Saldebreuil shook his head. ‘I do not know, madam.’

‘I will tell you,’ Hamelin said grimly. ‘They were led by my half-brother Geoffrey. We are less than a day’s ride from Chinon, which is his by the terms of our father’s will. Henry knew he would try something like this.’

Alienor’s mouth twisted. ‘Younger sons may see me as fair game for their ambition,’ she said with contempt, ‘but I put a far greater value on myself than a stepping stone to raise their place in the world. It is a vile disgrace that I cannot ride in safety to and from business with my overlord.’

These attempted abductions made her realise that she could not remain unwed. Every time she ventured forth from one of her strongholds, determined suitors would be lying in wait to seize her and bring her before a priest. In truth she had no choice.

44

Poitiers, April 1152

Alienor gripped the sealed packet in her hand, knowing this was her last moment to change her mind. Waiting for the messenger to come to her, she stood by the window, looking out on the beautiful spring day. Everything was in leaf and bud and glorious blossom. It was a few days past the anniversary of her father’s death and he had been in her thoughts. Geoffrey de Rancon too, although his grave had been made in bleak autumn. All that remained were poignant memories, and she must face reality, not live on dreams. Truly it was time to make a new beginning – and what could be better than wedding a young man in the April time of his life?

Her chamberlain announced the messenger and, with a sigh, she turned from the window. The man, whose name was Sancho, doffed his cap and knelt to her. She had selected him to bear this message because he was reliable, discreet and intelligent. The letter itself was worded in such a way that if he was apprehended, the news he carried would not be obvious to the casual reader, although Henry would understand. After a final hesitation, she bade him stand, and gave him the packet.

‘Deliver this to Henry, Count of Anjou, and make sure he and no other receives it,’ she said.

‘Madam.’ Sancho bowed his head.

‘And give him this.’ She handed him a soft suede hawking gauntlet. ‘Tell him I hope he will find it useful in the future. Here is silver for your expenses during your journey. Ride swiftly, but do not take risks. Go now.’

From her window she watched him leave, swinging into the saddle of a fiery bay courser, its hooves already in motion. He would change horses along the way and only stop to sleep when he had to. Depending on Henry’s whereabouts, she estimated he should receive the letter within ten days at most, which meant she had a little less than three weeks to prepare her wedding feast.

Henry was at Lisieux overseeing preparations to invade England. The sound of axes chipping wood and the pungent scent of hot pine pitch filled the spring morning. Ships, soldiers and supplies were all being stockpiled ready for a full summer campaign across the Narrow Sea.

Henry had been just two years old when his grandfather King Henry I had died and Stephen of Blois had stolen the throne. He was nineteen now, Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou, and ready to remedy the situation. He knew his supporters in England were desperate after seventeen exhausting years of unrest, but he also knew Stephen was ageing and his barons were looking to the future. Several had already made cautious approaches to Henry, eyeing him up as a potential leader instead of Stephen’s son Eustace, who was unpopular. Henry was prepared to do everything in his power to bring these men over to his side.

He looked up from a tally listing the latest arrival of horses to see his chamberlain approaching with a messenger in his wake. The latter’s face was weather-burned and wore lines of exhaustion, but there was a gleam in his eyes.

‘Sire,’ he said in the accent of Poitou, and bent his knee. ‘My mistress the Duchess of Aquitaine bids you greeting.’

‘And you are?’ Henry demanded. It was always useful to fix faces and names in one’s mind.

‘Sancho of Poitiers, sire.’

Henry gestured him to stand. ‘Well, Sancho, I assume you are here to bring me more than just your mistress’s greeting?’

The man produced a letter and a hawking gauntlet from his battered satchel. ‘Sire, the Duchess bade me say that if you care to visit her at Whitsuntide, she will be pleased to take you hunting and discuss matters of mutual interest.’

Henry gave the messenger a sharp glance before lowering his gaze to the seal attached to the document by a plaited silk cord. The imprinted wax bore the image of a slender woman in a dress with hanging sleeves. A falcon perched on her left wrist and she held a lily in her right hand.

