‘I understand,’ she said.

A man was at her side. ‘They are waiting,’ he said. And he led her to the hangman.

It was impossible for Edward not to hear of what had happened to Elizabeth’s one-time serving woman Ankarette Twynhoe.

He did not discuss the matter with Elizabeth although he knew that this was meant to be a blow at her because she had actually recommended Ankarette to the Duchess of Clarence. He did, however, speak to Hastings about it for it was very much on his mind.

‘What do you think of my brother’s latest exploit?’ he asked his friend.

‘He has usurped your powers in arresting that woman and in hanging her immediately after the trial.’

‘And we know the trial was no real one. The jury are saying that they believed the woman innocent and were forced to bring in a verdict of guilty because my brother demanded it.’

‘There will be trouble with Clarence, Edward.’

‘There has always been trouble with Clarence. But this is a flagrant abuse of rights. To kill the woman for no reason but ... but what, William? What motive had he for this foolish and wicked act?’

‘To discredit the Queen and perhaps yourself.’

Edward nodded. ‘How long can it go on?’

‘As long as you allow it.’

‘He is my brother. I have forgiven him again and again, but William, the time has come when I can endure no more. I have begun to think that he would plot against my life.’

‘Only just begun to, my lord? Don’t forget he sided with Warwick and fought against you when he believed there was a chance of displacing you and taking the crown for himself. He would do so again ... given the chance.’

‘And this is the brother I have favoured! I have forgiven him time and time again; and all the time he seeks to stab me in the back.’

‘At least you now realise it.’

‘Always knew it but wouldn’t face it. You know my nature. I want to think well of everyone.’

‘Even when they prove themselves to be your enemy? I know you well, Edward. You doubted me once ... I who have ever been your faithful friend. It would be well now to direct a little more watchfulness towards the Duke of Clarence, for I have a notion, my lord, that we must be careful indeed.’

Edward nodded. Hastings was right.

Clarence rarely came to Court. He wanted to give the impression that since his wife and child had been poisoned on the instigation of the Woodvilles they might well turn their attention to him.

He made a rule of never eating while at Court. He would make such elaborate excuses which said as clearly as though he had uttered the words: ‘I fear that I may be poisoned.’

Edward was losing patience with him; moreover people were talking about the end of Ankarette; the fact that she was so hastily despatched and several members of the jury had declared that they deeply repented having pronounced her guilty, for guilty she was most certainly not and they had given their verdict out of fear of the Duke of Clarence.

Rivers was very watchful of Clarence. Edward could understand that. Who could know what wild plots were even at this time forming in Clarence’s mind? The case of Ankarette Twynhoe was an indication of what great lengths he would go to – however absurd – to point a finger at his enemies. Clarence was a fool, thought Edward, but fools could make a great deal of trouble, and he could never be sure what Clarence was plotting and what turn such plots would take. Of one thing he was sure: Clarence had always wanted the throne and had resented Edward’s being the elder, and whichever way he looked he must see Clarence as a menace.

He should have taken some action over the case of Ankarette, for it was so clear that the woman had been completely innocent and the case against her had been trumped up by Clarence. If he could behave as he had, wreaking vengeance on an innocent woman just to prove that the Queen was really the guilty party, he would be guilty of any folly. Elizabeth said little as was her wont but she had been greatly disturbed over Ankarette’s death and understandably so.

Hastings learned from one of the women with whom he consorted that certain soothsayers and necromancers were drawing up horoscopes of the King and the Prince of Wales, to try to discover how long they had to live. Hastings thought it wise to report this to Edward, because when soothsayers and such like acted so it was usually at the request of someone who was interested in the death of a certain person.

Hastings had traced the horoscopes to a Dr John Stacey of Merton College, Oxford, and he suggested that the King look into the matter and discover why this man was casting these horoscopes and at whose instigation.

A law had been made forbidding that anyone set up horoscopes of any members of the royal family without first asking the King’s permission, and Dr John Stacey was arrested for having done this and he was conducted to the Tower.

