“I am Welsh. It is like saying I am a giraffe or a teapot or an Algonquin Indian. I have become impossible and ridiculous.”

Galba stood waiting, as still as a tree that had been planted there.

“You need to know the rest.” Grey walked to the table and slid the files there toward her, in a pile. They had wide red bands across, which no doubt meant something. “I saw this for the first time yesterday. I didn’t know before.”

The file on top was labeled with many aliases, some she recognized. Among them were Pierre Lalumière and Jean-Pierre Jauneau, but the first name written was Peter Jones.

Peter Jones…Son of Katherine and Owen Jones…Cambridge University…Recruited into Service…Assigned to Brittany surveillance…Grade 7…Commendation and promotion…Assigned to Nimes…Chief of Station, Lyon…Detached Agent status…Commendation…Grade 11…Commendation…Commendation and promotion (posthumous)…

This was the file of an agent of the British Service who had been born Peter Jones and had taken the name of Pierre Lalumière. He had been a detached agent and a grade 17 when he died. His pension was assigned to his widow, Lucille Jones.

The file held hundreds of pages, old papers with their feel and smell entirely authentic. This was political reporting he had made upon the abuses of the Old Regime and on the intellectual ferment that became the Revolution. The secret societies. The political clubs. She leafed through. Pierre Lalumière, who was so honored in France that every schoolboy knew his name, had been a British and a spy.

The folder below was her mother’s. She picked it up, finding it thick.

Lucille Alicia Griffith…daughter of Anne and Anson Griffith. Born Aberdare, Wales…Recruited into Service….

Pages and pages. Maman’s political reporting from Paris. Secrets of the Austrians and Russians from Vienna. Details that were the most deep secrets of Fouché’s Secret Police.

The oldest part, deep at the back of the folder, in her mother’s tight, spare writing, was the long, dreadful story of the time of the Terror. Notes on top, in another hand, said that Maman had pulled more than three hundred men and women from the machinery of the Revolutionary Council. So many lives saved. Innocents and not so innocent, but none deserving extinction. Annique had not known her mother had done this.

The death of Lucille Alicia Jones was entered on the left-hand side of the folder in ink fresh and unfaded. She had been a grade 20 when she died, on detached service. Her pension was assigned to her daughter, Anne Katherine Jones.

She did not want to look at the last folder. Her own. It was very thick indeed. All the letters she had written to Maman, all her reports, her whole lifetime of spying, was in it.

She had laid so many secrets in her mother’s lap and never asked where they went. Now she knew. The French got only the dregs. The best had gone to the British. It had always been the British, all those years.

“You’re convinced this isn’t fake,” Grey said, when she stopped and closed the file and sat unmoving over it.

“It is genuine.” She stared at a book lying on the shelf. If someone had asked her what it was, she could not have told them the word for it. “Maman was remarkable. There is no French agent so deeply planted within the British. She had access everywhere, my mother.”

“She was unique,” Galba said.

“Even Vauban. All those years I was with him, I told her everything we did. Now I see it written in this file. I was so clever and pleased with myself, and I gave everything to her. René, Pascal, Françoise…and Soulier. Soulier, who trusted me with such messages…I betrayed them all. Vauban would spit upon me for being so stupid.”

Then she could speak no more. It was hard to see because of the water in her eyes. If she once started crying, it would pierce like icicles.

Grey took the files out of her hands and made her stand up and pulled her to hide against his chest. She did begin crying then. It hurt just as much as she had thought it would.

There were many times in the past it would have been perfectly simple to be killed. If she had been sensible, she would have died then and never come to England to this room to see everything of importance shatter to bits.

She had many tears in her, but at last she pushed away from Grey and dried her face upon her forearm, clumsily and quickly, like a child. It was time for her to think and not just hurt. Although she would continue to hurt as well, probably forever.

“I am curious.” It was a crow’s squawk. “I am curious to see what you will do with me now that I am made nothing in this way. In one hour, you have destroyed me. I have been a traitor all my life. All my life, everything I did…It was for nothing. Nothing.”

Grey slid a plate across the table toward her. “Annique, eat something.”

She did not move.

“If nothing matters,” he said, “it doesn’t matter if you eat.”

