They embraced.

"I will present you to my ladies," said the substitute Queen, but at that moment Joanna could sustain her role no longer.

"My son, my son," she cried, "do you not know me?"

Arthur looked in astonishment from the lady-in-waiting to the Queen.

"Yes," said Joanna, "I am your mother."

"I see it now," cried Arthur.

"I had to wait awhile," said Joanna. "My heart was too full."

They embraced warmly, then looked at each other searchingly. "You were but a boy when you went away," said Joanna.

"Oh, Mother, so much has happened since then."

"I was so proud of you, my Earl of Richmond."

"Alas, Mother."

"Henry will treat you well. I would I could keep you here with me."

"I come as a prisoner, my lady."

Joanna nodded.

"Come, tell me of home. Tell me of your brother and your sister ... She has lost her husband."

"Agincourt was disastrous for us."

"And such a victory here. They are still having their pageants and their revelries, their thanksgiving services. The bells are ringing all over the country."

"One King's victory must be another's defeat. Mother."

"And you were on the wrong side."

"It seemed so impossible that the English could triumph."

"Nothing is certain in war" said Joanna. "Now we must make the best of what is left to us. It will not be long, I feel sure."

She was right.

That day Arthur was taken back to his prison in the Tower. The brief reunion was over.

The King kept Christmas at Lambeth.

He was restive. He had won a brilliant victory at Agincourt but all it had brought him was Harfleur. He was no nearer to the crown of France than his predecessors had been.

After Agincourt it would have been the utmost folly to have marched to Paris. Wretched and defeated as it was, what was left of the French army could have stopped him. If the French were in a sad state so were the English. Many of his soldiers were suffering from dysentery. They had fought magnificently but they were in no shape to endure another battle for a while. Good general that he was he had seen there was only one thing he could do and that was return home and get together more men and more stores before he began another campaign.

He could be proud of the achievement. The French had suffered a shattering defeat and they would be demoralized. No more barrels of tennis balls would be sent by the arrogant Dauphin. It was good to contemplate what his feelings must be at this time. It was a glorious moment, there was no doubt about that, but he must not be blinded by his success.

He needed men restored to health; he needed supplies; and raising an army was a costly matter.

But Agincourt had made Englishmen proud again. They had a King whom they could admire. It was like the days of great Edward all over again. The people loved a King who was a great soldier and could bring conquests to the honour of the country and spoils of course to add to its riches.

Celebrations there must be to remind the people what he had brought them; before they were asked to provide money for more conquests they must be allowed to celebrate those which had been won. But the King was impatient. Agincourt had been a revelation. He could almost feel the crown of France on his head.

So at Christmas while he feasted and joked with his friends and danced and watched the mummers, his thoughts were of war. Plans were forming in his mind. He must go on. It would be foolish not to follow up the victory while the French were in such a low state and the English intoxicated by victory.

The new Archbishop Chicheley was growing fanatical about the Lollards and was pursuing them relentlessly. The King often thought of John Oldcastle and wondered where he was hiding himself. How much more satisfactory it would be if he were to come and fight with his King. There were few better soldiers.

If he would come back and fight with me, thought the King, all this Lollardry would be forgotten.

But John did not come. He remained in hiding, no doubt plotting. He was as fixed in his determination to uphold the Lollards as Henry was to gain the crown of France.

Henry must raise money and continue. He was wasting time here.

The people were with him. They wanted more conquests. They were looking forward to prosperity and the end of the war with France and their King firmly established on that throne.

They were living now in the euphoria of great victory. Life seemed more prosperous. It was not, but it seemed so and thought Henry with a certain amount of cynicism, one that was as good as the truth until they woke up to reality. He had ordered that the streets of Holborn be paved. This had never been done before and the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Henry Burton, had brought in improvements to the streets of London by hanging lanthorns which were kept burning throughout the night.

The people were grateful. They loved their King.

