I am lonely here, Chère Maman, and hope for one small visit, if you…

The Chasseurs have been released toward Santo Spirito, leaving under cover of the snow flurries with…

…so I have shoes again. There was a brief encounter with the dogs that eat the dead upon the battlefield, but…

…for the 157 horses held by heavy cavalry and light horse artillery. The commissary strength is 59 pack mules in theory, but of these, at least a third will founder if we are forced to retreat as seems…

I am feeding one of the cats that lives in the ruins of the innyard. It has white patches…

Paper curled in her fists. Her hands shook.

Grey said nothing and did not try to stop her. She could destroy every file in this room, and Grey would not stop her. None of it, none of it, made the least difference.

The fools had left cup, plate, saucer upon the table. They exploded, one after the other one, when she threw them upon the floor. They were not so smart, these English.

“I hope they were expensive dishes.” She looked at the pieces and the crumbs and the spots of coffee all across the rug and the spoon lying on its side. Her head ached horribly.

“Very expensive. Crown Derby.”

“I would feel better if I killed someone. I am almost sure of it. You are stupid to leave knives all over this room.” She had held her hand back from murder for her whole life, but it was never too late to start. “After I finished stabbing you, I could burn this house down. It would not be so hard. I could burn all your thousands of files you love so passionately.”

“Start with these.” He pointed at the limp, desolate heaps of paper on the floor. “I’ll help.”

She would not cry again. Probably she would never cry again in all her life. She wanted to hold Grey and fall to pieces in his arms like a weakling, but assuredly, she also wished to kill him.

The hearthrug had a hundred little holes in it where sparks had fallen for many years. “My father was a great man.”

“A very great man,” Grey said. “We argued about him at Harrow, in the common room at night. What he wrote. What he and the others did in Lyon. I was halfway a Revolutionary from reading him.”

Beside her was one of those strong, heavy chairs in which the room abounded. It was old and worn from spies sitting upon it. For Grey and the others, this was their refuge, their place to talk and read and forget their work. The heart of the house. These wise and terrible men had brought her here so she would be enclosed in their concern, in their most sheltered place, while they destroyed her.

She swallowed. “It is hard to believe my father was an English.”

“Welsh.”

“Do not nitpick at me. It is a difference only an English would notice, as trout are enthralled by the difference between a trout and a pickerel.”

The fire on the hearth was newly lit. They had built a fire to comfort her because they had no other help to offer. They knew she would be cold. When one’s heart is ripped entirely from the body, it leaves one quite cold.

She wrapped her arms around herself, but it was not like being held by Grey. “I was taken by Russians, once, when I was fourteen.” Talking cut like knives in her throat, but it hurt less than staying silent. “I had been betrayed, as one often is. They knew my name. One of them, when he heard it, knew whose daughter I was. All of them, all of the officers, had read Papa’s books and knew how he died. And they let me go. The interrogators had barely started on me. I was not even scarred.”

Grey was stiff with his anger at those long-ago Russians. “No scars. How nice.” He could be sarcastic sometimes.

“My life was spared, in lands far from France, because men knew my father’s name.”

He had decided she was safe to approach again. He came behind her and put his hands on her shoulders. It was warm, being held. “Your father was a brave man.”

“I was there, do you know. The day of the march. They carried no weapons. Not a pocketknife. The loom workers who were starving walked to the town hall to face men with guns, knowing that some of them might die. They asked only for the honest wage. Only that. Every French schoolboy knows the names of those who were hanged.” The lump of ice that was her stomach began to melt. “I have always been proud to be his daughter.” That had not changed. The most important truths had not changed. “He did not make that march because he was a spy for England. He did it for those men. He loved France and died for her. “

“He was a man capable of loving more than one nation.”

“My father would not have lied to me. If he had lived till I was old enough to talk with, he would not have lied to me.”

“Your father would have sent you to England when things went bad in France. Before the Revolution. You’d have been safe in a girls’ school in Bath.” He let that sink in. She would have been a schoolgirl in some provincial town. That would have been her life. It was a thought to chill the blood.

