She could picture it, that huge old farmhouse with the horses in the stable and the chickens his mother was proud of, who each had names and were of a special breed from Constantinople and not at all like other chickens. Robert had, she knew now, a house of his own called Tydings where an aunt looked after him, and another brother in the army and three other sisters, younger than he was, but married, who did not live at home.

It was a joy and a burden to know all this. She would remember it when they parted and it would make her infinitely sad.

They were encamped far back from the road, deep in the stubble of harvested fields. She turned the embers with a pointed stick. She had built such clean, invisible fires a thousand times. There was little smoke. No sparks flew into the night to show where they were.

Robert finished with his pampering of Harding and came to sit beside the fire with her. “That’s a pretty tune. What is it?”

“What? Oh. I had not realized I was humming. It is a children’s song.” She sat back on her heels. “Let me think…In English it would go, ‘Let the gutters flow with the blood of the aristocrats. Let us wash our hands in their entrails. Let all who stand against the voice of the people perish like rats.’ There is much more of it.”

“Good God.”

“Most exactly. It is a pretty tune, though. It is sad that my voice is like a jackdaw, as many people have told me. We used to sing that one, jumping rope. ‘The fat aristos shall perish, one and two. The traitors shall die, three, four.’ We were all without exception bloodthirsty when I was six. That was the year we took the Bastille. It is strange to know all those boys I played with are in the army now, or dead.”

“An interesting time.”

“It was to stand at the pivot of history, to be in Paris in those days. Dreams were as solid as the stones of the street. A thousand possibilities. That is what you English do not understand. We French will not stop until the whole world is conquered for the Revolution. Napoleon puts his harness upon those dreams and drives them for his own purposes. You do not know at all what you are up against.”

“You think the peace won’t last?”

She knew the peace would not last. The Albion plans set a date for the invasion. She knew the very road troops of the Grande Armée would march upon. Some of them, a third part of the army, would murder and pillage their way down this one. “It is Napoleon’s passion to conquer, not to rule. There will be no peace.” The fire made a comfortable hiss and sputter as she flipped ember after ember. She had seen houses and villages burned till they were just this. Embers. “He prepares again for war, even as we sit here.”

“Maybe he’ll pick some other country to invade, one with less water around it and a smaller navy.”

“And a better climate.” It had rained upon them today for a time. And yesterday as well. She did not like to be wet so continually.

“One of those Roman writers said something about the rain in England. Deformed by rain…something like that.” It had surprised her at first that Robert Fordham, smuggler and yeoman’s son from Somerset, should have the education he did. Perhaps he read much when he was at sea.

“That is Tacitus. He said the sky in this country is deformed by clouds and frequent rains, but the cold is never extremely rigorous. I do not suppose matters have changed much in a thousand years. Certainly there is still rain.”

He had taken off his black sweater to groom the horse Harding and unbuttoned his shirt far down his chest and rolled up his sleeves over his forearms. He was brown, as men become who work upon the sea, with a roughness of skin from wind and salt water. In the dim yellow light of the fire, he was a dark and massive form, with the strongness of rocks and tree trunks, uncompromising and very beautiful.

Once she could have admired him, or admired the strength of his horse, and it would have been the same. She had still possessed innocence of a sort. Her time with Grey had made her wiser and infinitely more foolish. Now when she looked upon Robert Fordham, she brooded and yearned like a schoolgirl and felt the most shameful heatedness inside her.

She did not make herself turn away and gaze upon something that would disturb her less. She had become weak.

The fire developed nicely. Soon it would be useful to cook upon. “It is not right that we French should invade here.” She glanced across at Robert. “Oh, you smile, but that is not obvious if one is French. Of a certainty, you English would be better off without your foolish German princelings who spend so much public money. You should have a republic and voting by everyone.”

“Is that what Napoleon would bring us?” Robert said softly.

“That is how it would begin.” Her life would be simpler if she did not think so much. “Napoleon would make some things better here. But at a great cost. When he comes to this green island, he will burn all those pretty farmhouses we passed today.”

“You can’t stop it, Annique.”

