‘I have served you faithfully all the days of my life. Remember that.’

‘I do remember it and it sustains me.’

‘Now, have done with this talk of death. I want to speak to you about Scotland.’

After Christmas the Court went to Windsor but was back in Westminster by the end of February.

Edward had done nothing to change the household of the Prince of Wales. He knew that it would be difficult to explain to Elizabeth. It was still presided over by Anthony Woodville who was constantly with his young nephew. Anthony, disappointed of his marriage to the sister of the Scottish King, had now taken an heiress whom Elizabeth had found for him. This was Mary Fitz-Lewis whose mother was daughter of Edmund Beaufort, second Duke of Somerset. So there was not only money but good family there. However, in spite of his marriage he continued to live at Ludlow with the Prince. Elizabeth would not hear of those arrangements being changed. If Edward had had a shock, so had she and she was more determined than ever that if there were a new king he would be hedged in by Woodvilles.

There would have to be change, Edward supposed. He would see to it in due course.

At the Parliament which was called in January money and supplies were voted for an army which should go into Scotland and the King bestowed on Richard the Wardenship of the West Marches so that he was now indeed the Lord of the North.

February and March were very cold months and towards the end of March Edward went on a fishing trip with some of his friends. The wind along the river bank was piercing and the fishermen in due course decided to abandon the day’s sport and return to a warm fire.

The next day the King was ill. He had pains in his side which made it impossible for him to lie comfortably.

The physicians came to him and declared themselves alarmed by his condition. He had lived so indulgently that he had used up his energies they said and lacked the strength to withstand this violent cold he had caught. It attacked his lungs.

April had come with warmer weather but the King remained in his bed for his condition did not improve. He knew he was dying and that the seizure just before Christmas had been a warning.

Time was slipping away and there was so much he should have done. He was leaving a son, a child little more, vulnerable in a situation which he, in his carelessness, had allowed to arise.

There would be warring factions. There were so many who hated the Woodvilles. While he was there he had kept the peace but what would happen when he had gone?

What must he do? What could he do?

Richard was far away in the North. He wanted Richard here but he did not send for him. He was following his old practice of turning away from what was unpleasant. He was not dying, he told himself. He was going to survive this as he had that other attack.

He would not admit that he was facing death.

He was only just forty years of age. That was not old and he had always been in such good health. Until the seizure no one had thought of him and death in the same moment. He was going to get well.

But in his heart he knew that Death was close and that he must hurry to set things right. Conflict, which seemed inevitable, must be avoided. He sent for those nobles whom he thought might quarrel together. Chief among them was Dorset, his stepson, and Hastings, his greatest friend.

Dorset was on one side of his bed, Hastings on the other and with them were those men who supported them. They looked coldly at each other across the bed and with a gnawing anxiety Edward was aware of their hostility towards each other.

‘My friends,’ said the King, ‘I beg of you forget your differences and work together for the good of my son. He and his brother are but children. They need your help. I beg you give it to them. For the love you have borne me and for the love I have borne you, and for the love that the Lord God bears to us all, I beg you love each other.’

He could not sit up and collapsed on his pillows and the sight of this great strong man thus, moved everyone present to tears.

He begged Hastings and Dorset to clasp hands and to promise as they did so that they would remember their King’s dying wishes.

Hastings was overcome with emotion. There were so many memories he had shared with the King, and to see Edward lying there while life slowly ebbed from him filled him with a sad emotion – not only for the past and the good times they had shared, but for the future. He well understood Edward’s fears for his son.

The boy would have to be protected ... against the Woodvilles.

‘Remember,’ went on the King breathing painfully and finding the utmost difficulty in speaking, ‘remember they are so young, these little boys. Great variance there has been between you and often for small causes.’

He closed his eyes. He was young himself to die. Not yet forty-one years of age and having reigned for twenty-two of them.

But this was the end. There was nothing more he could do.

