It was the greatest eclipse of the sun which the people of England had ever seen and they thought it must have something to do with the passing of the Queen.

Anne was unaware of it. She knew only that Richard was with her, holding her hand and that she was slowly slipping away from him.

‘Richard ...’ she tried to say his name.

He bent over. ‘Rest, dearest,’ he said. ‘It is best so.’

‘Soon I shall be at rest,’ she murmured. ‘Soon I shall see our son ... Oh Richard, I shall be with you ... always ...’

His cheeks were wet. He was surprised. It was long since he had shed a tear.

An utter desolation had come to him.

She had gone ... this companion of his youth, this faithful wife; the one he had loved even more deeply than he had loved his brother.

There would never be anyone else. He did not change. Loyalty bound him.

The rumours were at their height. He was going to marry his niece.

Elizabeth of York was agreeable and Elizabeth Woodville would welcome the marriage. It would settle differences. The Woodvilles could hardly be against a King who was the husband of one of their daughters.

Marry his niece! It was incest.

Typical of him, they said. He was without scruples.

Richard knew that he must think of marrying.

Rotherham had pointed out that a King without an heir was storing up trouble. He should marry. People were saying that his niece was a strong and healthy woman.

‘She is indeed,’ replied Richard, ‘and I doubt not that she will bear strong children when the time comes.’

Rotherham reported to Morton that the King was contemplating marrying his niece.

Sir William Catesby and Sir Richard Ratcliffe took an early opportunity of speaking to the King.

He must not marry Elizabeth of York. They themselves were very anxious to keep out the Woodville influence for they feared it would go hard with them if ever that family crept back into power. They had placed themselves on Richard’s side so clearly against the Woodvilles. But that was not all. They served Richard faithfully and they feared that a marriage with his niece would damage his reputation even further. They had no doubt that the Pope could be induced to grant a dispensation. But it would be wrong and if Richard was going to look for a bride he must do so elsewhere.

‘My dear friends,’ said Richard, ‘you have no need to warn me. I had no intention of marrying my niece. It is just another of those evil rumours which have suddenly started to circulate about me.’

Catesby and Ratcliffe were greatly relieved.

Richard smiled at them. ‘Surely you did not believe I would marry my niece? I tell you this, I am in no mood for marriage. I still mourn the Queen and have other matters more urgent. Spring is coming. The Tudor is certain to make an attempt some time this year.’

‘That’s so,’ said Catesby, ‘but all the same I should like to find the source of these rumours.’

Richard sighed. ‘My good friends,’ he said, ‘I agree with you. It is the insidious enemy who can harm us more than the one who comes in battle. I long for the day when I shall face the Tudor on the battlefield. I pray God that the task of taking him may fall to me.’

‘In the meantime, my lord,’ said Ratcliffe, ‘we must put an end to this rumour.’

‘I will send Elizabeth away from Court,’ said Richard. ‘It is not fitting that she should be there – in view of the rumours – now that the Queen is no longer with us.’

‘Where should she go, my lord?’

‘Why not to Sheriff Hutton. She will be away from the Court there. One or more of her sisters could go with her. It shall be for them to decide. My Clarence nephews are there, Warwick and Lincoln. She will be company for them and they for her. Yes, to Sheriff Hutton.’

Catesby and Ratcliffe were well pleased. They hoped they had stopped the rumours about Richard and Elizabeth.

Chapter XVII

BOSWORTH FIELD

August had come and Richard knew that across the Channel plans were coming to a climax. It seemed certain that Henry Tudor would attempt a landing.

Richard was prepared. He was feeling philosophical. Soon the test would come and it was going to be either victory or death for him, he knew.

He faced the future with a kind of nonchalance. He had lost his wife and son. There was nothing left but to fight for the crown.

If he defeated Henry Tudor he would plan a new life. He would try to forget the sadness of old. He would try to be a good King as his brother had been. But that could not be until he had cleared the country of this evil threat of war.

Wars had clouded his life. These incessant Wars of the Roses. He had thought they were over – all had thought so when Edward rose so magnificently out of the horrors of war and took the crown. If Edward had lived ... If his son had been a little older ...

