The chamberlain and squires arrived with Alienor close behind. For an instant Petronella became a wild thing, redoubling her efforts to get at Raoul, but then suddenly, as if she had taken a mortal blow, the fight went out of her and she flopped like a slaughtered doe.

‘Bring her to my chamber,’ Alienor said brusquely. ‘Marchisa will tend to her.’

Raoul hefted her in his arms and followed Alienor, with the squires leading the way by torchlight up the winding stairs to Alienor’s rooms. Alienor directed him to place Petronella on her bed, and Marchisa hastened to her side.

‘She tried to kill me,’ Raoul said with a mingling of pity and revulsion. ‘She was waiting for me with a knife.’

Alienor sent him a contemptuous look. ‘You were with one of the courtesans, were you not?’

Raoul spread his hands. ‘What if I was? My union with Petronella has long been impossible. I dare not lie with her because I fear for my life – that she might have a blade under the pillow and stab me to the heart. She constantly accuses me of bedding other women even when I have been chaste.’ His lip curled. ‘I decided I might as well hang for a sheep as a lamb.’

‘You knew she was volatile from the first.’

He puffed out his cheeks. ‘I thought she was a lively handful, but, God’s eyes, not this.’

‘You also knew she was the sister of the Queen and thought her worth the risk. You plucked the fruit and enjoyed the taste, and now you say it is poisonous.’

‘Because it is! There is no reasoning with her.’ He made a wide gesture with his arm. ‘All that remains are these black moods and despair. She no longer knows what is imagined and what is real.’

‘I will deal with her. Just leave; I cannot bear your presence here.’

‘If I were you, I would make sure she does not have access to any kind of weapon.’

Alienor closed her eyes. ‘Just go, Raoul.’

‘I will pray for her, but it is finished.’ He left the chamber, his step heavy and his shoulders hunched.

Felice was waiting for him in his chamber, wrapped in his fur-lined cloak and nothing else, but he dismissed her. That appetite had become as cold as yesterday’s pottage.

Kneeling at the small prayer table in the corner of his chamber, he lit a candle and bowed his head. When he rose from his prayers, his knees were so stiff they felt as if they had turned to stone and the unscarred side of his face was slippery with tears.

Biting her lip, Alienor looked at Petronella, who had turned her face to the wall and closed her eyes.

Marchisa said softly, ‘I can do nothing for her. She is in God’s hands, madam.’

‘She is exposed to too much upheaval at court; yet if she retires to Raoul’s estates, she only broods and grows worse. I have been wondering whether to send her to my aunt Agnes at Saintes. She might not find comfort in a nunnery, but she would be supervised and better protected.’

‘Madam, I believe a routine of structure and prayer would help her greatly,’ Marchisa agreed.

Alienor sighed. ‘Then I shall consult with Raoul and write to my aunt and see if she will give her sanctuary. We used to go there often when we were children.’ Her expression grew sad as she remembered running with Petronella in the sun-filled cloisters when their father had visited Saintes. The giggles and laughter, weaving in and out between the pillars, stretching to tag each other, their dresses hoisted to their knees and their braids flying, blond and brown, adorned with coloured ribbons. And then in the church, kneeling to pray but still sending mischievous glances to each other. Perhaps at Saintes, God would remove this darkness from Petronella’s soul and cast out her demons.

‘Oh Petra,’ she said softly, and stroked her sister’s tangled cloud of hair with a loving, troubled hand.

Standing in the palace gardens, Alienor watched the children at play in the golden September morning. They were an assortment of ages, ranging from toddlers only just finding their feet to long-limbed youngsters on the verge of puberty. Among them were Petronella’s three, Isabelle, Raoul and little Alienor. Being without their mother would demand an adjustment but since of late Petronella had been unable to care for them, the parting was going to be less intense. They had been told their mother was unwell and was being taken to the convent at Saintes for rest and healing.

Busy with a piece of sewing, a golden-haired little girl sat beside her nurse. Fair wisps had escaped her braid and made a sunlit halo round her head. She was intent on her task, her soft lower lip caught between her teeth. Another woman held the hand of a toddler with the same blond hair, helping her to balance as she took determined but unsteady steps across the turf.

Alienor remained where she was, feeling marginalised, a part of the tableau yet removed from it like a border on a manuscript. She had bidden farewell to her daughters last night, feeling nothing beyond a regretful sadness as she kissed their cool, rose-petal cheeks. She did not know these children of her womb. The intimacy had been in their carrying, not their lives after the parting of the cord. In all likelihood she would never see them again.

