There was good news of Henry the King who had been captured in the North. He had been in hiding for some time, living in fear of capture, resting at times in monasteries so Edward had heard. A life which Henry must have found most suitable. Warwick had met him when he was brought to London by his captors and so that all should realise the depth to which he had sunk they had bound his legs under his horse with leather thongs while he was conducted to the Tower. There he was handed to his keeper.

Edward rejoiced, not only that Henry was his captive but because Warwick’s actions showed that he was still the same strong and firm supporter of the Yorkist King.

They would all be relieved, of course, if Henry died, but they must not hurry him to death or he would become a martyr. Henry was perfect martyr material with all that piety. In the North some of them believed he was actually a saint. Moreover if he were to die there was still his son.

‘Let matters rest as they are,’ Warwick had said, and he added, looking steadily at Edward: ‘They have a way of working out for what is right.’

Warwick’s mind was busy. He had stepped back into his role of chief adviser; he had made a pretence of accepting the Queen. But in truth he hated the Queen. Not because in marrying her Edward had humiliated him in a manner such a proud nobleman would never accept, but he could see that the Woodville family would become more and more important with every passing year. The leading family was the Nevilles –made so by him. And why should it not be so? Who had put the King on the throne? Should not the Kingmaker gather a little for his own family?

And if they were going to be ousted by the upstart Woodvilles this could not be tolerated.

Elizabeth and that diabolical mother of hers were putting their heads together and enriching and empowering their family by the old well tried method – which was the best in any case – of marrying into the greatest families. And they were doing very well.

Anthony was already married to the daughter of Lord Scales and had that title. Anne Woodville had become Lady Essex having married the Earl; Catherine had married the Duke of Buckingham; Mary was the wife of the Earl of Pembroke; Eleanor was married to Lord Grey of Ruthin, Earl of Kent, and the youngest, Martha, was the wife of Sir John Bromley.

Warwick seethed with rage when he thought of Elizabeth’s efforts so far. Those were the Queen’s sisters, already exerting a Woodville influence in the greatest and most powerful families in the country.

This is something I will not tolerate, he thought. It is a decided threat to the Nevilles. We are the leading family. I have upheld and made the King. I will not be supplanted by these upstarts. Not only will they ruin the country, but they will ruin me.

Moreover the Queen had brothers.

Elizabeth was at this time considering her brothers. She was delighted with her sisters’ marriages. Her mother was right. That meeting under the great oak had been inspired. From that all their blessings had begun to flow.

She was at this time concerned about her brother John who was now nineteen years old. She wanted the best possible for him. The girls had all married well but the boys were even more important.

When Jacquetta made the suggestion to her Elizabeth could scarcely believe it for the suggested bride was the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk. True she was one of the richest women in the country, but she was almost eighty. Jacquetta, however, was serious.

When Elizabeth broached the subject to Edward he burst into laughter. He thought it was a joke. But Elizabeth was not given to joking on sacred matters.

‘I really mean it,’ she said. ‘John will take care of the old Duchess’s estates.’

‘Oh he’ll take good care of them, I doubt not,’ said Edward.

‘Edward, my brother should be married. Please grant me this. I want it to be.’

He put his hands on her shoulders and kissed the heavy lids. He had still not discovered what this extraordinary power she had over him really meant. Perhaps he loved her; it was strange, for he had played at love so many times, but again that might be why he was bewildered by the real thing when he encountered it. In any case he was fiercely glad that he had married her. And if she wanted the old lady of Norfolk for her brother, she should have her.

Everyone thought it was a joke at first. How could it be otherwise – a boy of nineteen and a woman of nearly eighty. The Duchess was distressed but too old and tired to care very much. She doubted the handsome young man would bother her. In any case it was a royal command, and the Duchess had no alternative but to submit.

It was the joke of the day. People talked of it in the shops and the streets.

Some said it was a marriage of the devil. Such an old woman ... such a young man. It was done for the money, the estates, the title. This was often the case but surely never quite so blatantly before.

Jacquetta was beside herself with glee.