So on the ninth of April of the year 1483 great Edward died. The news spread through the city of London and on through the country to the blank bewilderment and dismay of the people. They had looked up to him – the great golden King, the rose-en-soleil, the sun in splendour. And now that sun had set.

What next? they asked themselves.

For twelve hours he lay naked from the waist that the members of the Council might see that he was truly dead. Then he was taken to St Stephen’s Chapel where Mass was celebrated every morning for a week, and after that to Windsor and there buried in St George’s Chapel in the tomb which he had had prepared for himself.

The country was stunned. He had been with them so long. They looked to him. They relied on him. He had been among them for so long – their brilliant, splendid, magnificent King.

And what would happen now?

They waited in consternation to discover.

SUNSET

Chapter X

THE KING AND PROTECTOR

When he awoke that morning there was nothing to suggest to the thirteen-year-old Edward that this was going to be any different from another day. Time glided along smoothly at Ludlow. He had come to regard the great grey castle as home and when he rode out in the company of grooms and very often with his uncle, Lord Rivers, he was always delighted to come back to the square towers and the battlemented walls guarded by the deep wide fosse. He loved the Norman keep and large square tower with ivy clinging to it. In the great hall Moralities were performed at Christmas and when his mother came special balls were arranged. He loved to ride out into the town which itself stood on a plateau overlooking hills and dales of considerable beauty. It would be hard, his uncle Rivers had said, to find a more beautiful spot in the whole of England.

The most important person in his life was Lord Rivers, Uncle Anthony, who was so eager to be with him and explain everything to him and was such an agreeable companion. They hunted together, played chess together, and he had been very much afraid when his uncle had recently married – for he had been a widower – that he would lose him.

‘No,’ said Uncle Anthony, ‘nothing would prevent my being with you, my little Prince. You are my first concern.’

So although he had gone away briefly he was soon back and it was as it had been before. His wife would visit them from time to time perhaps but she would want to please her husband and that would mean pleasing the Prince.

If Anthony was his favourite companion and perhaps the most important person in his life, his mother held a special place.

She was so beautiful. He had never seen anyone like her. And she was always affectionate towards him. When she arrived she could look so cold, like an ice Queen, and he liked to watch her when she was greeted by the servants and attendants with the utmost respect because after all she was the Queen; and then she would see him and her face would change; it was like the snows melting in early spring. The colour would come into her face and she would hold out her arms and he would run into them and then he thought he loved her more than he could ever love anyone even Uncle Anthony, although of course he admitted to himself he needed his uncle more. His mother was like a beautiful goddess – something not quite of this earth.

Then there was his half-brother, Richard Grey, another of his close friends, who was Comptroller of his Household. His uncle Lionel was his chaplain although he did not see a great deal of him for he had so many other duties to perform, being the Chancellor of Oxford University as well as Bishop of Salisbury and Dean of Exeter.

How could he be so many things all at once? Edward had asked Anthony, who replied that it was possible; and at the same time to be able to keep an eye on his young nephew.

‘After all,’ said Edward, ‘he is a Woodville.’

Anthony agreed. He had always taught the boy that there was something very special about the Woodvilles. They were capable of doing what ordinary mortals could not. The King, Anthony explained, had recognised that. It was why he had married one of them and so given Edward his incomparable mother; it was why he had put so many of them in the Prince’s household so that his son should have the benefit of their virtues.

Yes, there were many of his mother’s family. Her brothers Edward and Richard were his councillors and even Lord Lyle, his master of horse, was her brother-in-law by her first marriage. His chamberlain, however, was not a Woodville. He was old Sir Thomas Vaughan who had been with him since his babyhood. He seemed to be the only one to hold a post in the household who was not a Woodville.

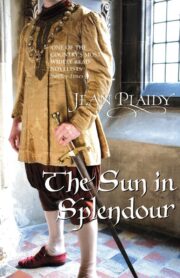

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.