‘Nevertheless, we should think about it,’ Alienor persisted. ‘We are Duke and Duchess as well as King and Queen, and our stay was curtailed because we had to return to Paris. We must not let my people think we have forgotten them.’

He avoided her eyes. ‘I will ask Suger and see what he says.’

‘Why should it be up to Suger? He has a duty to advise you, but he treats you as if you are still his pupil, not the King of France. You can do as you please.’

Louis said defensively, ‘I do take his advice, but I make my own decisions.’ He reached for his clothes and began putting them on.

‘You could decide to go to Poitou after the coronation. It would not be too difficult, surely?’ She tossed her head, making her hair shimmer over her naked body like cloth of gold.

Louis devoured her with a glance and his pale complexion flushed. ‘No,’ he conceded. ‘I suppose it would not be too difficult.’

‘Thank you, husband.’ She gave him a demure, sweet smile. ‘I so much want to see Poitiers again.’ The image of the good and doting wife, she knelt at his feet to fasten his shoes.

‘I do love you,’ Louis said, as if blurting out a shameful confession, before tearing himself away and hurrying from the room.

Alienor gazed after him and gnawed her lower lip. Obtaining what she wanted was a constant battle, and had become more of a routine irritation than an interesting challenge.

Her women arrived to dress her. She chose a new gown of russet and gold damask with deep hanging sleeves and coiled her abundant hair into a net of gold thread set with tiny gemstone beads. Floreta held up a delicate ivory mirror for Alienor to study her reflection. What she saw pleased her, for while her beauty did not rule her life, it gave her an advantage she was prepared to exploit. Her face needed no enhancement, but she had Floreta add a subtle touch of alkanet to redden her lips and cheeks in defiance of her mother-in-law’s scrubbed severity.

Her chamberlain announced that a set of painted coffers she had ordered had arrived, together with some new bed curtains, and a pair of enamelled candlesticks. Alienor’s mood brightened further. She was gradually making her chamber into a little part of Aquitaine in the heart of Paris. Northern France was not without its great riches, but it did not possess the sun-drenched ambience of her homeland. The French palace was heavy with the weight of centuries, but no more so than Poitiers or Bordeaux. However, Adelaide’s dull and sombre tastes permeated everything, so that even this great tower, built by Louis’s father, had the feel of a building much older and stultified with time.

Servants arrived with the new furnishings and Alienor began arranging them. She had one of the chests set at the foot of the bed and the other, depicting a group of dancers hand in hand, put against the wall. She had the existing bed hangings taken down and new ones of golden damask put up. The maids opened out a quilt of detailed whitework stitched with eagle motifs.

‘More purchases, daughter?’ Adelaide said from the doorway, her voice full of icy disapproval. ‘There is nothing wrong with what you had before.’

‘But they were not my choice, madam,’ Alienor replied. ‘I want to be reminded of Aquitaine.’

‘You are not in Aquitaine now, you are in Paris, and you are the wife of the King of France.’

Alienor replied with a hint of defiance, ‘I am still Duchess of Aquitaine, my mother.’

Adelaide narrowed her eyes and stalked further into the room. She cast a disparaging look over the new chests and hangings. Her glance fell on the rumpled bed that the chamber ladies had yet to make, and her nostrils flared at the smell of recent congress. ‘Where is my son?’

‘He has gone to see Abbé Suger,’ Alienor replied. ‘Would you care for some wine, my mother?’

‘No, I would not,’ Adelaide snapped. ‘There are more important things in the world than drinking wine and frittering money on gaudy furnishings. If you have time for this, then you have too much free rein.’

The air bristled with Adelaide’s hostility and Alienor’s resentment. ‘Then what would you have me do, madam?’ Alienor asked.

‘I would have you comport yourself with decorum. The sleeves on that dress are scandalous – almost touching the ground! And that veil and headdress do nothing to hide your hair!’ Adelaide warmed to her theme, flinging out her arm in an angry gesture. ‘I would have your servants learn to speak the French of the north and not persist in this outlandish dialect that none of us can understand. You and your sister chatter away like a couple of finches.’

‘Caged finches,’ said Alienor. ‘It is our native tongue, and we speak the French of the north in public company. How can I be Duchess of Aquitaine if I do not maintain the traditions of my homeland?’

‘And how can you be Queen of France and a fitting consort for my son when you behave like a silly, frivolous girl? What kind of example are you setting to others?’

Alienor set her jaw. It was pointless arguing with this cantankerous harridan. These days, Louis was far more likely to listen to the ‘silly, frivolous girl’ than his carping mother, but the constant criticism and sniping still wore her down and made her want to cry. ‘I am sorry you are vexed, Mother, but I am entitled to furnish my own chamber as I choose, and my people may talk as they desire, providing they are courteous to others.’

