Edward kissed her hand. She was an unusual woman. He was drawn to her, partly for herself and partly because she was Elizabeth’s mother. And she was his friend. Somewhere in his mind was the thought that she would help him if she could.

She was implanting that thought there, trying to draw him into the family, visualising a glorious prospect for Elizabeth without giving him a glimmer of what it was ... in fact, she scarcely admitted it to herself, because it seemed impossible.

‘We shall serve you,’ she said. ‘Elizabeth will be your faithful subject but never never anything else.’

‘My lady, I believe you to be my friend. You will make my cause yours.’

‘The King’s cause shall be mine,’ she answered solemnly. ‘Bless you, my bonny lord. I shall wish for you everything that will serve you best.’

He rode somewhat disconsolately away from Grafton. He was beginning to believe that Elizabeth meant what she said. She was a virtuous woman. She would not take a lover outside marriage.

Marriage! But he was the King. That was impossible.

Edward was so quiet in the days that followed his visit to Grafton that his friend Hastings was quite concerned for him.

He enquired how the King had fared with the beautiful widow lady.

Edward shook his head.

‘She was a disappointment,’ said Hastings. ‘I thought she might be. There was a frigidity in her. A plague on frigid women.’

Edward was not pleased to hear Elizabeth discussed lightly as though she were the participant in some ordinary brief affair.

He said shortly: ‘She is the most beautiful woman I ever saw.’

‘Oh, I grant you that. But I personally have no fancy for statues.’

‘It would avail you nothing if you had,’ said Edward shortly.

‘Do you mean to tell me that it did not come to fruition?’

‘Lady Grey is a virtuous widow.’

‘A plague on virtuous women ... widows especially.’

‘I have no wish to discuss the Lady Elizabeth Grey with you, Hastings.’

God in Heaven, thought Hastings, what has come over him? The lady refused him. It must be the first time that has happened. Well, it will do him no harm. But it has affected him considerably.

He did not mention the visit to Grafton Manor after that.

At Westminster the Earl of Warwick was impatiently waiting. Edward always felt a slight deference in the presence of Warwick, who was known by the soubriquet of Kingmaker. Everyone was aware, and Edward would be the first to admit it, that but for Warwick’s prompt action in marching on London after the Yorkist defeat in the second battle of St Albans Edward might not be king today. Warwick was not going to let anyone forget it. Nor did Edward want to. He was grateful for his friends and Warwick had been his hero from childhood. Ever since his early days in Rouen where he and his brother Edmund had been born he had known he was destined for greatness. His mother Cecily Neville had made him aware of that; and Warwick’s father was her brother, so there was a bond of kinship between him and the great Earl, and Warwick had always been part of his youth. Warwick was fourteen years older than Edward and had seemed almost godlike to the boy.

If Edward had the bearing of a king, Warwick had an even more powerful image. Kings were glorious but they depended on kingmakers and Warwick fitted without doubt into the second category.

Warwick spoke with authority. Ever since the first battle of St Albans which had been won by his strategy he had been distinguished throughout the country; and when he had become Captain of Calais and had held that important port for England and the Yorkists, he had won the hearts of the English by his exploits against the French; he had seized their goods and played the part of pirate-buccaneer with such verve that he was accepted as a great hero, one of that company of men of which England was in need since the disastrous losses in France.

The Earl had never been one of Edward’s boon companions such as Hastings and men of that kind. It was a serious relationship between them. Warwick did not frown on Edward’s adventures. They had kept the young man occupied while Warwick ruled. That was all very well when Edward was in his teens, but he was now twenty-three years of age and Warwick had plans.

They embraced when they met and Edward’s affection for his cousin was obvious.

‘You are looking pleased with yourself, Richard,’ he said. ‘What have you been doing? Come, tell me. I know you are longing to.’

‘I am as you notice rather pleased with my negotiations at the French Court. We must have peace with France and, Edward, you must marry. The people expect it. They love you. You look like a king. They smile at your pursuit of women. They expect a young king to have his romantic adventures. Not too many though, and they want a marriage. The people want it, the country wants it ... and that is a good enough reason. What say you?’

‘Well, I am not averse.’

