The first real trouble came from Wales and there he discovered a formidable enemy in a man called Owain ab Gruffydd, lord of Glyndyvrdwy or as he was becoming known throughout England, Owen Glendower.

Owen had been a student of English law at Westminster and at one time was squire to the Earl of Arundel who had estates in Wales. When Arundel took sides with Henry of Lancaster Owen was with him, although Wales in general supported Richard and there was murmuring throughout that country when Harry was created Prince of Wales.

The trouble really started when Owen quarrelled with Reginald Lord Grey of Ruthin over certain lands which they both claimed, and Owen came to Westminster for the case between them to be tried. There he was treated with a certain amount of contempt but he managed to get the case brought before the King and Parliament. "The man is bent on getting what he calls justice," the King was told. Henry impatiently waved the matter on one side. "What care we for these barefooted scrubs," he cried contemptuously. The King's words were reported to Owen who went fuming back to Wales.

Henry had made an enemy for life.

When a Scottish expedition was planned Owen should have been a member of it, but out of revenge Grey of Ruthin failed to deliver the summons until it was too late for Glen-dower to comply, and, as he did not join the expedition, Grey denounced him as a traitor. This was too much for a man like Owen to tolerate and if he could not get satisfaction at Westminster over the matter of his lands, what justice could he hope for now. He decided to take the law into his own hands. He made war against Grey, plundered his lands, killed some members of his household and declared publicly that the Welsh would never receive justice, that they were treated with contempt by the English and if any Welshman would march under his banner they would do something about it.

Henry heard the news with dismay and at first thought this was but a local rising but he was soon to learn his mistake. The Welsh were on the march. The cry was Liberty and Independence. Not only did the inhabitants of Wales rally to Owen Glendower's banner, but Welshmen in England left their homes to travel to Wales.

It was necessary to put an end to this rebellion and Henry marched in person to the Welsh border. Owen Glendower might have rallied a great force but it would not stand out long against the trained bands of English archers. There he was wrong, for Owen Glendower was too cunning to meet Henry's army in a confrontation. Instead he and his men retreated to the mountains where it was impossible to follow them. They knew every rock and crevice.

Those mountains were impassable and had defeated others before Henry. They provided the perfect stronghold. Moreover the weather was treacherous and the Welsh had their successes, the chief of which was the capture of Lord Grey and Sir Edmund Mortimer, the uncle and guardian of the young Earl of March whom so many believed had more right to the throne than Henry. It was simply not possible to bring the conflict to a speedy end. The Welsh could not be conquered as easily as that and what could have been settled by law—if Owen Glendower had been treated with justice—developed into a war which neither side could bring to a satisfactory conclusion.

Henry left a company in Wales and went to Oxford where he saw his son.

Harry had been sent to study under his uncle, Henry Beaufort, who was Chancellor of the University, but he was tired of Queen's College and chafed against his youth, therefore when he heard what his father had to say he was delighted.

Harry noticed his father had lost some of his healthy colour. Being a King had its responsibilities, that was obvious, but Henry was clearly delighted with his son's appearance. Harry had grown and he was a picture of glowing health.

When they had embraced Henry said: "I have come to talk to you very seriously, Harry. I think it is time you gave up Oxford. There is work for you to do."

Harry's eyes shone at the prospect. "Right gladly will I leave Oxford," he said. "I am no scholar, my lord, and nothing will make me one. I want to fight beside you."

"That is exactly what I want you to do, Harry." The King touched his forehead in a weary gesture. "There is so much trouble everywhere. The Welsh ... the Scots. And can we ever trust the French?"

"It is no time for me to be poring over books in college," agreed Harry.

"That is a view we share, my son. The truth is I need you. Would to God you were a little older."

"I am fifteen now. Father."

"Fifteen. God's truth, Harry, you look three years older."

Harry beamed with pleasure. "Where would you have me go?"

"To the Welsh border. Perhaps later to Scotland. You have to learn, Harry. You have to learn fast."

"Never fear, my lord. I have learned much already."

"You have to learn how to defend us. We have to hold what we have. My God, Harry, we shall have to hold on to it firmly."

"I have always known it. I shall be ready, never fear. I shall leave at once."