But it had not been so and now he was faced with this mighty decision. He would do his best and he would emerge from the struggle either King of England or a dead man.

At the end of July Thomas Lord Stanley had come to him and asked permission to retire to his estates. He was very suspicious of Stanley. Stanley was a time-server. He was a man who had a genius for extricating himself from difficult situations. Such men were born to survive. They lived by expediency. They swayed with the wind. Richard had little respect for Stanley and yet he needed his help.

He had been arrested at the time of Hastings’s execution but after a very short time had been freed, in time to carry the mace at Richard’s coronation.

He had married Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry Tudor, but he had continued to serve Richard.

Richard did not trust him but he was too important to be ignored and it seemed to the King that to have him close at hand was better than to spurn him and send him right into the ranks of the enemy.

That his wife had played a part in the Buckingham insurrection was undeniable. When Buckingham had been beheaded Stanley had expressed his agreement that the Duke had deserved his fate. It would have been a different story, Richard was fully aware, if Buckingham had been successful.

At the time Stanley had promised to restrain his wife. He would keep her quietly in the country, he had said.

Now he wished to go to his estates as they urgently required his attention.

Ratcliffe and Catesby put it to the King that Stanley could turn against them and the wisest course was to watch him. After all he was married to the mother of Henry Tudor.

‘I know,’ said Richard. ‘If he is going to turn traitor it is better for him to do so now than on a battlefield.’

So Stanley left but Richard said he must leave his son behind to answer for his loyal conduct.

There was nothing for Stanley to do but comply.

And on the seventh of August Henry Tudor landed at Milford Haven.

Richard was at Nottingham when news reached him that Henry Tudor was near Shrewsbury.

He sent for the men he could trust: Norfolk, Catesby, Brackenbury, Ratcliffe.

Stanley had not returned but had sent an excuse that he was suffering from the sweating sickness. His son, Lord Strange, had attempted to escape but on being captured had confessed that he and his uncle Sir William Stanley had had communication with the invaders.

The Stanleys would betray him, Richard thought, as he had known they would.

There was no time to be lost. They must march now and on the twenty-first of August the two armies arrived at Bosworth Field.

Richard spent a sleepness night. He was fatalistic. Would there be victory on the following day? He felt no great confidence, no great elation. Sorrow weighed heavily upon him. But this should be the turning-point. If Fate showed him that he was to go on and rule he would be a great King. He would learn from his brother’s successes and mistakes and he would dedicate himself to the country.

They were there ... his good friends. Brackenbury – his good honest face shining with loyalty – Catesby, Ratcliffe, Norfolk ... the men he could rely on.

And the Stanleys – where were they?

He mounted his big white horse. No one could mistake him. It was indeed the King’s horse. And on his helmet he wore a golden crown.

‘This day,’ he said, ‘decides our fate. My friends and loyal subjects remember that victory can be ours if we go into this fight with good hearts and the determination to win the day. At this day’s end I will be King or a dead man, I promise you.’

The trumpets were sounding. The moment had come and Richard rode forth at the head of his army.

The battle waged. The sun was hot and the Lancastrians had the advantage because it was at their backs. The Stanleys waited. They would decide which side they were on when the decisive moment came. In the meantime they had no intention of fighting for Richard.

They were Henry Tudor’s men and had worked hard for his success. They were ready now ... waiting for the precise moment which would be best for them to depart.

That moment came. The Stanleys were riding out crying: ‘A Tudor. A Tudor.’

Richard heard them and smiled grimly.

Catesby was urging him to fly. He laughed at that. He rode forward brandishing his axe.

He saw Ratcliffe go down and Brackenbury.

My good friends ... he thought. You gave your lives for me ... for truth ... for righteousness ... for loyalty.

A curse on the traitor Tudor!

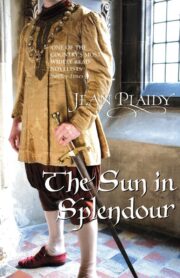

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.