But it was the eternal cry of Money. Money to pay the soldiers, money to pay for the arrows and all the weapons of war. Money for the food they would need. Money! Money!

The King rode to Havering to see his stepmother. She greeted him with affection and he talked to her of his plans.

She listened, feigning an enthusiasm which she could not feel. Her family were on the opposing side. It was an irritation between them. How could he boast to her of the glories of Agincourt when that battle had brought disaster for so many members of her family?

The affection he had hitherto felt towards her was tinged with a mild dislike.

She had come to England as his father's second wife and grown rich here. He had heard it said that she was one of the richest women in the country, but like many rich people who had taken delight in garnering their wealth, she was rather loth to part with it.

"My son visited me here," she said.

"I know," he answered. "I gave orders that he should be allowed to do so."

"Thank you, my lord. It was good of you. Your goodness makes me venture to ask if I might see him again."

"My lady, he is a prisoner. He is your son but he is also a traitor. We cannot allow traitors to roam freely about our land. That would be folly, you must realize."

She was silent.

"I intend to carry on the war in France until I have brought it to a satisfactory conclusion," he went on. "I should be there now ... but first I have to build up stores, equipment, pay my soldiers and so much more."

"War is a costly business in treasure and more tragically in blood," said Joanna sombrely.

"So we have seen. Madam," said the King. "But my cause is just and I am determined on victory. I need money."

Her eyes strayed round the chamber. She lived well. She liked luxury. She was indeed a very rich woman.

"I am relying on those who love me and a just cause to come forward with their offerings," he said.

She nodded.

"I have always looked upon you as a friend."

"I will ask my treasurer what can be supplied," she said cautiously; she was already making plans to have the finest of her treasures placed in great chests and hidden in the vaults. "I have given much to the poor," she went on. "I am not as rich as I once was."

You lie, he thought. My God, the woman is on the side of the French. She is all ready to turn traitor, as her son was.

He took his leave shortly. He was in a resentful mood. She amassed wealth under my father, he thought, and she will not give up to me what I so desperately need.

As he rode away he said to his brother Bedford: "I do not trust the Queen."

Bedford replied: "I was talking to John Randolf her confessor. He says she is in constant private talk with those two sorcerers Colles and Brocart. He does not like them nor their influence with the Queen."

"Does he think she practises their evil arts?"

"It is strange how she has become so rich."

The King frowned. "It might be that there is some sorcery in it," he replied.

He felt a sudden surge of anger against her. She had won her wealth through dabbling in dark arts then; and she was very reluctant to part with a penny of it.

His thoughts were occupied with how he could raise money.

"When he returned to London he had decided to pawn his crown and jewels. His uncle, the Bishop of Winchester, would advance him one hundred thousand marks for them; and he would sell a part of the royal jewels to the City of London for ten thousand pounds.

In the month of July two years after the battle of Agincourt Henry was ready to sail to France again. He left with twenty-six thousand men on board a fleet of one thousand five hundred ships.

He took among other strategic places, Caen and Falaise. But the war was not yet won.

John Oldcastle with his band of faithful followers had for four years been wandering in the Welsh mountains. During the summer they lived out of doors and would sit round a camp fire when darkness fell and talk of the days when they would establish their faith throughout England and bring a better life to many poor people. With the coming of winter there must be an end to this life which had an appeal for all of them; then they must find shelter by night in any inn or wayside cottage where someone would give them a place to lie down. All the day John was trying to recruit men to his banner; but it was amazing how difficult it was to arouse enthusiasm for battle even amongst the Welsh who like the Irish and Scots were usually ready to attack the English.

He heard news of Agincourt and it pleased him to know that Henry had won renown throughout the country.

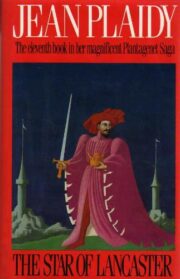

"The star of Lancaster" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The star of Lancaster". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The star of Lancaster" друзьям в соцсетях.