Later, as she prepared for bed, Mrs. Jenkinson thought over the last two years. For the twenty years since her husband’s untimely death, she had been Anne’s governess and companion and had despaired of ever seeing her young charge take her rightful place in the world. Anne had been a sickly child; her constant cough and runny nose prevented her from developing her talents and kept her shut up in her nursery and rooms for most of her life. It was hard to imagine the daughter of a baronet not learning to sing, or play, or dance, or draw, but at least Anne could improve her mind. Reading was her only joy—that was, reading what Lady Catherine would allow.

Mrs. Jenkinson was an obedient sort, taught never to question her betters, but her heart went out to Anne. She grew to love her like a daughter—the daughter she would never have. Therefore, she would do whatever she needed to do to help Anne survive. For twenty years, Mrs. Jenkinson followed Lady Catherine’s commands to the letter, no matter how foolish or cruel. She would keep her girl alive, no matter how much her heart would rebel at her instructions.

Three years earlier, Fitzwilliam Darcy upset all of Lady Catherine’s plans and dreams by marrying Miss Bennet. Mrs. Jenkinson by then knew her girl’s mind—knew she did not love Darcy in that way—and that Anne was relieved of her fear of a forced, arranged marriage.

Then, two years ago, Mrs. Jenkinson’s old aunt gave her some advice. Her aunt was wise in the old ways. She knew things—things that doctors and other men of science could not explain. Mrs. Jenkinson had thought over her advice for a long time. Then, one night, as she watched Anne’s cough develop into yet another fever, she made up her mind.

That night, two years ago, she committed murder.

Richard lay on his bed, jacket off, hands behind his head, when there was a knock at the door. “Enter,” he called out.

The housekeeper, Mrs. Parks, came in the room with a tray of chicken, cheeses, and bread. A bottle of Madeira was brought as well.

“Thank you. Please set it down on the table there.” He rose and crossed over to the table. Popping a bit of cheese into his mouth, Richard noted that Mrs. Parks had not left. She stood in the middle of the room, looking expectantly at him.

“Mrs. Parks, I trust I find you in good health?”

The housekeeper’s unreadable countenance did not change. “Well enough, I thank you.”

“The… eh… staff—everyone getting along?”

“Perfectly, sir.”

Richard was uncomfortable. He remembered Darcy’s words: “Trust Mrs. Parks. She can be of invaluable aid to you.” Could Darcy have meant this stone wall? If Richard were back in his regiment, he would know how to deal with this. But he was not; this was a household and not his household.

Clearing his throat, Richard asked, “Mrs. Parks, is there anything you wish to tell me?”

In an emotionless voice, the housekeeper answered. “Everything in this household is as you see. I have no complaints to report. I very much enjoy my position here. Is that all?”

The slight air of insubordination was too much for Richard. Civilian or not, he knew of only one way to deal with this. Drawing himself up to his full height, he fixed his most severe glare on the woman—a glare that had caused not a few lieutenants concern over soiling their breeches. With the voice of a king’s officer who had seen war and worse, he said, “I am glad to know of it. I will surely keep those sentiments in my mind.” He allowed the pause to hang in the air before finishing. “That is all. You are dismissed.”

Richard’s quiet yet forceful tone lashed across the woman. It was a moment before Mrs. Parks could manage her curtsy and exit the room. No sooner had the housekeeper left, than Richard unhappily threw himself into the chair.

The interview had not gone well. Richard had learned nothing about the problems within the manor house, and that left him frustrated. He felt that he could not let down his father—or Darcy—or Anne.

Anne? He frowned. Where did that come from?

Dismissing the thought as quickly as it came, Richard returned to his meal with little appetite.

Mrs. Parks walked down the hallway towards her own quarters, fighting the small smile that threatened to come to her lips. She knew it would take a gentleman with extraordinary strength of character to stand up to the Mistress and set things right. She had quite despaired since Mr. Darcy’s banishment from Rosings and had no faith in the happy-go-lucky soldier son of Lord Matlock.

But perhaps she was wrong. The young man had shown some steel beneath his genial exterior.

She could not stop herself from thinking that there might be hope for them, after all.

