‘Then, Richard, you are King of England.’

‘It would seem so ... if Stillington speaks truth.’

‘Why should he not speak truth?’

‘These are weighty matters. They must be proved.’

‘By God, they must be. And when they are ... This is good news. We shall have a mature king, a king who knows how to govern. There will be no regency ... no protectorate ... no boy King. It is an answer from Heaven.’

‘Not so fast, my lord. First we must prove it. There is much to be done. What I fear more than anything is to plunge this country into civil war. We have had enough of that. We want no more wars.’

‘But you must be proclaimed King.’

‘Not yet. Let us wait. Let it be proved. Let us test the mood of the people.’

‘The people will acclaim their true King.’

‘We must first make sure that they are ready to do so.’

Richard stared ahead of him. He had let out the secret. That it would have tremendous consequences he had no doubt.

It was a devastating discovery. Men such as Buckingham could act rashly. Buckingham’s idea was that Richard should immediately claim the throne. It was what Buckingham would have done had he been in Richard’s position. As a matter of fact Buckingham himself believed that he had claim to the throne – a flimsy one it was true but he made it clear sometimes that he was aware of it.

Richard found himself in a quandary. He wanted to be in command because he knew he was capable of ruling. He had proved that by the order he had kept in the North. He wanted to keep the country prosperous and at peace and the last thing he wanted was a civil war.

The young King disliked him more every day and one of the main reasons was that he was imprisoning Lord Rivers and Richard Grey, and the fact that his mother was in Sanctuary. Young Edward blamed Gloucester for this, which was logical enough; but the King did not understand that his mother and his maternal relations would ruin the country if they ever came to complete power. Lord Rivers was indeed a charming man; he had become a champion in the jousts, he had all the Woodville good looks; he was quite saintly when he remembered to be but he was as avaricious as the rest of the family and he wanted to govern the King. That was what all the Woodvilles wanted. So did Richard for that matter. The difference was that Edward the Fourth had appointed his brother as Protector and guardian of the King for he knew – as Richard knew – that Richard alone was capable of governing the country in the wise strong way which the late King had followed.

Yet the King disliked his uncle. The only way in which Richard could win his regard was by freeing the Woodvilles and to do that he would have to become one of them. There were so many of them and they had gathered so much power and riches during Edward’s lifetime that they would absorb him. He would become a minor figure. He would in fact become a follower of the Woodvilles. It would mean too that he would have to sacrifice his friends – Buckingham, Northumberland, Catesby, Ratcliffe ... It was unthinkable. He ... a Plantagenet to become a hanger-on of the Woodvilles!

The alternative to all this was to take power himself. It seemed to him that he had every right to do this. In the first place he had been appointed by his brother to be the Protector of the Realm and the young King. And now Stillington had come along with this revelation. If it were indeed true that his brother had not been legally married to Elizabeth Woodville he, Richard of Gloucester, was the true King of England.

He could take power with a free conscience. If the people would accept him as their King, he could prevent civil war. He could rule in peace as his brother had done. It was his duty to take the crown. It was also becoming his dearest wish.

But he must go carefully. He had rarely ever been rash. He liked to weigh up a situation, decide on how to act, then consider the consequences – the good and the bad for there were invariably good and bad in all matters.

This marriage with Eleanor Butler would have to be proved. Its consequences would be so overwhelming that there must be no hurrying into a decision on it. He must have time to think on it.

In the meantime there were other pressing matters to be dealt with. Hastings, for instance. Hastings had great power. He had believed him to be loyal. Hastings had warned him of the King’s death and the need to come prepared to London. That had stood him in great stead. Without that warning he might not have heard of his brother’s death until after young Edward’s coronation and that would have been too late. He owed something to Hastings.

Yet Hastings was in touch with Elizabeth Woodville; he had seen the King. Jane Shore took messages to the Sanctuary. They were plotting against him. Richard hated disloyalty more than anything. He had chosen his motto ‘Loyalty binds me’ because it meant so much to him.