Grey knew her. He had taken her to his bed, and held her while she was vilely sick, and walked with her all the long road from the coast. He knew exactly what he said to her.

“I would not have liked a school in Bath. You are being subtle with me, and I wish you would stop. I am disgusted with cleverness. I am drowning in it.”

Wind played with the curtains and slipped under papers all over the floor, making them lift and settle like birds getting ready to sleep. One paper turned over altogether. One of her so-many letters. She had written, always, by every courier, when she was off spying. Because Maman worried. She had believed, right to her soul, that Maman worried about her.

He saw where she was looking. “Have you asked yourself why your mother lied to you?”

“To make me her puppet. To use me. You have never seen me in the field, Monsieur Spymaster. I am useful beyond measure.”

“You’re not a child, Annique. Stop acting like one. She could have told you the truth and still used you. You’d have done whatever she asked of you.”

“I do not want to hear this.”

He went on relentlessly. “She didn’t have to lie to you. She could have told you the truth when you were eight. You’d have been even more useful to her. Think about it. Why did she lie?”

“I hate you.” That, at least, required no thinking. That, she could have done in her sleep.

“She lied to you, so you didn’t have to lie. She gave you René Didier and the house in the Quartier Latin. She gave you learning to cook in Françoise Gaudier’s kitchen. She gave you being one of Vauban’s people. She gave you those years.”

She closed her eyes. Grey made no demands, not even that she speak. It was possible to stand and absorb these thoughts and consider what her life would have been if Maman had told her the truth.

She had seen clever ceramics from Dresden, painted and glazed to look like apples and lettuces and cauliflowers. Wholesome and edible to the eye, cold as skeletons to touch. She would have been like that, if she had grown up playing a double role.

“Maman was wise,” she whispered at last, “and very alone. I had not realized how alone.” She looked around the room. “I should pick up the papers.”

“Leave it for Adrian to clean up. He wants to slay dragons for you. Come downstairs.”

“No. Take me to your bed. I need you.”

Thirty-three

IN THE DEEP OF NIGHT, SHE DREAMED.

The prison courtyard was dark, full of bobbing lanterns and loud voices. She could not get to Papa. He was in the wagon with the other men. They grabbed at Papa. Shoved him.

“It’s the little girl,” someone said.

“Dieu. Get her out of here.”

It was not right. Papa should not look like that. Jerking like a fish on a string. Kicking and swinging. His face was…ugly. Not like Papa. Black and ugly with his mouth open.

They tried to grab her. Darkness around her and stone walls. She ran and ran, back the way she had come, into the prison. “Maman. Maman. Où es-tu?”

In the long corridors of the cells, she heard screams. Thin, high screams like a pig being killed. Soldiers were everywhere with their high leather boots and their guns. She clawed her way through. In the middle, Maman was on the floor. She was naked. There was red blood on her mouth.

The man had pulled his breeches down. White, hairy thighs showed under his jacket. He was hurting her. Making her cry.

She would make them stop. “Arrêtez. Arrêtez. Maman. Maman.”

Someone picked her up. She could see nothing but the blue coat with brass buttons while he carried her away.

“Maman…”

She woke in bed, sweating and cold.

Grey held her. “It’s a dream. It’s only a dream. Go back to sleep.” He spoke French and pulled the blanket over both of them.

She shivered. “She found them later. The men who hurt Papa.” She was only half awake. She put her arms around Grey, slipping back into sleep. “She told me once. The judges and the soldiers from Lyon. The men who killed Papa. During the Terror she found them, and they died for it. Every one.”

Thirty-four

GALBA COUNTED ELEVEN CHIMES FROM THE clock in the front parlor. Another hour had passed. Still no sign of Robert and the others.

There were no clocks in the study. This was one of the places they occasionally kept prisoners and contained no glass, no sharp points, no wire and springs, nothing that could be made into a weapon. Even the plumed and bannered army of chessmen, Venetian and very old, was papier-mâché.

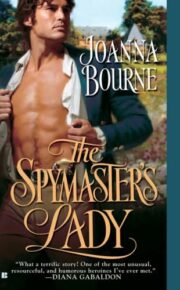

"The Spymaster’s Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.