‘You disobeyed my orders and men whose names you are not fit to utter have died today because of your incompetence and cowardice.’

‘I will give my life if you ask it, nephew,’ de Maurienne volunteered.

Louis’s gaze stabbed the kneeling men. ‘I am inclined to accept your offer,’ he snarled. ‘Neither of you is worth a pot of piss! You are both under arrest, and I will deal with you as you deserve in the morning. Prepare your souls. My household guard sacrificed themselves for me and their bodies are lying out on that mountainside, stripped and butchered by infidels.’ His voice cracked with rage and grief. ‘Their blood is on your hands for eternity, do you hear me? For eternity!’ He raised his dirty, bloodstained fists to emphasise the point, and then slowly lowered them. ‘Bring me maps,’ he commanded. ‘Find me de Galeran – if he survived.’ He pointed to de Maurienne’s tent. ‘I will take this for my own. See to it.’

Geoffrey and de Maurienne were dragged away through a crowd clamouring to see them hanged here and now, especially Geoffrey. Men spat at them and struck out as they passed amid cries of ‘Shame!’ and ‘Treason!’ Alienor’s heart began to pound. Sweeping her cloak around her, she hastened to the tent that Louis had just commandeered and forced her way past the soldiers guarding the entrance. ‘Husband,’ she said to Louis, invoking the familiar form as she dropped the flaps.

He was standing in the middle of the tent, his face in his hands and his body shuddering with sobs. He made an abrupt turn to her and raised his head, tears streaming down his grimed cheeks. ‘What do you want?’ he said raggedly.

She lifted her chin. There was no falling into each other’s arms. No ‘Glad you are alive.’ They were far beyond that. ‘I am sorry for the good men we have lost, but you cannot hang your uncle and my seneschal on the morrow, and you must make sure your men do not do so tonight.’

‘Are you trying to rule me again?’ He bared his teeth. ‘Do not dictate to me what I can and cannot do.’

‘I am telling you that if you do this thing, you will have a war between our troops that will finish what the Turks began.’ She drew herself up. ‘Geoffrey de Rancon is my vassal and it is my prerogative to chastise him for what he has or has not done. You shall not hang him.’

‘They disobeyed my orders,’ Louis snarled, ‘and because they did not do as they were told, my men – my friends – were slaughtered. I shall do as I see fit.’

‘They did what they thought best. They made a mistake, but it was folly, not treason. You have no right to hang Geoffrey, because he is my vassal. If you do, then the Aquitaine contingent will rise in revolt against you. Do you really want to contend with that? And if you hang Geoffrey, you will also have to hang your uncle – your own mother’s brother – because they share the blame. Are you willing to do that, Louis? Will you watch them both swing? How will that sit with your men?’

‘You know nothing!’ he sobbed at her. ‘If you had been there, seeing your friends cut to pieces in front of your eyes, you would not be so swift to leap to their defence! My bodyguards gave their lives to protect mine, while de Maurienne and de Rancon were warming their backsides at the fire and taking their ease. This is all their fault, all of it. If you were any kind of wife to me, you would be supporting me in this, not casting obstacles in my way.’

‘You have a penchant for always seeing reason as an obstacle. If you hang these men, you will lose two battle commanders and all of their vassals who will no longer cleave to your banner, and that means you will only have yourself to blame when what remains disintegrates in your hands.’

‘Be silent!’ He raised his clenched, bloody fist.

Alienor did not flinch. ‘If you do this, you doom yourself,’ she said, her voice quiet but hard. She turned her back on him and left the tent.

Behind her she heard a crash as if something had been kicked over. A real man would not succumb to a boy’s tantrum, she thought, and the sound only served to increase her contempt for him and her fear of what he might do.

Alienor went with Saldebreuil to the tent where Geoffrey and Amadée de Maurienne were being held under house arrest. A crowd of knights and serjeants, survivors of the rearguard, had gathered outside and were shouting insults, most of them directed at Geoffrey. ‘Poitevan coward!’ and ‘Southern softsword!’ were the least of them. Chanted threats to hang the men surged and receded, and more soldiers were drifting towards the tent and joining the crowd with each moment. ‘Find Everard des Barres. Quickly!’ Alienor commanded Saldebreuil.

He snapped swift orders to one of his men, and then with a handful of household knights made a corridor for Alienor to approach the tent entrance. ‘Make way for the Queen!’ he bellowed.

Soldiers fell back, but Alienor was aware of their muttering and resentment. A real sense of danger tingled down her spine. At the tent entrance she paused, drew a deep breath, and then parted the flaps.

