Raoul called the hound to heel and peered under the table. ‘What are you doing, child?’

‘Finding the dice, sire,’ she lisped, and held them out on the palm of her hand.

‘Ah, you weren’t spying on us then?’ Raoul said with a twitch of his lips. His words elicited an uncomfortable silence from the adults.

‘What’s spying, sire?’

‘Listening to what other people say without them knowing you are listening, and then reporting what you have heard to others. If you’re lucky, they’ll pay you for the information.’

She continued to stare at him. ‘That’s telling tales.’

Raoul’s shoulders shook with suppressed laughter. ‘I suppose it is. Just remember that all knowledge is profit.’ He smiled briefly at Alienor and, rising from his stoop, went to join the dice game and show the children one of his tricks. Louis shook his head and snorted with amusement. ‘Fool,’ he said.

‘A knowing fool though.’ She watched him bend over the table and perform a vanishing trick with the newly retrieved dice. Marie leaned against his leg like a kitten after milk and he patted her head.

Alienor looked down at her lap. She knew she had to tell him. That smile from Raoul had been a warning. ‘Louis,’ she said. ‘I am with child. You are to be a father once more.’

His expression went very still and then, like raindrops hitting a pool, the emotion twitched across his face. ‘Truly?’ he said. ‘You speak truly?’

Alienor nodded and set her jaw. She wanted to cry, but not with joy. ‘Yes, I speak truly,’ she said.

Louis took her hands in his and leaned forward to kiss her brow. ‘That is the greatest news you could give me! The Pope was right and wise. This is indeed a new start. I am going to protect you and look after you and make sure you have the best possible care.’ His chest expanded. ‘Tomorrow I shall send for the most learned physicians in the land. You and our child will want for nothing. I shall do everything in my power to keep you and the child safe.’

Alienor tried to smile but could not for she knew that now her incarceration would begin. Already she felt as if she could not breathe.

If the winter had been long and hard, then the early summer of 1150 was hot enough to blister the paint from the shutters and warp doors, creating fissures and cracks in the gasping wood. Even in the top chamber of the Great Tower, with the shutters open and the insulation of the thick, cool stone, the air was warm and stale. Labouring to bear her child, Alienor’s only relief from the heat came as successive layers of sweat dried on her body.

The midwives had told her all was well and progressing as it should be, but the hours still slipped by in the pain and endurance of Eve’s lot. She could not help but remember the stillbirth on the road from Antioch and it churned up all her terror, rage and grief from that time. Those emotions had never gone away, and rode her hard as she sought to push this new child from the womb and be free of the burden.

There came the last moments of struggle, the final effort and the baby was born, pink and wet and living, with a set of lungs that filled the still air in the room like a fanfare. But all the attendants and adults in the room were silent and the anticipation on their faces turned to blank expressions and sidelong glances.

Petronella leaned over the bed and held Alienor’s hand. ‘It’s another girl,’ she said. ‘You have another beautiful daughter.’

The words meant nothing to Alienor. It was as if her mind was cut off from her feelings just as the cord severed her from the new baby. She had had no choice in Tusculum but to share Louis’s bed and this child was a matter between the Pope and her husband. She had only been the vessel. That it was a girl did nothing to pierce her numbness. There was naught she could do about it and so it had to be accepted. She turned her head towards the window, to the faint breath of breeze.

‘Perhaps the next one will be a boy,’ Petronella said. ‘Our mother had two daughters and a son, and so do I.’

Alienor looked at her sister. ‘It doesn’t matter,’ she said. ‘What God decides, He decides.’

Petronella gently stroked Alienor’s loose hair. Then she rose and stood aside for the midwives to deal with the afterbirth as the contractions gathered again. ‘Perhaps it is for the best,’ she whispered. ‘You can be free now.’

Louis had been pacing and waiting for news ever since hearing that Alienor’s labour had begun. As always such things seemed to take forever. This time he knew it would be a son. The Pope had given his word, and the child had been conceived in the papal palace. Everyone he consulted assured him that the child was a boy. He had made sure Alienor had had the best of care and protection throughout the pregnancy. He was to be named Philippe, and Louis was ready to take him to his christening before the altar of Saint Peter in the royal chapel the moment he was brought from the birthing chamber. He had even written some documents in his son’s name, promising gifts to abbeys, penning the words himself without the use of a scribe so that he could form the inky nib around the name ‘Philippe’ and feel that wonderful sense of destiny.

