‘Good Christ,’ cursed Saldebreuil. ‘Where in God’s name are de Rancon and de Maurienne?’

Alienor shuddered. She had a terrible vision of Geoffrey’s arrow-quilled body sprawled across the rocky path. What if the vanguard had been hit and destroyed? Surely she would have heard the noise of battle and their horns summoning help. Where were they?

Pilgrims screamed and ran, were caught and cut down. Serikos lunged and tried to rear. She staggered against his surging shoulder. Turkish fighters hurled out from the rocks, brandishing scimitars and small round shields. Saldebreuil and another knight engaged them, their larger kite shields protecting their bodies. Alienor heard the grunts of effort, saw the chop of swords and the crimson spurt of blood as Saldebreuil dealt with the first Turk and then took down another. She grabbed Serikos’s reins and struggled into the saddle. ‘Ride for higher ground!’ she cried to her ladies. ‘Ride for the clouds!’

Gisela screamed. Alienor whipped round to see the grey staggering, an arrow deep in its shoulder. ‘Climb up behind me,’ Alienor commanded. ‘Ride pillion!’

Weeping in terror, Gisela set her foot on Alienor’s and hauled herself on to Serikos’s rump. Alienor struck her heels into the gelding’s flanks and urged him upwards. The higher they climbed the better their chances: safer than trying to turn back through a net of Turkish swords.

Below, Alienor heard the vicious clash of weapons and the screams of people and horses as the slaughter continued. She felt the first stirrings of panic. Behind her, Marchisa and Mamile were praying to God to spare them, and she added her own entreaties to theirs, her voice tight in her throat.

They came upon a loose palfrey, its reins dangling dangerously near its forelegs, its dead young rider sprawled across a boulder. Alienor’s blood froze as she recognised Amadée de Maurienne’s squire. Dear God, dear God. She stared round wide-eyed but there was no sign of the rest of the vanguard, just this sole corpse. Swallowing, she turned back to the matter in hand. ‘Take the horse,’ she urged.

Gisela shook her head, staring at the blood-drenched hide. ‘I can’t, I can’t!’

‘You must! Serikos cannot bear us both! Quickly now!’ Alienor caught the palfrey’s reins.

Making small sounds of distress, Gisela slid from Serikos’s back. A Turk leaped out at her from behind a rock, his scimitar drawn, and Gisela’s whimpers turned to screams. The Saracen prepared to strike, but never completed the move because Saldebreuil arrived at a gallop and cut him down with a swipe of his sword. He had two more knights of Alienor’s escort with him, and a serjeant. Swiftly he dismounted, bundled Gisela on to the dead man’s horse and swung back into the saddle. ‘God knows where the vanguard is,’ he snarled. ‘We’re being slaughtered!’ He spurred his blowing, bleeding horse and smacked Serikos with the flat of his gory blade.

The journey down the other side of the mountain was terrifying. The horses scrambled and slipped on the precipitous, uneven ground and Alienor feared they were going to take a tumble and shatter their bodies on the bones of the mountain. The cloud was thick here and boulders and scree loomed out at them without warning. She was certain that at any moment they were going to ride off the edge of the world and vanish into oblivion. She kept expecting to come upon more arrow-shot and butchered corpses from the vanguard, but there was nothing. Perhaps they had indeed taken that leap into the void.

The ground became softer and flatter, the boulders and humps diminishing to scree. At their backs, stones pelted and bounced down the mountainside, disturbed by their passage, and the horses skidded. Saldebreuil led them at a rapid trot along a track where piles of fresh horse droppings showed that the path had recently been used. Eventually they came to an open area in the valley with a swift-running stream. Soldiers had pitched tents and the horses had been put to graze. Twirls of smoke rose from fresh campfires, and the scene was so pastoral and calm that Alienor had to fight disbelief. Only when the guards on picket duty saw the riders approaching at a fast gait did they stand to attention.

‘The middle is under attack!’ Saldebreuil bellowed at them. ‘Get back there, you craven fools! We’re being massacred and robbed. The Queen is safe by the grace of God, but who knows what will happen to the King!’

A soldier ran to fetch Amadée de Maurienne and Geoffrey de Rancon, while the knights scrambled to resaddle their horses.

‘Why didn’t you wait?’ Saldebreuil snarled at Geoffrey as the latter arrived at a run, buckling on his sword. ‘The Turks are slaughtering us on the mountain and we’re caught like lambs in a pen! It’s your fault, but all of us from Aquitaine will carry the blame!’

