Strangely enough what distressed the Duchess almost as much as Edward’s loss of his throne – though they all insisted that that was temporary – was the defection of Clarence. That one member of the family should proclaim himself the enemy of another, was to her intolerable.

Secretly she made up her mind that she would try to persuade George to stop this nonsense. She had always been rather fond of George – more so than she had of Richard. She knew that Richard was perhaps more worthy, that he was good, studious and devoted to Edward. She knew too that George was too fond of eating, drinking – particularly drinking – and generally indulging himself. He was vain, because he had a certain charm; he was handsome though they all suffered by comparison with Edward; he was clever in a way, sharp, crafty rather than brilliant. But how could one explain one’s likes and dislikes? George had always been a favourite of hers.

He must be made to realise the dishonour of turning to Warwick against his own brother.

Edward was astounded by the splendour of the Court at Bruges. He had always known that Burgundy was not only the most powerful man in France but the richest, but this far surpassed his own Courts at Westminster and Windsor and he had been considered somewhat extravagant in his love of tasteful decorations and furniture.

But this was no time for such comparisons. His great aim was to get help which would enable him to sail back to England, to rout out Warwick and when he had done so ... What? The idea of beheading Warwick could arouse no enthusiasm in him. There was so much he could remember of Warwick. How he had adored him in the old days! And to think it had come to this was so distressing. One of the worst aspects of being driven out of his kingdom was the fact that Warwick had done it.

Although Margaret was passionately devoted to her brother’s cause, her husband was reluctant to support Edward outwardly.

‘Louis is waiting for a chance to attack me,’ he said, ‘and if he and the Lancastrians joined up against me ... I should be in a difficult position. Louis is treating Margaret and her son as very honoured guests ... friends even. I have to go carefully.’

He was willing to help Edward in secret but he would not come out in the open and do so. This was frustrating, for the acknowledged support of the Duke would have gone a long way.

However, Edward was optimistic. Each week brought new help. The merchants had always been aware of Edward’s superior qualities as a ruler and were ready to support him and money came to him from the Hanseatic towns. As the months passed he could see the day coming nearer when it would be possible for him to land with an army which could win him a victory over his enemies.

During those months he became very interested in an Englishman who had taken service in the Burgundian Court under the patronage of his sister. This was a certain William Caxton who had begun his career as a mercer to a rich merchant called Large who had been Lord Mayor of London. Caxton had gone to Bruges on the death of the Mayor and became associated with the merchant adventurers. He became a successful businessman and did much to promote trade between England and the Low Countries. But as he grew older – he must have been about fifty years of age when Edward arrived at his sister’s Court – he became interested in literature, and when Margaret suggested he join her Court and continue his writing, Caxton gladly accepted the invitation.

Edward talked to him of the merchant adventurers with whom he had had some dealing but he was more interested in his literary work, particularly a book which he was translating called Le Recueil des Histoires de Troye.

They discussed together the interest of such a work to many people and how unfortunate it was that so few could read it as there was only one copy and it took so long to make another.

Caxton had heard of a process which had been invented in Cologne and which was called a printing-press. He had seen this and had been most interested in it. Edward listened and agreed that it would be a very good thing to have and he wondered whether it would be possible to bring it to England. Caxton was sure it would be and when he had finished his translation he intended to go again to Cologne and then possibly set up a press in Bruges.

‘I will remember that,’ Edward told him, ‘and I hope that when we are in a happier state in England you will visit the Court there.’

Caxton said that it would be an honour to do so, for although he had lived long abroad and had been made most welcome in the Duchess’s Court he did often long for his native land.

The weeks passed quickly and during them Edward worked indefatigably building up arms and men in preparation for crossing the Channel. By March he had accumulated a force of some twelve thousand men and with Richard of Gloucester and Earl Rivers he set sail from Flushing. The weather was against him and it was ten days before he reached Cromer. Some of his men landed to test the state of opinion in that area and discovered that it was solidly in Warwick’s control; he sailed on northwards and finally landed at Ravenspur.