The King gave orders that he was to be questioned and if he refused to betray his clients he should be requested to do so with a lack of gentleness. Edward awaited the outcome with a great longing in his heart that nothing should be proved against his brother.

However the rigorous questioning brought forth an interesting piece of information. Stacey had been asked for the horoscopes by a certain Thomas Burdett, and Thomas Burdett happened to be a member of Clarence’s household.

So the King had discovered what he had suspected and hoped not to find. Clarence was eagerly awaiting his death and he knew his brother too well not to guess that if it did not come quickly he would grow so impatient that he would attempt to assist nature.

Edward was in a dilemma. He must show Clarence where this foolish careless plotting was leading him. He had overlooked the Ankarette Twynhoe affair although he knew that he should not have done so. He longed for Clarence to act in a brotherly way towards him, to be like Richard, to help him, not to threaten him as he was constantly doing.

Elizabeth was very uneasy. Edward had come back from France with Louis’s pension and what pleased Elizabeth more than anything, the promise of the Dauphin for her eldest daughter. Making grand marriages for her family had always been her delight, now with the daughter of a King there was no end to her ambitions. She had announced that in future young Elizabeth should be known as Madame le Dauphine. But the death of Ankarette Twynhoe had upset her a great deal. Not only because she had known and liked the woman but because of what it meant. Clarence was her enemy and, because of his rank, a deadly one. He was a fool, she knew, but he was powerful; and men such as he was would always find those to follow him.

Stories came to her ears of rumours that were circulating, and she knew they were set about through Clarence and those who served him. One which disturbed her deeply was the story that Edward was a bastard. He was, according to this particular account, the son of an archer of great height and exceptional good looks who had charmed the Duchess of York during one of the Duke’s many absences. The story was ridiculous, of course. Anyone who had ever known Proud Cis would see how ridiculous it was to accuse her of taking an archer lover; moreover if any member of the family had the Plantagenet looks it was Edward; he was very like Edward Longshanks only considerably more handsome. No, it was a ridiculous story and would be discounted by most people as the jealous fabrication of an ambitious brother who was so eager to get his hands on the crown that he was ready to think up the wildest tales. All the same, it was dangerous, and an indication of the way Clarence was moving.

It was against Elizabeth’s principles to talk of state matters with her husband and her persuasions had always been of the most subtle kind, but she was really frightened now. It occurred to her that if anything happened to Edward, her little son would be in a very dangerous position indeed. Clarence must be removed.

The King noticed her depression and asked what ailed her. She burst out that she was tortured by anxieties. She feared for their children and in particular for the Prince of Wales.

‘It’s Clarence,’ she said. ‘Oh Edward, he is your enemy. You know he is saying you are not your father’s son. That means that you have no right to the throne.’

‘Nobody takes any notice of Clarence’s drivellings.’

‘A jury did and that cost an innocent woman her life.’

Edward was silent, and Elizabeth caught his hand and lifted her fearful eyes to his face.

‘I am frightened for our little Edward. He is so young.’

‘No harm shall come to him. I shall see to that. Nor to any of the children. The country is with me, Elizabeth, as firmly as it ever has been beside any king. Clarence has his followers it is true, but they are nothing compared with those who would support me.’

‘I know ... I know. But he is dangerous, Edward. And I think of the children ... and of you too. I fear for us all.’

Edward was thoughtful. He said: ‘Something must be done. Something shall be done.’

Edward began by sending Dr John Stacey and Thomas Burdett with Thomas Blake, a chaplain at Stacey’s college, for trial. They were found guilty of practising magic arts for sinister purposes, and condemned to be hanged at Tyburn. As was usual in these cases the sentence was to be carried out immediately. However, the Bishop of Norwich interceded for Blake, who he said was involved simply because of his association with Stacey’s college and it had not been proved that he was actually aware of what was taking place.

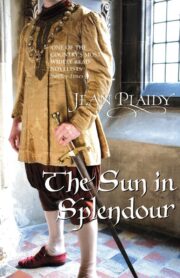

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.