It was coffee and rolls. He was right, of course. None of it mattered. She put her elbows on the table to steady herself and drank coffee and then ate most of a roll so her capitulation would be complete. When she was finished, she put her head into her hands.

The floor creaked as Galba moved. “Annique…” He had to repeat it before she looked up. “Annique, I am in some part the author of this injustice. I did not intervene. I am profoundly sorry.”

Which was English too complicated for her. “I am the offspring of a mermaid and a sea cod. And they were married. I had no idea. Why did my mother lie to me?”

“At first you were too young to burden with this secret. Later…” Galba spread his hands. “There is no excuse. Later, she chose to keep it from you. The last time I saw her, you were twelve. We argued about this, fiercely. She told me you were a child of single heart and she would not tear you in half. I don’t think she expected either of you to survive this war. Grey, she’s not even hearing me.”

“Leave her here with me. She needs time.”

“Do not talk about me as if I am not here.” But she had become insubstantial as smoke. If she was not French, she could not imagine what she might be. Maybe nothing.

“I apologize.” Galba sighed. “Annique, you are not the offspring of a halibut and a mythical sea creature. Your parents were two of the finest people I have ever known. Your mother had great respect for you. She knew someday we might sit in this house and face this moment.”

He waited for something.

“She doesn’t know.” Grey took her face between his hands, so she had to look at him, and spoke slowly. “We have to tell her. Galba’s name is Anson Griffith. If you were more familiar with the Service, you’d know that.” He waited. “He was Lucille Griffith’s father. Your mother’s father.”

Her mind was flat and barren as a tidal beach. None of the words made any sense. Maybe she had forgotten how to speak English.

Galba grunted. “When she can think again, bring her downstairs. She shouldn’t be alone.”

Grey stroked her hair, slipping it through his fingers. “She’ll be fine in a few minutes.”

“I will never be fine again.”

“Yes, you will, my little halibut. You’re incredibly tough, did you know that?”

Thirty-two

SHE COULD NOT GUESS HOW MUCH TIME PASSED. She did not hear Galba go out. When she looked up again, she was alone with Grey.

He stood by the window, lifting the curtain with the back of his fingers to stare into the street. She made some sound or changed her breathing, and he turned toward her. She saw then what was in his eyes. He would have rolled England up by the corners and moved it to Greenland, if that would have helped. He would have done that for her.

She had become pitiable. She had never been the clever Fox Cub. She had been the dog to fetch secrets to Maman. She had felt so smug in her cleverness all those years, but she had always been the dupe. All her life, the dupe.

Blood beat like drums within her ears. The world pulsed red at the edges. “Lies.” The chair scraped behind her and toppled and crashed as she pushed it aside. She pounded her fists down. “Lies and lies and lies!”

Her mother’s file lay on the table. She took it with both hands and threw it across the room. Papers disgorged in midair and flapped and scattered. “Nothing but lies!” She swept her father’s file from the table with the back of her hand. It spread out in a long, smooth line across the rug—pages and pages of his upright, precise writing.

That left her file. She ripped the cover in half. Everything emptied out across the table. Reports that should have gone to Paris. Her letters. The letters she had written Maman. Dieu. The silly, loving, trusting words she had written…all her little secrets. Everyone here had read them.

Dozens and dozens and dozens of letters, written in little minutes on the edge of battlefields, creased from being carried next to her skin. Paper dirty because she had scavenged it from the garbage, paper stolen from the officers’ tents, paper bought when she had no money for food. All those letters filled with the careful, rounded script of an obedient child.

She grabbed them and tore again and again and again till they fell out of her hands, between her fingers, small, small pieces that fluttered like leaves. Scraps fell with lines of writing turned in every direction. And she knew every word. That was the pain of it. She knew them all. With each falling scrap, in a little flash, she remembered where she had been when she wrote it.

…moved the gun emplacements to Liège. Twelve eighteen-pounders and thirty of the lesser kind, the sixand four-pounders. They are short of ammunition for the greater guns. I counted…

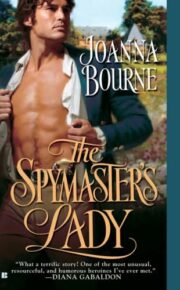

"The Spymaster’s Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.