Sitting up in bed sipping wine, Alienor watched the baby snuffle in his sleep and smiled with triumph. Now let Louis eat his words that she was a useless bearer of girls. How right this marriage must be that God had shown his approval and she had borne Henry a son on the first try. She only wished he were here to share this moment with her, but he would know soon enough, and even without him, the savouring was sweet indeed.

Henry eyed the white stallion recently purchased by his groom. The horse was intended for parade and ceremony rather than everyday riding. Being so full of energy, Henry was always hard on his mounts and wore them out swiftly, but this one was to be coddled for occasional use.

‘Lame,’ he said, his nostrils flaring with temper. ‘I have paid five pounds of silver for a lame horse that has only been a waste of stable space thus far. How is that a good purchase?’

The groom flushed. ‘It was not lame when I bought it, sire.’

‘Hah, it wouldn’t be, but you were duped all the same.’ Henry walked around the horse again, looking at its trembling flank and the white of its eye. ‘No good for breeding either. Nothing but dogsmeat. Get it out of my sight.’ He dismissed both horse and groom with angry impatience. He expected good service in all parts of his life as a matter of course, and when it did not live up to expectations, it made him angry.

He had been in England since the winter and during that time had undertaken two serious campaigns, both of which had ended in stalemate because the barons on either side would not commit to a pitched battle. Everyone was weary of war; everyone wanted peace and, even through the skirmishing and posturing, negotiations were going forth. It all took time and effort, and Henry was having to school himself to a patience he was far from feeling, and it exacerbated his irritation when he could not trust his groom to do a small thing such as selecting a sound palfrey.

Henry retired inside the keep at Wallingford to read the day’s messages and give further orders. A scout had arrived to report that Stephen was in Norfolk, striving to bring the troublemaker and renegade baron Hugh Bigod to heel. Henry had no intention of pursuing him there. Indeed, in some ways it was all to the good that he was chasing Bigod. Henry found the baron useful as an ally, but it did not mean he trusted or liked him. The man had proven himself a cunning, self-serving bastard.

He paused to ruminate and his gaze crossed the chamber to rest casually on Aelburgh and little Geoffrey. He watched her play with the child who was just beginning to walk and he smiled a little at the infant’s determination. It was good to have a domestic presence even at the heart of a battle camp – something to offer comfort but not important enough to require attention until he chose to give it.

As he reached to take a cup of wine from an attendant, another messenger was ushered into his presence in haste by Hamelin, his expression bright with suppressed excitement. ‘Tell the Duke what you have just told me,’ he commanded.

‘Sire.’ The man knelt to Henry. ‘Eustace, Count of Boulogne, is dead.’

Henry put his cup down and stared at the man and then at Hamelin. ‘What?’

‘Sire, he choked on his food while claiming hospitality at the abbey of Bury St Edmunds. Men are saying it was the wrath of the saint coming down on him because he had raided the monastery lands. He is being borne to Faversham for burial.’

Henry leaned back in his chair and absorbed the news. This must be God’s intention – His way of making everything right by clearing a way that had been blocked. Eustace had been the boulder in the path to peace and now he was suddenly gone. In Stephen’s camp, and with Stephen himself, everything would be unravelling thread by thread. Even those who had stayed with him would be looking for a new allegiance and now there could only be one. He possessed all the youth and vigour Stephen lacked. All he had to do was continue undermining the older man’s plinth until he toppled him. And now Stephen’s eldest son was dead, that plinth was precarious indeed. Suddenly the matter of the lame white horse became a trivial thing. ‘God rest his soul, and God bless Saint Edmund,’ Henry said with a serious face and levity in his eyes.

‘Stephen has other sons,’ Hamelin said. ‘There’s still William.’

‘But he will not stand in the way as Eustace has done,’ Henry replied. ‘He is malleable, for which everyone will be thanking Christ. I doubt he will stand in our way. Even if he does …’ He let a shrug speak for the rest.

A week later another messenger arrived in Henry’s camp on a lathered horse, this time from Aquitaine with the news that Alienor had been safely delivered of a fine, healthy baby boy, christened William, the name they had agreed before Henry left for England.