Henry read what she had written and then raised his head to glance around the bustle of the camp. This would put an anchor on his immediate plans, but he had to act on the contents in Alienor’s letter. He might not have an emotional investment in a match with her, but this was about dynasty and power. He felt a glimmer of satisfaction as he reread the message. He had been almost certain she would ask him, but he had still harboured a shred of doubt because women were fickle. Hamelin had told him about Geoffrey’s stupid and pathetic attempt to abduct her on the way to Poitiers. He intended to put his younger brother in his place the moment he had dealt with more pressing matters.

There was no need to cease his preparations to invade England. He could go and marry Alienor while his officers continued to work. Thoughtfully he donned the hawking gauntlet and stretched and clenched his fist inside it. The smell of new leather tingled in his nose, rich and slightly metallic, and for some reason it made him feel hungry, as if he had not eaten in a week.

He sent across the camp for Hamelin and, when his brother arrived from supervising the testing of a new siege machine, told him to make ready to ride to Poitiers. ‘I am going to be a bridegroom and I need a second to stand with me,’ he said.

Hamelin folded his arms. ‘What about England?’

‘Having the wealth of Aquitaine to support us is all to the good. England will benefit greatly.’

‘Louis won’t be pleased,’ Hamelin said.

Henry waved his hand as if swatting a fly. ‘I can deal with Louis; I have his measure, but he does not have mine.’

‘In law you should ask his permission as your overlord,’ Hamelin persisted.

‘You are jesting!’ Henry punched his half-brother on the arm with his gauntleted fist. ‘Presented as a fait accompli, Louis will give it, but I would have to be out of my mind to make such a request beforehand. To seize the moment, you must be ahead of it.’ He cast his gaze to the position of the sun. ‘It’s too late to ride today, but we can make ready to move at first light – and travel hard.’

That evening in his chamber, Henry checked over the small baggage pack he intended taking to Poitiers. He needed to ride fast and light, but had made room for fitting clothes for his wedding and a gift for his bride. He looked at the two jewelled cuff clasps shining in their leather case. Set with sapphires, emeralds and rock crystals, they were part of the German treasure belonging to his mother. She had given them as funds for his campaign, but he judged they would do better service as a gift to his bride.

Aelburgh entered the room, her thick ash-blond hair tied back from her face in a red silk ribbon. She was cradling a small baby in her arms. She sat down on a stool, unfastened her dress and chemise, and put the infant to nurse.

Henry eyed her full white breast and rosy-brown nipple before the baby covered the areola and began to suckle vigorously.

‘The child is a drunkard,’ he said with amusement and a pang of tenderness, for this was his firstborn son and proof that his seed was sufficiently strong to beget healthy male children. The baby, christened Geoffrey, had been born seven weeks ago. The Church said a man should not have intercourse with a woman when she was feeding an infant but Henry had little time for such pernickety rules, considering them the work of stifled priests, not God, and he had brought Aelburgh and the baby with him on campaign for comfort and company.

Aelburgh smiled. She had beautiful white teeth and full lips. ‘He is greedy like all men,’ she said and, looking down, she gently stroked the baby’s fine sandy-gold hair.

Henry laughed. ‘I am feeling rather greedy now, I admit,’ he said, ‘but for a different kind of sustenance.’

As soon as Aelburgh had finished feeding the child and put him in his cradle, Henry took her to the bed and buried his face in her wonderful hair. The energetic bout of lovemaking and the pleasure of his climax dimmed his energy and soothed him for a moment and he was content to lie beside her, his arms folded behind his head. She laid her hand on his stomach and lightly tugged on the fuzzy stripe of hair running from his navel to his groin.

‘I have to leave you for a while,’ he said. ‘But keep the bed warm for me.’

She lifted her head. ‘I thought I was coming with you?’

‘Sweetheart, I am not talking about England. I have business in Poitiers first. I will visit you and the child when I can, but it may not be for a while. Do not worry, you will be well provided for in my absence.’

‘But I thought …’ She sat up and looked at him, her grey eyes wide.

Henry said wryly, ‘I am getting married, my love – to the former Queen of France and Duchess of Aquitaine. When a lady of such rank and wealth sends you a proposal, you do not turn it down.’

Twin notes of caution and dismay entered her voice. ‘Married?’

Henry grimaced. He did not understand the pets of woman over such matters and it made him impatient. ‘I have told you I will look after you. Don’t worry.’

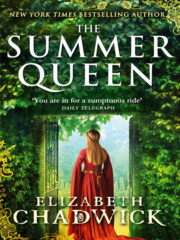

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.