Anne de Bourgh snuggled deeply into her bedcovers. It was one of her favorite things to do on a cold winter’s night. It was a pleasurable end to an eventful day.

Anne recalled how pretty Kitty looked—so happy, shy, and excited, all at the same time. Mr. Southerland walked around the entire time with a rather silly half-grin on his face, as if he could not believe his own good fortune. Anne wished the couple well, for she and Georgiana had become much attached to the girl.

Georgiana would be next, she imagined. How lovely a wedding at Pemberley would be! Perhaps Mr. Southerland would do the honors. Oh, how that would upset Mr. Collins! He still fretted over Elizabeth and Darcy’s choice of a bishop. On and on her thoughts flew, ignoring the fact that Georgiana had no beau.

Anne loved to think of other people’s weddings, for she expected none for herself. It was only in the last two years that she was healthy enough to overcome her mother’s reluctance and spend time away from Rosings, but liberation from her gilded prison was limited, as was her company. Only to Matlock and finally Pemberley was Anne permitted to go.

Anne was realistic about marriage. She was not too old—yet—but she had no talents, no accomplishments, and no beauty. How was she to compete against the ever-replenishing pool of eligible young misses in society?

No, she was resigned to being the beloved, unmarried aunt to the Darcy and Fitzwilliam children. Anne’s thoughts became melancholy as she began to drift off to sleep.

“I think the time is quickly coming that you will not need old Mrs. Jenkinson to fuss over you. You will have some strapping young man for that, God willing,” Mrs. Jenkinson had told her.

No, dear Mrs. Jenkinson, there will be no young man for me, Anne thought to herself. The only marriage that could have happened did not, thank heaven, because Darcy was wise enough to marry for love. And I am the same. I will only marry for love, and therefore, I will never marry, for I love in vain.

All of her life, Anne’s mother wanted her to marry Fitzwilliam Darcy. How would Lady Catherine react if she knew her daughter did love Fitzwilliam—just the wrong one?

Chapter 10

Fitzwilliam arose early, as was his routine enforced by years in camp. After breakfast, he joined Rosings’ steward in the library to review the condition of the estate.

Hours later, the steward left a very bewildered colonel in that room. Richard sat before a desk strewn with maps, contracts, agreements, surveys, estimates, and at least a dozen documents he could not understand. He had been prepared for work, but this was so far out of his experience that at first he felt a sense of drowning. Half of what the steward said sounded like gibberish. Finally, after giving over his pride, he began to ask what he thought were very simple questions, but the steward answered them fully, never showing in his countenance that he thought the colonel was a simpleton. No, in fact, he treated Richard with the greatest patience and respect and readily agreed to ride the property with him the next day.

As for Fitzwilliam, the lessons in estate management his father insisted he take had finally come back to him about an hour into the interview. Richard was still confused over many points, but the conclusion was clear: Rosings was failing. The realization of the true condition of the place weighed heavily on him. Richard wished that his father, his cousin, or even his brother, the viscount, were there to help him. But no, it was not to be.

For heaven’s sake, man, what are you about? You have led a thousand men into the blazing guns of the French. You can do this. Richard looked at the piles. It is simply a matter of organization. A table—that is the very thing I need. Richard drew a blank sheet of paper from the desk drawer and began writing.

“Richard?”

Richard looked up and saw Anne peeking around the library’s door, dressed in a heavy winter cloak.

“Come in, my dear.” He rose, crossed to her, and took her hands. “Anne, have you just come in from outside? Your hands are like ice! Come, sit by the fire.” He escorted his cousin to a chair by the fireplace, despite her protests.

“I am not chilled at all. I rather enjoy my winter walks. The air is so invigorating!”

“Really, Anne! Think of your mother. She would be distressed at this behavior.”

Anne’s eyes went wide, and her good cheer fled. “Oh, please do not tell Mother! She would certainly forbid me my walks!”

Richard’s self-righteous concern faded at the sight of his cousin’s distress. “Never fear, my girl. I will not reveal your secret. Mum’s the word.” He absently patted her hands.

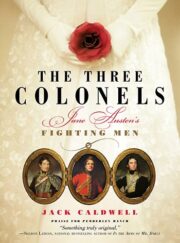

"The Three Colonels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Colonels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Colonels" друзьям в соцсетях.