Geoffrey and de Maurienne sat at a trestle table with a flagon between them and a platter on which stood a loaf of hard bread and a rind of cheese. They looked up with taut faces as she entered; both then rose and knelt to her.

Alienor knew she dared not betray her emotions by a single look or gesture. ‘I have spoken to the King,’ she said. ‘He is furious, but I believe when it comes to the crux, he will spare you both.’

‘Then we must believe in your belief, madam,’ said de Maurienne, ‘and my nephew’s good sense. But what of them?’ He nodded towards the tent flaps. Something struck the side of the canvas with a heavy thud. A stone, she thought, and the volume of the shouting increased.

‘Help is at hand,’ she replied, praying that it was, and hoping Louis would indeed see sense by the morning.

‘Well, if it is French help, they are likely to string us up,’ Geoffrey said grimly, ‘and if you have summoned our men, there will be bloody fighting in the camp between the factions.’

‘Credit me with more sense than that,’ she snapped. ‘I have sent for the Templars.’

A look of relief passed between the men, but then Geoffrey shook his head. ‘Perhaps we do deserve to die,’ he said.

‘You have already committed enough folly to last you into your dotage, without adding more,’ she said, covering her fear with anger. ‘When we reach Antioch, my lord, I am sending you back to Aquitaine.’ He inhaled to protest and she raised her hand to silence him. ‘My mind is made up. It will benefit me and Aquitaine far more than if you remain here.’

Geoffrey stared at her, his eyes glittering with tears. ‘You will shame me before all.’

‘No, you fool, I will save your life, even if you seem keen to throw it away. Listen to them.’ She gestured to the tent flaps. ‘They will make a scapegoat of you. Someone will put a knife in you before this journey is done. It is different for my lord de Maurienne. He is the King’s uncle, and they will say he followed your lead. They may not hang you today, but nevertheless they will find some way of murdering you. I will not let that happen to … to one of my senior vassals. Besides, I need your strong arm to prepare Aquitaine for when I return. So much will have changed.’ She raised her brows in emphasis.

‘Madam, I beg you …’ Geoffrey looked at her with his heart in his eyes; then he swiftly dropped his gaze and bowed his head. ‘Do not send me away.’

Alienor swallowed. ‘I must. I have no choice.’

There was a taut silence; then Geoffrey said, ‘If that is your wish, I must yield you my obedience, but I do it at your will, not my own.’

De Maurienne had been silently watchful throughout the exchange, and Alienor wondered how much they had given away. ‘The Queen speaks wisely,’ the older man said. ‘I can weather the storm, but you are vulnerable; you have enemies. It is best for all that you leave.’

Outside the tent, the shouting and insults had fallen silent, replaced by the sound of a heavy tread in unison and the clink of weapons. Alienor turned to the entrance. A row of Templar knights and serjeants was lining up facing the crowd, shields presented, hands on sword hilts.

‘Madam.’ Their commander, Everard des Barres, gave her a stiff bow.

Alienor returned the courtesy. ‘Sire, I ask you to guard these men. I fear for their lives. There will be more bloodshed among us should anything happen to them tonight before the King has made his decision. We have problems enough in the camp without adding to them.’

Des Barres gave her a shrewd look from narrow dark eyes. He and Alienor had never been particularly cordial with each other, but were both pragmatic enough to deal on political and diplomatic terms. ‘Madam, you have my personal oath that these men will not be harmed.’

There would be a price to pay at some point, she knew, but des Barres was a man of his word. The Templars had no affinity apart from God, and were the best soldiers in Christendom. ‘Thank you. I leave this in your capable hands, my lord.’

Alienor left the tent without looking back because she did not want to meet Geoffrey’s gaze. The Queen’s traditional role was that of peacemaker; let it rest at that and pretend that her heart was not breaking.

Having passed a worried, sleepless night, Alienor had just finished her morning ablutions when Louis arrived. In the morning light, his face was pale and ravaged, with eyes red-rimmed from exhaustion and weeping. ‘I have decided to spare my uncle and de Rancon,’ he said. ‘It will be a far greater punishment for them to live with their shame.’

‘Thank you,’ Alienor said, her tone conciliatory and subdued. She felt weak with relief, for he could so easily have chosen execution and in the end she could not have stopped him. ‘Geoffrey must return to Aquitaine.’

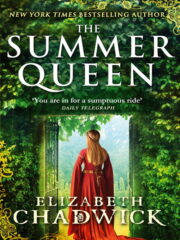

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.