‘You know how to manage the King,’ she said to her daughter. ‘Be careful not to lose your place in his affections. Be lenient with his misdemeanours, never criticise or reproach. Accept everything and he will deny you nothing.’

So the marriage of young John Woodville and the ancient Duchess was celebrated.

Warwick said: ‘This is the last insult. I cannot accept this woman and her overbearing family. They are making the throne a laughing-stock. I made a King. I can unmake one.’

The King was in a contented mood when Thomas Fitzgerald, Earl of Desmond returned from Ireland to report on events there.

He liked Desmond. A handsome man of immense charm. As an Irishman he was a good man to govern there. Warwick had chosen him and was pleased with him. Desmond and Warwick were on the best of terms.

A few years earlier when George Duke of Clarence had been made Lord Lieutenant of Ireland – a title for the King’s brother because Clarence was neither of an age nor ability to be able to conduct the affairs of that troublesome island – Desmond had been made Deputy, which meant that, in the circumstances, he was in full command.

Warwick had seen him on his return to England and had confided in him his horror and disgust at the King’s marriage.

‘Not only is this low-born woman on the throne but she is now so enriching her family that we are going to find ourselves governed by Woodvilles if we do not take some action.’

‘What action?’ asked Desmond with a certain alarm.

‘Some action,’ said Warwick mysteriously. ‘Edward is not so firm on the throne as he would appear to think. Do not forget that Henry, the anointed King, languishes in the Tower and across the water is a very bold and ambitious Queen with a son whom she calls the Prince of Wales and reckons to be true heir to the throne. Would you not think that a King who reigns in such circumstances should not be careless ... particularly in his dealings with those who have put him there?’

‘He should rid himself of the lady and her tiresome relations.’

‘So think I,’ said Warwick. ‘And when I consider the humiliation I was forced to suffer to put a crown on that woman’s head, it maddens me so much that I would do myself some harm if I gave way to my anger.’

‘I can understand your feelings,’ said Desmond. ‘I know that while the King was married he allowed you to negotiate with France.’

‘That is the truth,’ said Warwick. ‘The country cannot afford any more of these disastrous marriages. At the moment they are amused by this diabolical match between John Woodville and the old Duchess of Norfolk. But in truth it is no laughing matter.’

Desmond was grieved to see Warwick in such a mood; and what seemed to him most disturbing was that there was a rift between him and the King.

Desmond was devoted to Warwick whom he admired more than any living man; he was well aware of the part the Earl had played in affairs, but at the same time he was fond of the King. This was a very distressing state of affairs and he feared trouble might lie ahead.

When he presented himself to Edward the King was most affable. They discussed affairs in Ireland and Edward congratulated Desmond on what he had done.

‘You must get in some hunting while you are home,’ he said. ‘How was the game in Ireland?’

It was very good, he was assured. But Desmond would greatly enjoy hunting with the King.

When they were riding through the forest, they found themselves apart from the rest of the company. Edward was affable and disarming. He was so friendly that Desmond quite forgot as people often did that he was the King.

Edward mentioned Warwick and asked how Desmond had found him.

‘As ever,’ replied Desmond. ‘Full of vitality ... as clever as he ever was.’

‘I have a notion that he does not like the Queen.’

This was dangerous ground and Desmond should have been prepared for it.

He was silent. He could not say that Warwick had not mentioned this to him for Warwick had made his feelings very clear. He hesitated. Then the King said: ‘And what do you think of the Queen, Desmond?’

‘I think she is remarkably beautiful.’

‘Well, all must think that. What else?’

‘She is clearly virtuous. It is amazing that she who was a widow with two children should look so ... virginal.’

The King laughed.

‘I think I have been wise in my marriage. Do you, Desmond?’

It was difficult to answer. To give the reply the King wanted would have been so false and Desmond was sure that that would have been obvious.

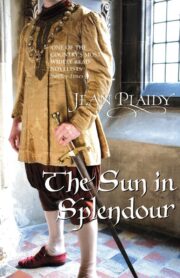

"The Sun in Splendour" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sun in Splendour". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sun in Splendour" друзьям в соцсетях.