But she could. It was her choice whether those farmhouses would burn and the plump farm women and the barefooted children burn with them. It had become her decision when Vauban set the Albion plans into her hands in that inn parlor in Bruges, six months ago.

If she betrayed the Albion plans to England, she would be a traitor. She would die for it. Vauban would be pulled from his bed to go to disgrace and death upon the guillotine. And France would be at great peril from the detailed knowledge she gave to the British. But the children in that white farmhouse would live.

Or perhaps not. She could not know. Perhaps different children, equally innocent, would die instead. This meddling in the fate of nations was a grim affair.

Even a year ago, she would have gone to London, to Soulier, and laid everything in his lap and followed his orders. But she was not a child anymore, and her answer could not be that simple.

She turned a small square coal of glowing orange over carefully on its side, giving it most considered attention and accomplishing no purpose whatsoever. She need not decide today, after all.

Robert searched into the basket he had acquired an hour ago from that very farmhouse down the road. Under the red flowered cloth that was tucked across, it contained the most lovely things—sausages and bread and small brown eggs. This was one more thing she did not know how to deal with.

She watched him investigate. “I would not have dared to ask for these foods. You are very courageous, did you know.”

“Braving the dread Kent farmer in his lair?” He spread the cloth between them. “They’re not so dangerous.”

“He might have set his dogs upon you. Me, I do not like dogs.”

“I’ll remember that.”

The hairs of his chest were gold where the firelight struck them. She imagined how it would be if she reached across to his shirt and opened the last buttons and drew it off of him. She could almost see herself doing this.

He would feel furry, with those hairs, but his skin would be of the toughness of leather. Grey had worn a leather coat. He had wrapped it about her, keeping her warm as she wandered in and out of the drug. If she lay her cheek upon Robert, he would feel like that leather, with softness that went no farther than the outermost glide across his skin. He would be hard muscle underneath, as Grey was. His hands would be like Grey’s hands, too, rough from the work he did, only great carefulness making them soft upon her. If he put his hands upon her breasts…

She closed her eyes. Her body clenched immodestly and moistened. She did not know whether she was desiring Grey or desiring Robert. She was most probably going mad.

“Bread. Sausages.” Robert took bread from the basket as he named it and laid it on the red cloth. The sausages he skewered on a forked stick. “I’ve had enough hedge berries and sour apples. It’s no life for a man.”

“Bien sûr. But you have paid that farmer. I do not have the money to buy such a meal, having only three pounds—”

“And sixpence. Yes, you told me. I have a good bit more than that.”

“You are to be felicitated. But I cannot take this food and not pay my share. And I cannot pay my share.”

“You face moral qualms.”

“They are everywhere if one goes looking for them. Though perhaps I am being silly.”

“Sounds like it to me. And eggs.” The eggs were in the bottom, in the nest of straw the farmer’s wife had made for them. “There was a man who could tell eggs apart. At Delphos.”

He was trying to distract her. He would discover that did not work. “The story is from Montaigne. It goes, ‘He never mistook one for another, and having many hens, could tell which had laid it.’ I am not sure I believe that. But then, I do not know any hens with such intimacy. Montaigne does not help me to know what to do about this food, though he was very wise, of course. I have already taken whelks from you. I am not accustomed to being fed by strange men.”

“Do you think I’m trying to seduce you with boiled eggs?” He picked one and offered it to her, holding it up in three fingers.

“Do not be the fool.” She suddenly felt very cross. She took the egg from him, and his fingers did not touch hers, not one tiniest bit. She could have been a cloud of vapor for all the interest he took. “You are not in the least trying to seduce me, you.”

“No.” He smiled. He was perfectly friendly, and he did not desire her in the least. It was a great annoyance. “Lovely Annique, if you were camped out here with your Gypsies…” She had told him that part of her life, since he had told her about growing up on his farm in Somerset. “…would you sneak over to that nice farmer’s henhouse and steal some of his eggs tonight?”

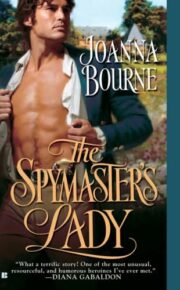

"The Spymaster’s Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.