Abbé Suger sat with him. They had been at prayer together earlier and were now busy with matters of government. Suger had aged in the bitter winter last year, becoming gaunt and wizened, his words punctuated by a persistent dry cough. However, despite his physical frailty, he was still politically active and astute as they discussed their troublesome neighbours.

‘It would be better to negotiate an agreement with Geoffrey of Anjou and his son, rather than going to war against them, sire,’ Suger said. ‘The Angevin support was vital to me during the time that I was regent during your long absence.’

‘You are saying I should ignore their impertinence?’ Louis drew himself up. ‘They must be taught their place.’

‘Your brother attacked the Angevins when you were still on your pilgrimage. Geoffrey of Anjou is a powerful vassal. You have recognised him as Duke of Normandy and now he has conferred that title on his son. Better for now to have them in our camp.’

‘Geoffrey of Anjou conferred that title without my sanction, and the young man is a whelp who needs bringing to heel,’ Louis snapped. ‘I shall not let upstarts dictate to me.’

‘Indeed, sire. But you should think of the future. Many favour the Angevin’s heir to sit on England’s throne rather than Stephen’s son.’

Louis’s nostrils flared. ‘I will not see an Angevin wear a crown. They have already seized more than their due.’

Suger persisted with firm but weary patience. ‘But you should leave your pathways open,’ he said. ‘And you should not keep risking yourself in war until you have your own heirs firmly established. The country is still recovering from the harsh winter and spring. The crops are barely in the fields. Make this a time of husbandry and rest.’

Louis looked at his tutor, really looked, and noticed the shadows under his eyes and the hollows in his cheekbones. Suger had been elderly for a long time, but Louis had never thought of him as being frail or mortal. Certainly he had wished him gone or less interfering on many an occasion, but now, suddenly, he saw that what had been a constant in his life, taken for granted, was on the wane. This time of husbandry and rest might also be one of letting go for Suger. ‘I shall think about it,’ he said, and managed to keep his voice steady, even though the moment of realisation had jolted him.

‘That is all I ask of you for now, and I hope your wisdom sees you through.’ Suger gave Louis a shrewd look. ‘And you do have wisdom, my son, even if it is hard-earned and sometimes overridden by your own stubborn will and the foolish advice of others.’

Not so frail that he was unable to lecture. Louis’s moment of concern passed into the background.

A steward rapped on the door with his rod, and announced that attendants from the Queen’s apartments had arrived with news of the birth.

Louis’s chest swelled as he commanded their admittance. Now he would see his son.

The midwife came to him, a bundle carried in her arms. Her eyes were downcast and her expression was neutral. ‘Sire,’ she said and, kneeling to him, spread the blanket open in her lap to show him the naked baby. Louis gazed down at the tiny creature as it wriggled in the sudden exposure to cold air and gave a mewling cry. He was being shown a girl baby, but that was impossible and the sight rendered him speechless. He looked from the baby to the gathering of courtiers accompanying the midwife and back to the baby in utter disbelief. It was true, but it couldn’t be. He set his jaw. ‘I have seen enough,’ he said with a flick of his hand. ‘Take the child away.’

The midwife carefully folded the infant back in the blanket and, with her escort in tow, bore it from the room. Louis looked down at his hands, which were shaking. His mind was blank with shock; he couldn’t think. It was as if the missing genitalia on the child had caused that part of himself to vanish too, and he felt as if all of his body was crumbling inwards.

‘Be steady,’ Suger said. ‘At least the Queen has proved she is fertile.’

Louis paced the room numbly, touching this and that. He paused by his earlier working and the word ‘Philippe’ stood out to him like a brand. ‘I had a son a moment ago,’ he said. ‘Now he is gone, usurped by a girl, and I have nothing.’ He seized the vellum and crumpled it in his fist.

‘Sire …’

He cast Suger a look filled with anguish and fury. ‘What will people think of me that I cannot sire a son on this woman even with the blessing of the Pope upon us? What will people say?’ He could feel a terrible pressure of tears growing behind his eyes and there was pain in his stomach. ‘It is all her fault. She has let me down again. If God cannot persuade her to produce a boy, then surely I cannot.’ He felt a moment of almost overwhelming bitter hatred against his wife for doing this to him, and then the shock surged again. He had been so certain it would be a boy. He had been convinced by the Church that he was doing the right thing. The Pope had promised. They had forced him into this and made him a victim. ‘No,’ he said to Suger, holding up his hand. ‘Do not try to console me and tell me all will be well. I should have had this marriage annulled long since.’

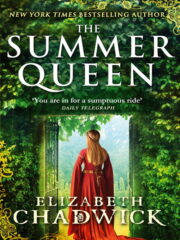

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.