It was not as easy as he had thought for what the people dreaded more than anything was civil war. They had favoured Edward but Edward had been driven out of the country. True, they knew Henry was weak, but Warwick was behind him and Warwick had that aura of greatness which they respected.

But as Edward came to York he found there were plenty to rally to his banner and he began the march south. He was near Banbury when he heard that Clarence was not far off and shortly afterwards Clarence sent a messenger on in advance to tell Edward that he wanted to speak with him.

Edward was pleased for there was a conciliatory note in the message and he believed that his brother was fast regretting his action in turning against him.

Edward was thoughtful. Could it really be that George was looking for a reconciliation? It was too good to be true. If it were so he would forgive him with all his heart. Not that he would ever trust him again. When he came to think of it he had never really trusted Clarence. But if he and his brother were friends again, if Clarence brought his men to fight for him, this would be a tremendous blow to Warwick.

Yes, certainly he would welcome Clarence. Let them meet without delay.

Outwardly it was an affectionate meeting. Clarence looked at Edward shamefacedly and would have knelt, but Edward laid a hand on his arm and said: ‘George, so you want us to be friends again?’

‘I have been most unhappy,’ said Clarence. ‘It was all so unnatural. I was under the influence of Warwick and I want to escape from that influence now.’

‘We have both been under the influence of that man – you so far as to go against your own brother and marry his daughter.’

‘I regret all I have done ... except my marriage to Isabel. She is a good creature and I love her dearly.’

Edward nodded, thinking: She is a great heiress and you also love her lands and money dearly.

Clarence went on: ‘I no longer wish to stand with Warwick. I want to be back where I belong. Our sister Margaret has written to me most affectingly. I have suffered much.’

‘I too suffered from your desertion,’ Edward reminded him.

‘And can you forgive me?’

‘Yes,’ said Edward.

‘By God, together we will fight this traitor Warwick. We’ll have his head where they put our father’s.’

‘It was not Warwick who put our father’s head on the walls of York and stuck a paper crown on it, George. That was our enemies ... our mutual enemies. But yes, we are going to defeat Warwick.’

‘I will bring him to you in chains.’

‘Your father-in-law, your one-time friend! I want him to be treated with respect if we have the good fortune to capture him. I can never forget how he taught me, how he showed me how to fight and win a crown. Sometimes I think I am more hurt that he should take his friendship from me than my crown. I would always treat him with honour. He had his reasons you know for doing what he did. Warwick would always have his reasons. He is my enemy now but he is one I honour.’

Clarence thought what a fool his brother was. But there was a hard side to Edward, he knew; he could be ruthless but where his affections were concerned he was soft. He had married Elizabeth Woodville; he was ready to forgive the man who had taken his crown from him and his own brother who had deceived him. No wonder he had lost his throne! He would lose it again and if Henry were driven out there was one who would stand in to take it: George, Duke of Clarence.

Well, there was reconciliation between the brothers and as Edward had predicted Clarence’s desertion of Warwick and return to Edward had the desired effect. Edward marched without hindrance into London.

Warwick was in Coventry when he heard of Clarence’s defection. There was even more bitterness to come for Louis had signed a truce with the Duke of Burgundy and so was making terms with Warwick’s enemy. Clarence he despised. He had never trusted him but his greatest hope had lain with the French King. Margaret of Anjou had left France and with the Prince of Wales and Anne and Warwick’s Countess was about to land in England. He, Warwick, was heading for some climax. Meanwhile Edward had reached London. His spirits rose as he saw the grey stone walls of the Tower and he assured himself that Elizabeth was not far away.

First he went to St Paul’s to give thanks for his return. Then he must see Henry who was at the Bishop of London’s palace close by. Warwick had ordered that he should be taken there and put in the charge of Archbishop Neville and that Neville should let him ride through the streets in an attempt to arouse people’s enthusiasm for him.

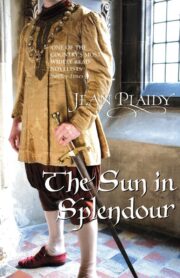

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.