Warwick looked at the King with affection. He had made him and he would keep him on the throne. Edward was amenable. He was the perfect puppet; and while this state of affairs remained Warwick could rule without hindrance. It was what he had always wanted. Not for him the heavy crown of office; how much more comfortable to rule behind the throne, to be the Kingmaker rather than the King. And Edward was the perfect tool. His easy-going, pleasure-loving nature made him that.

‘Then let us get to business. Do you realise you are one of the most eligible bachelors in the world? Not only are you King of England but the whole world knows that in addition to your crown you have an outstanding charm of person.’

‘You flatter me, Richard.’

‘Never will I do that. But let us face facts. I have become on excellent terms with Louis. I can tell you he treats me as though I were a king.’

‘Which you are in a way, Richard,’ said Edward.

Warwick looked at him sharply. Was there something behind that remark? Was Edward growing up, resenting someone else’s use of the power that was his? No, Edward was smiling his affable, good-natured smile. He was merely reminding Warwick of his power and implying that he felt it was right and proper that it should be his.

‘I have decided against Isabella of Castile. Her brother is eager for the match. He is impotent, poor fellow and it is certain that there will be no children, so Isabella would be the heiress of Castile.’

‘But you have decided against her.’

‘I think, Edward, we have a better proposition. My eyes are set on France.’

‘Ah yes, you are on such good terms with Louis.’

‘We must have peace with France. The best way of making peace is through alliances as you well know. So I turn away from Isabella, and back to France. Louis suggests his wife’s sister, Bona of Savoy. She is a beautiful woman and one who will delight you, Edward. Louis and I agreed that we must not lose sight of the fact that you must have an attractive wife. You are very well experienced in that direction and we want you to be happy.’

‘You are most considerate,’ said Edward.

‘She is a very beautiful girl and it will be a successful match. The great thing is heirs. We must have an heir to the throne. The people are always uneasy until they can see their next king growing up ready to take his popular father’s place.’

Edward was scarcely listening. He was thinking of Elizabeth. What a wonderful project it would have been if she had been a Princess of France or Savoy or Castile! How joyously he would have contemplated his marriage then, for of course he must marry. Of course he must produce an heir.

If only it could be with Elizabeth!

‘I see no reason why we should not complete these arrangements with Louis immediately,’ Warwick was saying but Edward scarcely heard him for his thoughts were far away in Grafton Manor.

One of his squires came into Edward’s chamber to tell him that there was a man who was asking for an audience.

‘And who is this?’

‘My lord,’ said the squire, ‘he is a Lancastrian, a traitor who had fought for Henry of Lancaster.’

‘Why does he come here?’

‘He says he has something of importance to say to you.’

‘Ask his name.’

The squire disappeared and came back almost immediately. ‘It is Lord Rivers, my lord.’

‘Ah,’ said Edward, ‘I will see him at once.’

The squire replied: ‘My lord, I will see that the guards are within call.’

‘I do not think you need to go to such lengths.’

The squire bowed, determined to in spite of the King. He was not going to put Edward in any more danger than could be helped.

He hesitated.

‘I have asked you to bring Lord Rivers to me at once,’ Edward reminded him.

‘My lord, forgive me, but should there not be guards in this very chamber?’

‘No. I do not think Lord Rivers has come here to harm me.’

At length Lord Rivers was brought in. Undoubtedly he was handsome. Edward had been learning something about the family since the encounter under the oak. So this was the man for whom that rather enchanting Jacquetta had defied convention and given him fourteen children to boot, and among them the delectable Elizabeth.

‘Well, my lord,’ said Edward. ‘You wished to speak with me?’

‘I have come to offer you my allegiance.’

‘Odd words for one who has supported the cause of my enemies for so many years.’

‘Times have changed, my lord. I was for Henry because he was the anointed king. I do not change sides easily. But Henry is little more than an imbecile; he is far away somewhere in the North in hiding, but if he returned he could never give England the rule she needs. And now we have a king who has more claim to the throne than Henry had. I shall work now to keep us in this happy state.’

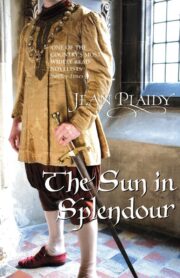

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.