Adelaide’s abrupt departure left a brief but awkward silence. Alienor broke it by clapping her hands and calling brightly to her servants in the lenga romana of Bordeaux. If she was a finch, she intended to sing her heart out in defiance of everyone and everything.

Two days later, accompanied by her ladies, Alienor went to walk in the gardens. She loved this green and fragrant part of the castle complex with its abundance of plants, flowers and lush turf. Sweet-smelling roses were still in bloom at summer’s end, and everything stayed greener than in Aquitaine because the sun was less fierce. The gardeners were skilled and, even enclosed as it was, the pleasance was an escape into a different, fresher world that offered respite from the machinations and backbiting of the court.

Today, the September sun cast mellow, translucent light over the grass and the trees, the latter still clad in their summer green but beginning to crisp with gold at the edges. The dew sparkled on the grass and Alienor had a sudden desire to feel the crystal coldness under her bare feet. On an impulse, she slipped off her shoes and hose and stepped on to the cool, sparkling turf. Petronella was swift to follow her example, and the other ladies, after a hesitation, joined in, even Louis’s sister Constance, who usually hung back from any kind of daring or giddy behaviour.

Alienor took several dancing steps, turning and twirling. Louis never danced. He had not been raised to such skills and delights, whereas she had. When forced, he performed each move with rigid precision, but did not find it pleasurable entertainment and could not understand why others thought it was.

Petronella had brought a ball out with her and the young women began tossing it to each other. Alienor hitched her dress through her belt. The suffocating feelings dissipated in the flurry of activity and she delighted in the vigour of the game and the feel of the cold, wet grass between her toes. The hem of her dress soaked up the dew and whipped around her bare ankles. She leaped, caught the ball against her midriff and, laughing, flung it to Gisela, who had been assigned to her household.

A shout of warning from Floreta, accompanied by a frantic hand flap, made Alienor stop and look round. Several men in clerical garb carrying stools and cushions were advancing on them along one of the paths. They were being led by an emaciated monk, who was addressing them in a raised voice as they walked. ‘For what is more against faith than to be unwilling to believe what reason cannot attain? You might consider the words of the wise man who said that he who is hasty to believe is light in mind …’ He ceased speaking and looked towards the women, an expression of surprised annoyance flitting across his face.

Alienor tensed. This was the great Bernard of Clairvaux, religious and spiritual crusader, intellectual, ascetic and tutor. He was esteemed for his holiness, but was also a man of rigid principles, unswerving in his opposition to anyone who disagreed with his views on God and the Church. Four years ago, he had disputed with her father over papal politics, and she knew just how tenacious Bernard could be. What he was doing in the garden, she did not know, and he seemed to be thinking the same of her. She was suddenly very aware that her shoes and stockings were draped over the side of the fountain and was annoyed to be caught at such a disadvantage.

She made a small curtsey to him and he responded with the slightest inclination of his head, his dark eyes full of censure.

‘Madam, the King told me that the gardens were available for me to discourse with my students this morning.’

‘The King made no mention to me, but by all means be welcome, Father,’ Alienor replied, adding with a spark of challenge: ‘Perhaps we could sit and listen for a while.’

His lips thinned. ‘If you truly wish to learn, daughter, I am willing to teach, although to hear the words of God, one must first unstopper one’s ears.’

He went to sit down on a turf seat, prim as a dowager, and his students gathered around him, pretending to ignore the women while stealing furtive, outraged glances at them.

The Abbot of Cîteaux arranged his robes, resting a skeletal hand on one knee and raising the other, holding his tutor’s rod in a light grip.

‘Now,’ he said. ‘I spoke to you earlier of faith, and we shall return to that question in a moment, but I am suddenly reminded of a letter of advice I have been writing to a most holy virgin concerning earthly pleasures.’ He cast his gaze towards Alienor and her ladies. ‘It is truly said that silk and purple and rouge and paint have their beauty. Everything of that kind that you apply to your body has its individual loveliness, but when the garment comes off, when the paint is removed, that beauty goes with it; it does not stay with the sinful flesh. I counsel you not to emulate those persons of evil disposition who seek external beauty when they have none of their own within their souls. They study to furnish themselves with the graces of fashion that they may appear beautiful in the eyes of fools. It is an unworthy thing to borrow attractiveness from the skins of animals and the work of worms. Can the jewellery of a queen compare to the flush of modesty on a true virgin’s cheek?’ His eyes bored into Alienor. ‘I see women of the world burdened – not adorned – with gold and silver. With gowns that have long trains that trail in the dust. But make no mistake, these mincing daughters of Belial will have nothing with which to clad their souls when they come to death, unless they repent of their ways!’

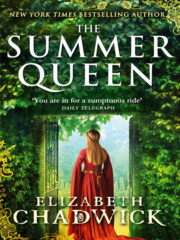

"The Summer Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Summer Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Summer Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.