Edward nodded. He was thinking: How can I help her? How can I go against Louis now? I have his pension. Moreover young Elizabeth is to marry the Dauphin. On the other hand it was to his advantage to keep Burgundy and France at each other’s throats. It was this controversy between them which had been of such value to the English when they had been on the point of conquering France, and doubtless would have done so if a simple country maid had not risen to lead the French to the most miraculous victory ever known.

That was long ago. The picture had changed. Edward had no desire to fight in France. He liked things as they were. He had his pension from Louis – what could be better? As long as Louis went on paying that and kept Edward out of debt, Edward was content. Or would be when his daughter was the Dauphine of France.

‘You cannot trust Louis,’ insisted Margaret.

‘One learns to trust no one, alas,’ said Edward with a wry smile. He was wondering how he could refuse his sister without actually saying what he intended to do. He was certainly not going to help Burgundy fight its wars. He was at peace with the King of France and was paid well for it. He was going to let it stay like that. It was not easy to tell Margaret of course. She had come for help, expecting it from him as she had given it to him when he needed it. He would talk round the matter, not saying definitely that he would not help ... but all the time not intending to.

‘So, Edward, what say you?’

‘My dear, it is a matter which I have to discuss with my ministers.’

‘I seem to feel it is you who makes the decisions.’ ‘On a matter like this ...’ He smiled at her ingratiatingly.

‘You see, my dear, the country is at peace. It has known peace for some time. It has come to realise the value of peace ...’

‘So you will not help Burgundy.’

‘My dear, it is a matter I need to brood on. You see, I have an agreement with Louis. My young Elizabeth is betrothed to the Dauphin.’

‘And you think Louis will honour his pledges?’

‘So far ... he has appeared to do so.’

‘I see,’ said Margaret with finality. ‘You are making a mistake, Edward. You will see what happens if you trust the King of France.’

He lifted his shoulders and smiled at her.

She had turned despairing away. She knew her brother. He always wanted to please, which was why he had not given her a firm refusal; but he meant it all the same. He was too fond of the easy life; he liked his pension; he liked his growing trade, his prosperous country. He could have told her all this for he had said No to her request as clearly as if he had stated that he would not help, but being Edward he could not bring himself to say so directly. Yet none could be firmer than he when he had made up his mind and she would not be deceived by his smiles and smooth words.

She saw that her journey had been in vain.

She repeated: ‘You are making a grave mistake to trust Louis.’

He was to remember her words later.

On a dark November day the Queen gave birth to a daughter. She was to be christened Bridget and the ceremony which was to take place in the Chapel at Eltham was as splendid as any that had been performed for her brothers and sisters. Five hundred torches were carried by knights and many of the nobles in the land were in attendance. For instance the Earl of Lincoln carried the salt, Lord Maltravers the basin and the Earl of Northumberland walked with them bearing an unlit taper. Lady Maltravers was beside the Countess of Richmond who carried the baby and on her left breast was pinned one of the most splendid chrysoms ever seen. The Marquess of Dorset, the Queen’s eldest son by her first marriage, helped the Countess of Richmond with the baby; and the child’s two godmothers were the King’s mother, the old Duchess of York, and his eldest daughter Elizabeth.

As the ceremony was performed the torches were lighted and the little Duke of York with his wife Anne Mowbray together with Lord Hastings were all witnesses of the ceremony. After the baby had been carried to the high altar the most costly gifts were presented and when the processions to the Queen’s apartments took place the gifts were carried by the knights and esquires before the young Princess.

There the Queen, a little languid but as brilliantly beautiful as ever, waited with the King to receive those who had taken part in the ceremony.

The baby was taken to her nursery and the company circulated about the Queen and the King. The beauty and good health of the baby were discussed at length and the King sat back watching them all. He was in a somewhat pensive mood on that day. Perhaps it was the birth of another child and the recent death of little George which had made him so. He had a premonition that this might be the last child he and Elizabeth would have. They had eight now – all beautiful, all children of whom he could be proud. His eldest son would be King on his death; his eldest daughter Elizabeth would be Queen of France. He had much on which to congratulate himself.

