed down the left-hand side of the course, leaning over the horse’s neck and pointing the sword forward. At full speed, he cut at the haystack with all his might, straw flying everywhere. Pulling back at the reins, he expertly pivoted and dashed to the second target. His mount danced about the post as Richard slashed at it repeatedly. Then in a blink, he was off again, his blade this time held at an angle to his body. It made a satisfying thunk as it struck the last post. Reaching the end of the course at top speed, he halted in a cloud of dust.

“Time!” he called.

His aide checked his pocket watch and informed the rapt audience that the colonel had bested their top performance by ten seconds.

“There!” Richard called out, breathing heavily. “If an old man can do that, you can certainly do better. Do the drill again, and a pint of ale to any man who bests my time by twenty seconds!”

A cheer went up from the troopers. “I will be drinking your beer soon, Red Fitz!” cried one unnamed rider as he took off down the course.

Richard could not help grinning at the use of the nickname by which his men referred to him, usually when he was out of earshot. By the time the exercise was over, Colonel Fitzwilliam was poorer by a gallon and a half.

Happy to have found something to motivate his men, he turned to his aide. “A barrel of Belgium beer to the squadron with the best average time.” The aide grinned and left to deliver the message.

Richard was satisfied. His troopers would be ready.

London

While Caroline performed at the pianoforte, Marianne hid her disquiet as she had tea with Anne, Mrs. Albertine Buford, and Rebecca. Marianne knew that Caroline was unhappy, for while she played with great skill and technique, there was a want of feeling. Her friend was mechanically going through the motions.

Caroline finished and turned to her guest. “Do you play today, Marianne?”

“I thought you were my friend,” Marianne exclaimed.

Caroline was taken aback. “Whatever do you mean?”

Marianne smiled at Mrs. Buford and Rebecca. “She would have me, with my meager talents, follow such a lovely performance. For shame! I shall be thought as the most rank beginner in comparison, I am sure.”

For the first time that day, Caroline allowed a smile to adorn her face. “Meager talents, indeed! Come, Marianne, you leave tomorrow. I would love to hear you play once more.”

The guest sighed dramatically. “Oh, very well, if you insist.” Privately, Marianne was very pleased with her efforts to lighten Caroline’s mood. She sat before the instrument and started into a light country air while Caroline took a seat next to Anne.

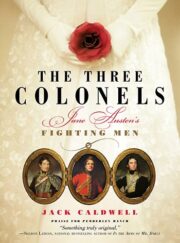

"The Three Colonels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Colonels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Colonels" друзьям в соцсетях.