Geoffrey’s olive complexion was yellow. Without a word he turned and began shouting orders. De Maurienne was already astride his stallion and rallying the men.

‘Guard the camp,’ de Maurienne bellowed to Geoffrey. ‘Prepare for attack. I will deal with this.’ He spurred back the way he had come at a hard gallop.

Geoffrey clenched his fists, his chest heaving. Alienor was furious with him, but was not about to upbraid him in the midst of a desperate situation, and above all else she was limp with relief that he was alive. ‘Do as de Maurienne says, and be swift about it,’ she said curtly. Without waiting for aid she dismounted from Serikos.

‘I swear I did not know. I thought to make a camp out of the weather as a refuge.’ His voice almost cracked. ‘If I had thought for one minute that the Turks would attack, I would never have ridden ahead. I would never risk your life.’

‘But you did.’ Her body shook with reaction. ‘Your decision carries a high price. If you have a tent prepared, as you say, have your squire escort us there.’

‘Madam …’

She set her jaw and turned away before she either struck him or fell upon him in weeping dissolution.

Geoffrey’s squire escorted Alienor and her ladies to a tent in the middle of the camp. A pot of hot stew bubbled softly over a brazier. Sheepskins had been placed on the floor and covered several benches arranged round the coals. Marchisa, practical as ever, prepared a hot herbal tisane, and pressed one of the fleeces around Gisela’s shoulders, for the young woman’s teeth were chattering.

Alienor could hear Geoffrey bellowing orders and men running to obey. She tried to compose herself, but inside still felt as if she was tearing down that slope of rocks and scree towards a shattering impact. Thank God Geoffrey was alive. Thank God they had not betrayed each other. But his error would have terrible repercussions, both in the wider field and the personal. She felt sick. She drank the tisane, and left the tent to do what she could for the survivors who were straggling into camp, dazed, bleeding and disorientated.

Night fell and the trickle into the camp continued from the decimated pilgrim middle sector, and then men from the rearguard in a disorganised scatter. No one had seen the King. Some said they had seen him riding to the aid of the embattled middle with his bodyguard, but not since then.

Robert of Dreux arrived, his shield almost in pieces and his horse cut about the haunches and lame. Amadée de Maurienne was with him, looking shaken and old. ‘We could not find the King,’ he said in a trembling voice, ‘and the Turks and the natives were all over the mountain, looting and butchering.’

Alienor absorbed the news with an initial surge of shock, but as the jolt left her, she shook her head. Louis was not the world’s best commander, but when it came to fighting ability in a crisis, and sheer luck, he had few equals.

‘God preserve him. God preserve us all.’ Robert crossed himself. He was quivering and his eyes were wide and dark. If Louis did not return, then Robert, here and now, would become King of France. The air was huge with tension. She knew how ambitious Robert was, and already she could see the glances being cast his way, each man wondering if he should dare to be the first to kneel and give his allegiance.

If Louis was dead, then she was no longer Queen of France. Robert’s wife Hawise would bear that burden instead. She could return to Aquitaine, with her daughter, and this time marry as she chose. The notion was like a prison door opening, but she dared not allow herself to think it might be true, and pulled back from the thought as if she had touched a hot iron bar.

Throughout the evening, stragglers continued to arrive. The guards were tense, challenging each one, afraid that the Turks would creep up under cover of darkness and encircle the camp. The cloud on this side of the mountain was sparse, and the stars shone like chips of rock crystal in the bitter night.

Alienor was crouching beside a wounded knight, offering him words of comfort, when she heard the shout go up. ‘The King, the King is found! Praise God, praise God!’ She rose to her feet, clutching her cloak around her, eyes wide. She had been hoping and fearing. She had expected him to succeed and survive, but her thoughts, although controlled, were on a knife edge. She hurried towards the shouting and then stopped abruptly because Louis, filthy, bedraggled and blood-spattered, was swaying where he stood, legs wide-planted for balance, and on their knees before him, heads bowed, were Geoffrey de Rancon and Amadée de Maurienne.

‘Where were you?’ Louis was demanding. ‘You are to blame. You rode off to see to your own comfort. You hid like cowards and left me and my men to die. De Warenne, de Breteuil, de Bullas: hacked to death before my eyes. This is betrayal that amounts to treason!’

‘Sire, we did not know,’ pleaded de Maurienne. ‘We thought it was safe. If we had known, we would not have come down to make camp.’

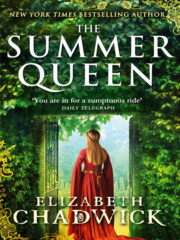

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.