The King held up his hand. "Not quite so fast. Remember you are the heir to the throne. I will speak to the Chancellor. He will understand. You will have to do with what education you have. Your task now is to learn to be a soldier"

"I am ready, my lord" said Harry.

Yes, he was. And a son to be proud of. I thank God for him, thought Henry. Would he were older.

He hesitated. Should he tell Harry of the strange malady which he feared might be threatening him? He decided not. He did not want to show him the discoloration of his skin and thanked God that he could so far hide it. It came and went and when it was there a terrible lassitude came over him.

He hoped it was not some dreaded disease.

Harry must be prepared.

When Harry arrived in North Wales he was greeted by Sir Henry Percy, known as Hotspur and a man some twenty years his senior with one of the most formidable reputations in the country. He had in fact been born in the same year as those two Kings, Henry the reigning one and Richard the dead one, and his attitude towards young Harry was inclined to be paternal. A great soldier himself Hotspur recognized those qualities in Harry; but Harry had much to learn. No matter, he would learn.

Hotspur's home was in the North. His father was the great Earl of Northumberland and his family looked upon themselves as the lords of the North and of no less importance than the King. They were very much aware that it had been their power which had put Henry on the throne; and they were determined that Henry should remember it.

Harry recognized Hotspur's qualities and was ready to learn from him. This was the life for him. He was born to be a soldier. He won immediate popularity with the men, his manners were free and easy and while he retained a certain dignity he could talk with them on equal terms; he had an affability which his father lacked, yet at the same time there was in him that which suggested it would be unwise to take advantage of his nature or his youth. Hotspur recognized in him the gift of leadership; and this pleased him.

There was another man who was attracted by the character of the Prince and Harry himself could not help liking this man; consequently they would often find themselves in each other's company. They made a somewhat incongruous pair— Harry the young Prince fifteen years old and Sir John Old-castle who was thirty years his senior—the fresh young boy and the cynical old warrior had no sooner met than they were friends.

They would sit together while Sir John talked of his adventures, of which he had had many. His conversation was racy and illuminating and it gave Harry a fresh glimpse into soldiering.

"It is not all glory, my Prince," Sir John told him. "There's blood too ... plenty of it. No use being squeamish in war, my young lord. You've got to get in first and skewer the guts of your enemy before he gets yours. Always be one step ahead ... that's war. But there's another side to it." Sir John nudged Harry. "Oh yes, my little lording, there's another side to it. Spoils ... there's wine and good meat and there's something better still. Can you guess what it is? It's women."

Harry was already very interested in women and Sir John knew it.

"I can see you're another such as myself," he commented comfortably. "I couldn't get along without them ... nor will you. Well, "tis a good and noble sport ... pleasuring here and pleasuring there and always with an eye for the next one. Always on the look out. There'll be all sorts to your taste, I don't doubt. The dark and the fair ... and not forgetting the redheads. I knew a redhead once ... the best I ever knew. Warm-natured, redheads are. You'll know that one day, my lord, for you're like old John Oldcastle, you've got a warm and loving nature. And it's the sort that'll not be wasted."

Harry greatly enjoyed these conversations. They were in contrast with his association with Henry Percy. Percy was very much the great nobleman, as proud of his name as a king might be. In fact, Harry thought, Hotspur looked upon himself as a king. He expected to rule; he could endure no interference. He had once said the Northumberlands were the Kings of the North and no King of England could rule without them. If anyone failed to show the respect he considered his due. Hotspur's fury could be roused. The men went in fear of him while at the same time respecting him for the excellent leader he was.

Harry found that he could work well with Hotspur and learn from him, because in Harry there was a certain military instinct which he recognized, and so did Hotspur and Old-castle. The Prince could enjoy the company of these men and draw enlightenment from both of them. From Hotspur he learned how to conduct a campaign while Oldcastle made him see the needs of the men and to understand how to treat them.

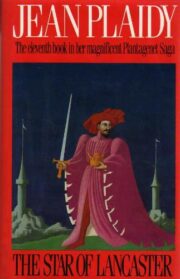

"The star of Lancaster" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The star of Lancaster". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The star of Lancaster" друзьям в соцсетях.