Alienor filled her gaze with a final look at her children, fixing the scene in her mind because it was all she would have for the rest of her life, and then turned away to join the entourage preparing to leave Paris and take the road to Poitou.

On the third day of their journey, Alienor and Louis spent the night at the castle of Beaugency, 90 miles from Paris and 110 from Poitiers. Sitting side by side in formal state for the meal provided by its lord, Eudes de Sully, they presented a united front as King and Queen of France, yet a vast chasm yawned between them, and it was not a calm space. They were desperate to be rid of each other, yet still tied by the process of the law. Louis considered it Alienor’s fault that God had penalised them by denying them a son: she was responsible but he was paying the price. He chewed his food in dour silence and responded to comments in curt syllables.

Alienor was silent too as she concentrated on enduring the moment. Each day brought her closer to freedom from this travesty of a marriage, yet annulment would bring its own crowd of dilemmas. Raising her cup to drink, she noticed a messenger working his way up the hall towards the dais, and immediately she was concerned because only very important news would disturb a meal in this way. The messenger doffed his cap, knelt and held out a sealed parchment, which the usher took and handed to Louis.

‘From Anjou,’ Louis said, breaking the letter open. As he read the lines, his expression grew sombre. ‘Geoffrey le Bel is dead,’ he said. Handing the note to Alienor, he started to quiz the messenger.

Alienor read the parchment. It had been dictated by Henry and, although courteous, gave the barest details. The messenger was relaying the meat of the story: that Geoffrey had been taken ill on his way home after bathing in the Loire, and was to be buried in the cathedral at Le Mans.

‘I cannot believe it.’ Alienor shook her head. ‘I know he was not altogether well in Paris, but I did not think he was sick unto death.’ She felt a welling of deep sorrow, and tears filled her eyes. She and Geoffrey had been rivals, but allies at the same time. She had enjoyed matching wits with him and had basked in the glow of his admiration. Flirting with him had been one of her pleasures and he had been so beautiful to look upon. ‘The world will be less rich for his passing,’ she said, wiping her eyes. ‘God rest his soul.’

Louis dismissed the messenger and murmured the obligatory platitudes, but there was a glint in his eye. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘we shall have to see about the new young Count of Anjou, and whether the boy has the mettle to cope with his responsibilities. I thought him an ordinary youth when he came to court with his sire.’

Alienor said nothing, partly because she was struggling to absorb the shocking news, and partly because this changed everything. She was also wondering how ordinary a youth Henry actually was.

‘It can only be good for France to have an inexperienced youngster to deal with.’

‘He loved his father dearly,’ Alienor said. ‘That much was clear when they came to Paris. He must be sorely grieving.’

‘As well he should.’ Louis turned away to talk to his nobles. Alienor made her excuses and retired to her allotted chamber. Calling for writing materials, she sat down to pen a letter to Henry, telling him how sorry she was and that she would pray for his father. She commended Henry’s fortitude and hoped to express her condolences to him in person on a future occasion. The tone of the letter was courteous and conveyed nothing that could be misconstrued as inappropriate, even by the likes of Thierry de Galeran, whom she had no doubt would read her correspondence if he got the chance. She sealed the letter and bade her chamberlain give it to the messenger from Anjou. Pouring herself a cup of wine, she sat down before the hearth and gazed into the red embers, thinking that if she did marry Henry, she would be facing Louis squarely across a political chessboard, and would need every iota of skill and good fortune to survive.

Alienor entered Poitiers riding a palfrey with a coat dappled like pale ring mail. La Reina perched on her gauntleted wrist, white feathers gleaming. The sky was as blue as an illumination and the sun, despite encroaching autumn, was strong enough to be hot. Alienor felt a wonderful sense of freedom, of coming home, as her vassals flocked to greet her. At first there was no sign of Geoffrey de Rancon, but she could see several Taillebourg and Gençay barons among the gathering. And then she glimpsed him in the throng, recognising immediately the dark wavy hair and tall, straight posture. He turned and her rising heart sank again as she saw it wasn’t Geoffrey at all, but a much younger man – a youth almost.

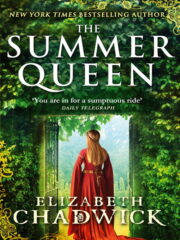

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.