‘Did you know that Hastings has a pension from France of two thousand crowns a year?’

‘Because he is your close friend. Because he is expected to work for France.’

‘As I am, dear brother. Well, there is no harm in that. This will be good for the country. French money coming into it and not a drop of English blood to buy it.’

‘You and your friends have profited indeed,’ said Richard. ‘But the men will be disgruntled. They came back empty-handed.’

‘With their limbs intact. Oh come, Richard, when you are as old as I you will know that diplomacy and sound good reason bring more good than battle cries.’

Richard could not be convinced that the treaty was an honourable one and he was not going to say so.

Edward looked at him steadily and said: ‘A difference of opinion does not change the feelings between two good friends, I hope.’

‘Nothing could challenge my loyalty to you.’

‘So thought I,’ said Edward. ‘I trust you, Richard. You have always been my good friend. I need your friendship particularly as I cannot rely on it from George. He troubles me, Richard.’

‘What is he plotting now?’

‘I do not know what. But I know he plots. I would I could rely on him as I do on you.’

‘You will never be able to.’

‘Nay. But you and I shall stand together, Richard, eh? Never shall we forget that we are brothers ... whatever may befall.’

Richard was comforted to know that the bond between them was as strong as ever, even though they had disappointed each other, even though they could not always act in unison, they could rely on the loyalty – one to the other.

Edward showed that Richard’s attitude had made no difference by bestowing new lands on him and Richard returned to Middleham pleased to be away from the vanities and insincerities of Court. Back with his wife and his son the apprehensions would be blown away by the fresh northern air.

Richard had been right when he had said the men would be disgruntled because they must return without booty. There was grumbling among the soldiers who had thought to come home rich; they would not have minded a scar or two, they said. They had joined the army to fight and what had happened? They had been to France and come back again ... just as they went.

The people who had paid good money for victories were disappointed too. The King had come riding through the country charming the money out of their pockets, asking most graciously for benevolences and what had happened? He had just gone to France and come back again!

Disappointed soldiers roamed the countryside. If they could not loot French villages they would loot English ones. The roads had become unsafe.

Edward’s reaction was immediate. He set up judges all over the country and he himself made a pilgrimage from north to south. Anyone caught robbing, raping or murdering would be hanged at once. There should be no mercy for offenders. He would have law and order throughout the land.

His action was immediately effective and the outbreak of violence died down as suddenly as it had risen.

In the market-squares Edward explained to the people what had happened. He had taken an army to France, yes, and they in their generosity had enabled him to do this with their benevolences. ‘My friends and loyal subjects,’ he said, ‘we have humbled France. What think you would have happened if we had fought great battles ... and even won them. What good would that be to you? You cannot live on glory. Conquest is great and good when there is no other way of achieving the best for a nation. But I have taken my armies to France and the King of France has paid me highly to desist from making war. I did desist. I return your men to you ... your husbands ... your brothers ... they are with you again. I have come back with a full purse and that means that with this money I can strengthen my country. All this good I can bring you with no cost to you, my friends. The King of France is paying your taxes. Was that not worth raising money for? You have won these concessions which I have brought to you through your benevolence, good people. From here we go on ... to greatness.’

They listened. They loved him. How could they help it? He was so handsome. Many said they had never seen a more handsome man. He was clever; he was shrewd; he was the King they wanted. The sun was high over England in all its splendour. The people loved their King.

Chapter VIII

A BUTT OF MALMSEY

Isabel, Duchess of Clarence, was feeling very ill. She dreaded her confinement which was now imminent. She would never forget the first of all which had taken place when she was at sea with her father, mother and sister Anne. Her father had been forced to leave England with his family and although she had been eight months pregnant at the time and in no condition to travel, she had been obliged to go.

The misery of that time, the agony she had suffered only to produce a dead child had remained with her ever since and although she had had two healthy children, Margaret and two years later Edward, she still was fearful.

She wished that Anne or her mother could be with her. But they were at Middleham. The Countess was ageing and Anne she believed did not enjoy robust health.

No, she would try not to worry, try to fight the terrible weakness which overcame her, try to forget the discomforts of her condition and remind herself that they were normal.

She had a very good attendant who had been sent to her by the Queen. The woman was not young and seemed to have a great deal of experience. The Queen had been most affable and Isabel supposed that Edward had suggested she should be for the King was anxious to show that he bore George no malice for those days when he had joined with Isabel’s father and fought against him.

The woman Elizabeth had sent was Ankarette Twynhoe and she had been in the Queen’s service for some time. Isabel welcomed not only the woman but the goodness of the Queen in sending her.

Isabel sighed for peace. Often she remembered the days at Middleham when she and Anne with Richard and George used to ride together and play games and gave no thought to the future. Or perhaps George did. He was always wanting to win in everything, to ride faster, to shoot his arrows further ... it had always been the same with George. He had enjoyed showing his superiority over them all which he could do quite easily, being older and definitely taller and more handsome than Richard. George was boastful, exaggerating his successes, ignoring his failures. He was very different from Richard. People liked George better though. George was always the most handsome person present except in the company of his brother Edward, who outshone everyone. Isabel, who had come to know George very well after being married to him, realised that he hated his brother. Not Richard ... he had nothing to hate in Richard considering himself superior in every way, but Edward. She had seen his eyes change colour when his elder brother’s name was mentioned; she had seen that clenching of his hands, that tensing of his muscles and she had known how the hatred rose within him, because sometimes in the privacy of their apartments he had let it loose in all its fury.

George could never forgive fate for making Edward the elder. But for that George would have been King; and what George wanted more than anything on earth was to be King. It was for that reason that he had sided with Isabel’s father against his brother. Warwick must have promised him that he would be King, but she guessed her wily father would never have allowed that to happen. She herself had been very disconsolate when the feud had arisen between the King and her father. She knew that Warwick was called the Kingmaker and it was no empty title; but it had been his great mistake she was sure to part from Edward.

Poor George! Oddly enough she loved him, and what was perhaps stranger still, he loved her. Her weakness appealed to his strength perhaps, but he had always been tender with her, and she would listen to his grandiose schemes. She encouraged him. She wanted to know what was in his mind. He would talk to her sometimes about the wildest schemes and they were all tinged with his hatred of his brother and the goal in the plans led to that one thing – the crowning of George, no longer Duke of Clarence, but King of England – in the Abbey.

She often wondered what the outcome would be and in the last few days she had doubted whether she would be here to see it.

That was wrong. Women sometimes felt like this when they dreaded a pregnancy. Her cough was worse and she had a pain in her chest. She and Anne had both caught cold easily. In Middleham Castle their mother had coddled them and at the least sign of a cough they were put to bed with hot fomentations on their chests. But her mother was with Anne now and they were in the North and she was here in Gloucestershire which was one of their favourite counties. George liked it, so she did.

She called to Ankarette who came at once.

‘You are feeling unwell, my lady?’

‘It is my chest. I have a pain there. Oh it is nothing. I have had it before ... often.’

‘My lady, I think perhaps you should go to bed. Will you allow me to call your women?’

Isabel nodded. ‘I think perhaps, my lady, you should go into the new infirmary at Tewkesbury Abbey. You would be well attended there.’

‘Yes, I believe these monastic infirmaries are very good.’

‘My gracious lady the Queen has great faith in them, as you know.’

‘Indeed, yes,’ said Isabel. ‘Perhaps I should go.’

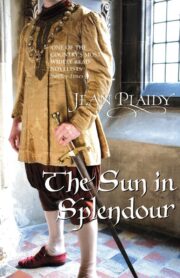

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.