If Henry’s cup had been full before, now it ran over. He had known she would bear a boy, but the proof in the letter confirmed that God was smiling upon him, especially when he realised his son had been born on the same day, perhaps taking his first breath at the very moment that Eustace was choking to death. If that was not God’s will in the matter, he did not know what was.

Louis broke the seal on the letter that had arrived from Henry, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou. He did it slowly, glancing round at the courtiers in the chamber as a matter of course to see who was watching him. He was feeling sour and unwell today. His physician said there was too much melancholy within him and had bled him to balance his humours, but that had only given him a sore arm and a headache. The news of Eustace of Boulogne’s death had done nothing to improve his dark mood. It meant that another obstacle had been removed from Henry FitzEmpress’s path to the English throne. It also meant his sister Constance was now a widow and he would have to go about extracting her dower from Stephen and finding her another husband.

Slowly he unfurled the scroll and, with a feeling of mild dyspepsia, read the customary flourishes of salutation. Then he came to the place where Henry was pleased to inform his overlord that God had seen fit to bestow the joy and blessing of a strong, healthy son on him and the Duchess of Aquitaine. The words burned themselves into Louis’s brain while he sat and stared at them. How could such a thing be? Why had God not favoured him instead of that Angevin upstart? What had he done to make God turn His face against him in such a way?

‘Bad news?’ asked his brother Robert, raising his brows and holding out his hand for the letter.

Louis drew back and, rolling it up, tucked it inside his sleeve. Everyone would know soon enough, but it was a wound he wanted to keep to himself for as long as possible. ‘I shall tell you later,’ he said. ‘It little concerns you.’

Robert gave him a look askance.

‘It is between me and God,’ Louis said, and left the room. He wished the messenger had foundered on his way to Paris and fallen into a bog so that he did not have to carry this letter, this knowledge against his breast.

Arriving at his chamber, he dismissed everyone and lay down on his bed. He was filled with grief for the son he did not have – for the son that Alienor had miscarried long ago when she was his young, fresh bride. For the fact she had borne the heir that should have been his to Henry of Anjou, while giving him only daughters. Feeling desolate, abandoned, and full of self-pity, he covered his head with a pillow and wept, wishing he had never been drawn from the cloister to become a king.

50

Angers, March 1154

‘Madam, the Duke your husband is here,’ announced Alienor’s chamberlain.

Alienor stared at him in dismay. ‘What, already?’

He looked wry. ‘Yes, madam.’

‘But he was not due until … Ah, never mind. Delay him as long as you can.’

He gave her a dubious look but bowed out.

‘Oh, that man!’ Alienor cried, torn between infuriation and joy. His heralds had arrived this morning, announcing he would be here towards nightfall, but the daylight was still strong and there were several hours until sunset. ‘I do not see him for more than a year, and then he springs himself upon me and I am not prepared.’

‘It will not take a moment to finish,’ Marchisa said, practical and optimistic as always. ‘Your lord may notice you, but he will not care if your hair is plaited in six braids or two.’

‘But I will care,’ Alienor complained, but only because she was annoyed. In truth it did not really matter. ‘Make haste then,’ she said. ‘They will not be able to hold him back for long.’

Her women coiled her hair in a gold net and tightened the laces on her tawny silk gown to emphasise her once-more trim figure. The nurse busied herself with baby William who at seven months old was a vigorous bundle, no longer bound in swaddling, but clad in an embroidered white smock. The nurse put a bonnet on his head, and Alienor told her to draw out a quiff of his hair so that the glittery red-gold colour was plain to see.

Not entirely satisfied, but knowing it would have to do, Alienor hurried to the hall and settled herself on the ducal chair on the dais with the baby in her lap. Emma and Marchisa arranged her skirts in a graceful swirl and Alienor drew a deep breath.

Moments later she heard Henry’s voice protesting that no, he did not need to change his clothes, and no, he did not want to don his coronet, take refreshment, comb his hair, or anything else anyone might concoct to delay him. He flung open the door and stalked into the room, his cloak flying like a banner and his stride hard and fast. His complexion was flushed and there was a grey glitter in his eyes that verged on anger. Then he stopped abruptly and stared at Alienor, his chest heaving.

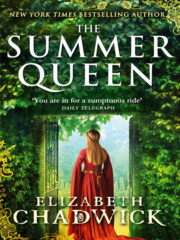

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.