As in every assembly of this sort there was a goodly sprinkling of Woodvilles. Elizabeth saw to that, and in any case they now held all the key positions in the country. He had been weak about that ... letting Elizabeth rule him. But he had liked the Woodvilles for themselves; they were handsome and charming; they flattered him blatantly of course but he liked flattery. Dorset, his stepson, was a rake who had even dared make advances to Jane Shore, but he enjoyed Dorset’s company. Hastings was there – dear old William, good and faithful friend since the days of their extreme youth. What adventures they had had then, vying with each other, notching up the conquests.

Then a faint feeling of unease came over him. Hastings could never disguise the fact that he deplored the rise of the Woodvilles. Elizabeth hated Hastings. Richard who was not here today disliked the Woodvilles and had never really accepted Elizabeth. He was polite and did all that was expected of him, but beneath the courtesy there was suspicion and distrust. And Elizabeth and her family had not endeared themselves to those of the most noble houses in the country. They were still referred to as upstarts.

For the first time he was thinking of death ... his own death. He wondered what had put such a thought into his head. Was it the birth of a new child; seeing little Richard there with his wife Anne Mowbray – such babies – and thinking of Edward in Ludlow with a household almost entirely made up of Woodvilles? Would Edward be able to step into his shoes? Not yet. There had to be many years before that happened. Young Edward was not as strong as his parents would have wished. There was a deficiency somewhere which affected his bones and he would never be the size of his father. Edward knew how that great height of his had stood him in good stead.

But why think of these things on such a day.

There was Elizabeth looking not so very much older than she had on the day he had first seen her in the forest, though a great deal more regal, of course, more sleek, accustomed to the homage paid to royalty. They could have more children yet. More healthy sons perhaps to follow young Edward and Richard.

Then his eyes fell on the Countess of Richmond. A comely woman, Margaret Beaufort, perhaps a year or so younger than himself. Married now to Sir Henry Stafford but still calling herself the Countess of Richmond – a title she had acquired through her marriage to Edmund Tudor.

The Tudors had always irritated him. They had been good fighters and always the adversaries of the House of York. Naturally, they considered themselves to be the legitimate offspring of Queen Katherine and half-brothers to Henry the Sixth. They might be. It was possible that there had been a marriage between Queen Katherine and Owen Tudor. Then of course Margaret Beaufort herself was the daughter and heiress of John Beaufort, eldest son of John of Gaunt and Catherine Swynford.

He wondered if they had been wise to let Margaret come to Court. She had been quiet and showed no desire to do anything but serve her sovereign. But there was that son of hers, born of her first marriage with Edmund Tudor. He was skulking abroad at the moment and he had his uncle Jasper with him.

Somehow it was not very comforting to think of the Tudors free. Surely they would not have the temerity to consider for a moment that they had any right to the throne! No, that would be absurd. But there was something about them ... a singleness of purpose ... an aura of some sort. It had been there in Owen and had stayed with him until the time of his execution in the market-square of Hereford. He had even made a flamboyant exit. Edward remembered how a woman had washed his face and combed the hair on his poor severed head.

An insidious thought had darted into his mind. Beware of the Tudors.

Then it was gone and a warm feeling of well-being followed.

Life was good. All was going well in England. The King of France dared do nothing but send his annual pension and very soon he would be sending for the King’s eldest daughter to be the bride of the Dauphin and the future Queen of France.

These were appropriate thoughts on such an occasion. On the birth of one daughter he should be thinking of the glorious prospects which were about to be opened to another.

Two peaceful years had passed. The King had grown a little fatter, the pouches were a little more defined under his eyes and his complexion had taken on a slightly deeper hue; his energy was as unflagging as ever. He could still occupy himself with state matters and commerce with an amazing skill and at the same time spend his nights in luxurious debauchery.

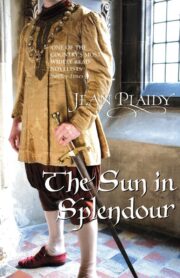

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.