If Hastings were deceiving him, he deserved to die, and die he must, for he would be the link between the King and the Woodvilles and if his conspiracy were allowed to proceed it could be the end of Richard. They would have no compunction in beheading him, he knew. They hated and feared him; and the King could give his ready consent.

There must be prompt action. He sent for Richard Ratcliffe, a man whom he trusted. Ratcliffe had been Comptroller of King Edward’s household and his efficient management of affairs had aroused Richard’s interest in him. He came from Lancashire and Richard knew his family in the North. He was a man he trusted.

‘I want you to ride with all speed to York. Take this letter from me and it is to be put into the hands of the Mayor. I want him to raise men and come south to assist me, and to do so with all speed.’

He had written that he needed men and arms to assist him against the Queen and her blood adherents and affinity who, he was assured, intended to destroy him and his cousin the Duke of Buckingham, as the old royal blood of the realm.

‘This,’ said Richard, ‘is of the utmost importance. Delay could cost me my life. Impress this on my good friends in the North.’

‘I will do this, my lord, and leave at once.’

Richard Ratcliffe took the letters and set off.

But Richard of Gloucester knew that he could not afford to wait for help from the North.

It was Friday, the thirteenth of June, two days after Ratcliffe had left for the North. The Protector had summoned the Council to assemble in the Tower for a meeting. There was nothing strange about this for meetings at this time occurred frequently and the Tower was usually chosen for them to take place.

Among those who were to attend were Archbishop Rotherham, Morton Bishop of Ely, Lord Stanley and Lord Hastings.

Richard knew exactly what he had to do.

It was going to be extremely distasteful, but it had to be done. It was either that or his own head and disaster for England as he saw it. So he must not shirk his duty. His brother had not when it came to the point. Clarence had signed his death warrant when he had taunted Edward with the illegitimacy of his children.

Edward had been strong, as Richard must be.

It was a beautiful morning. The sun dappled the water of the Thames as his barge bore him along. He alighted and looked back along the river and then turned to face the Tower. The King was there ... in the Palace. He must remain there until the Protector had decided how best to act.

He met Bishop Morton as he was about to enter the council chamber. He was affable though in his heart he was deeply suspicious of the Bishop. A staunch Lancastrian who had changed sides and served Edward of York when it was expedient to do so. Richard could never like such men; he would have had more respect for him if he had refused to serve Edward and had gone into exile. Not the ambitious Bishop. He was very comfortable in his palace in Ely Place, where he had the most magnificent gardens.

‘I hear your strawberries are particularly fine this year, Bishop,’ said Richard.

‘That’s so, my lord. The weather has been right for them.’

‘I trust you will give me an opportunity to sample them.’

‘My lord, it will be an honour. I will have them sent to Crosby Place. I doubt not the Lady Anne will like them.’

‘Thank you, Bishop.’

Stanley, Rotherham and Hastings had arrived. They all looked relaxed. It was clear that they had no notion yet as to what was about to take place.

Richard veiled the distaste he felt on beholding Hastings. He must have come straight from Jane Shore. He looked jaunty, younger than of late. He was clearly enjoying the company of the late King’s favourite mistress.

The council meeting proceeded and after a while Richard said: ‘My lords, will you continue without me for a while. There is something to which I have to attend. I shall be with you ere long.’ That was the first intimation the members of the Council had that morning that something strange might be afoot. That Richard should suddenly leave them in this way was unusual. It was almost as though he were preparing himself for some ordeal and wished to steel himself before attempting it.

Hastings was thinking that although Richard appeared to be cool he had seemed a little preoccupied. For instance he had not glanced Hastings’s way since he had appeared. But there was all that chat about Morton’s strawberries. That was natural enough. Hastings thought: I imagined this. It is because of Jane. She was worried because he was getting very deeply involved in the conspiracy with the Queen.

Richard had come back. He looked quite different from the man who had left the council chamber. His face was white; there was a look of bitter determination in his eyes.

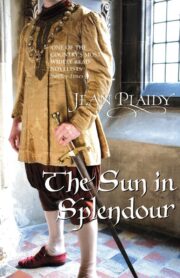

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.